Fossils of a small ocean animal that passed on the greater part of its body a long time ago might urge a science course book revision of how minds developed.

The main itemized portrayal of Cardiodictyon catenulum, a twisted animal saved in rocks in China’s southern Yunnan region, is given in a review published in Science by Nicholas Strausfeld, an official teacher in the College of Arizona Branch of Neuroscience, and Plain Hirth, a peruser of developmental neuroscience at Lord’s School London.Estimating scarcely a portion of an inch (under 1.5 centimeters) long and first found in 1984, the fossil had a vital mystery as of recently: a gently saved sensory system, including a mind.

“As far as anyone is concerned, this is the most seasoned fossilized mind we are aware of, up to this point,” Strausfeld said.

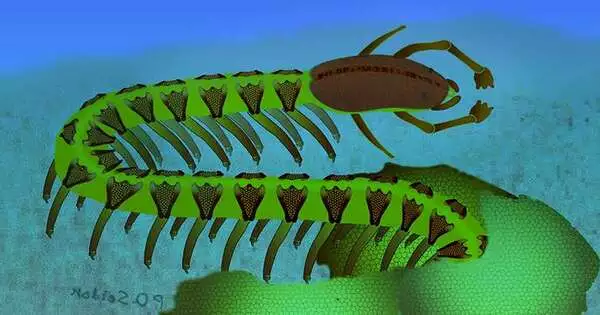

Cardiodictyon had a place with a wiped-out gathering of creatures known as shielded lobopodians, which were plentiful right on time during a period known as the Cambrian, when basically all significant creature heredities showed up throughout a very brief time frame quite a while back. Lobopodians probably moved about on the ocean floor utilizing various sets of delicate, squat legs that came up short on joints compared to their relatives, the euarthropods, which is Greek for “genuine jointed foot.” The present nearest living family members of lobopodians are velvet worms, which live mostly in Australia, New Zealand, and South America.

“Biologists saw the obviously segmented form of arthropod trunks in the 1880s and extrapolated it to the head. Assuming the head is an anterior extension of a segmented trunk, this is how the field came.”

Frank Hirth, a reader of evolutionary neuroscience at King’s College London

A discussion returning to the 1800s

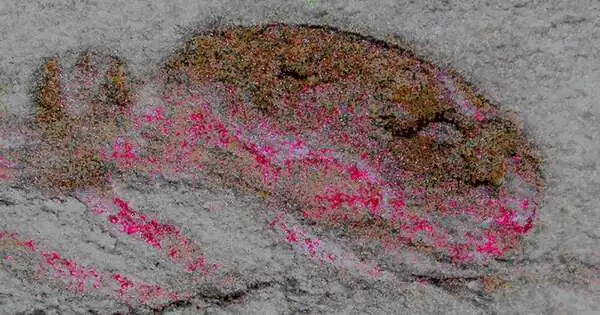

Cardiodictyon fossils reveal a creature with a divided trunk and rehashing plans of brain structures known as ganglia.This difference is obviously in its head and mind, the two of which come up short on proof of division.

“This life system was totally startling on the grounds that the heads and minds of current arthropods and a portion of their fossilized precursors have for nearly 100 years been viewed as divided,” Strausfeld said.

The tracking down, according to the creators, settles a long and warmed debate about the beginning and piece of the head in arthropods, the world’s most species-rich gathering in the set of all animals.Arthropods incorporate bugs, shellfish, insects, and different 8-legged creatures, in addition to a few different heredities like millipedes and centipedes.

“From the 1880s, scholars noticed the plainly divided appearance of the storage compartment common for arthropods and essentially extrapolated that to the head,” Hirth said. “That is the way the field showed up, assuming the head is a front expansion of a divided trunk.”

“However, Cardiodictyon demonstrates that the early head was not divided, nor was its mind, implying that the cerebrum and the storage compartment sensory system advanced independently,” Strausfeld said.

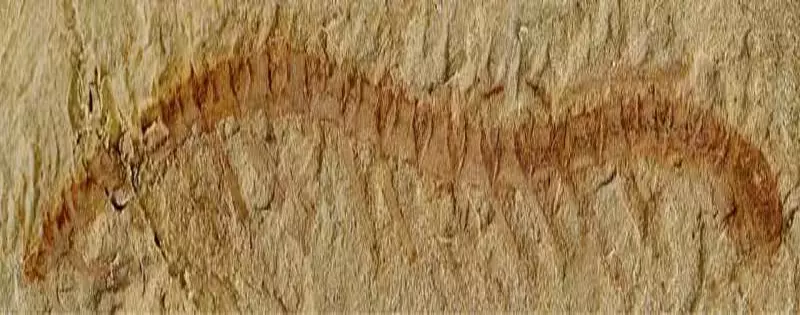

The fossilized Cardiodictyon catenulum was found in 1984 among a different gathering of wiped-out animals known as the Chengjian fauna in Yunnan, China. In this photograph, the creature’s head is to one side.

Minds truly do fossilize.

Cardiodictyon was important for the Chengjiang fauna, a popular fossil store discovered by scientist Xianguang Hou in the Yunnan Region.The delicate, fragile groups of lobopodians have preserved well in the fossil record, yet other than Cardiodictyon, none have been examined for their heads and minds, perhaps on the grounds that lobopodians are by and large small. The most noticeable pieces of Cardiodictyon were a progression of three-sided, saddle-molded structures that characterized each section and filled in as connection focuses for sets of legs. Those had been found in much more seasoned rocks tracing all the way back to the Cambrian.

“That lets us know that shielded lobopodians could have been the earliest arthropods,” Strausfeld said, originating before even trilobites, a famous and various gathering of marine arthropods that went extinct a long time ago.

“Until recently, the normal comprehension was that minds don’t fossilize,” Hirth said. “In any case, you wouldn’t expect to find a fossil with a saved mind.”Second, this creature is so small that you wouldn’t even consider seeing it in order to find a mind.”

Nonetheless, work throughout recent years, a lot of it done by Strausfeld, has recognized a few instances of saved minds in various fossilized arthropods.

A typical hereditary ground plan for making a mind

In their new review, the creators recognized the mind of Cardiodictyon as well as contrasted it with that of known fossils and living arthropods, including bugs and centipedes. Combining detailed physical examinations of lobopodian fossils with examinations of quality articulation designs in their living relatives, they conclude that a common plan of mind association has been maintained from the Cambrian to the present.

“By looking at known quality articulation designs in living species,” Hirth said, “we recognized a typical mark of all minds and how they are framed.”

In cardiodizyon, three mind spaces are each related by a trademark set of head limbs and by one of the three pieces of the front stomach-related framework.

“We discovered that each mind space and its associated highlights are indicated by similar mix qualities, regardless of the species examined,” Hirth added. “This proposed a typical hereditary ground plan for making a mind.”

Cardiodictyon catenulum fossilized head (front is to one side).The red-hued stores mark fossilized mental structures.

Examples of vertebrate mind development

Hirth and Strausfeld say the standards depicted in their concentrate likely apply to different animals beyond arthropods and their close family members. This has significant ramifications when contrasting the sensory systems of arthropods and those of vertebrates, which show a comparable design in which the forebrain and midbrain are hereditarily and formatively unmistakable from the spinal line, they said.

Strausfeld said their discoveries likewise offer a message of coherence when the planet is changing decisively due to climatic movements.

“At a time when major land and climatic events were reshaping the planet, basic marine creatures, for example, Cardiodictyon, gave rise to the world’s most diverse gathering of organic entities—the euarthropods—that eventually spread to every new territory on the planet, yet are now being undermined by our own fleeting species.”

The paper, “The Lower Cambrian Lobopodian Cardiodictyon Resolves the Beginning of Euarthropod Minds,” was co-written by Xianguang Hou at the Yunnan Key Lab for Fossil Science in Yunnan College in Kunming, China, and Marcel Sayre, who has arrangements at Lund College in Lund, Sweden, and at the Branch of Organic Sciences at Macquarie College in Sydney.

More information: Nicholas J. Strausfeld et al, The lower Cambrian lobopodian Cardiodictyon resolves the origin of euarthropod brains, Science (2022). DOI: 10.1126/science.abn6264. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abn6264

Derek E. G. Briggs et al, Putting heads together, Science (2022). DOI: 10.1126/science.add7372

Journal information: Science