Researchers have finally solved a centuries-old puzzle in the evolution of life on Earth, revealing what the primary creatures to make skeletons appeared to be.This revelation was conceivable because of an especially well-saved assortment of fossils found in eastern Yunnan Province, China. The aftereffects of the exploration were distributed on November 2 in the logical diary, Procedures of the Regal Society B.

The main creatures to fabricate hard and strong skeletons appeared unexpectedly in the fossil record in a landsquint of an eye during an event known as the Cambrian Blast around a long time ago.Large numbers of these early fossils are basic, empty cylinders, ranging in size from a couple of millimeters to numerous centimeters. However, it is unknown what kind of creatures created these skeletons because they require protection of the delicate parts required to recognize them as having a place with significant gatherings of creatures that are still alive today.

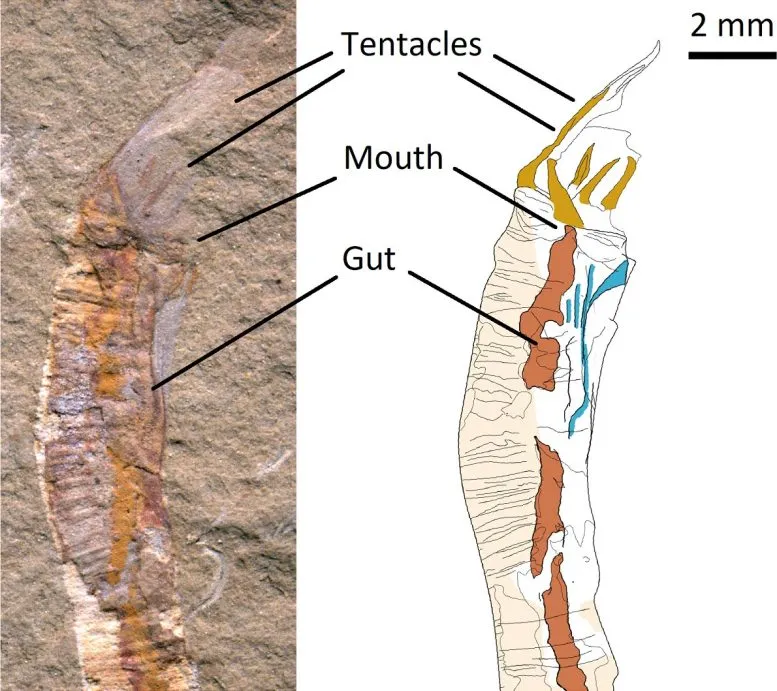

Fossil example (left) and chart (right) of Gangtoucunia aspera saving delicate tissues, including the stomach and arm.

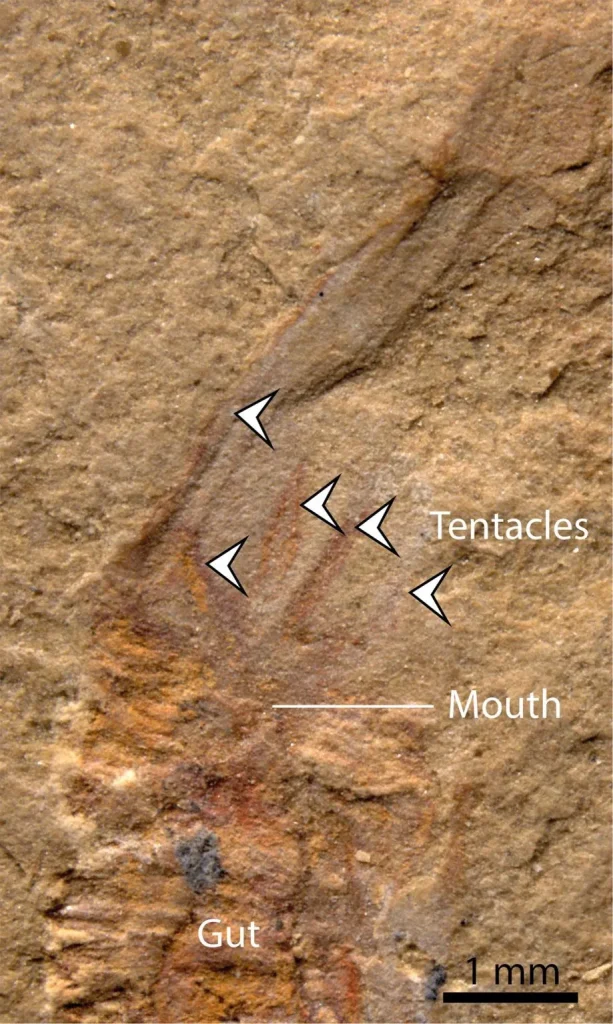

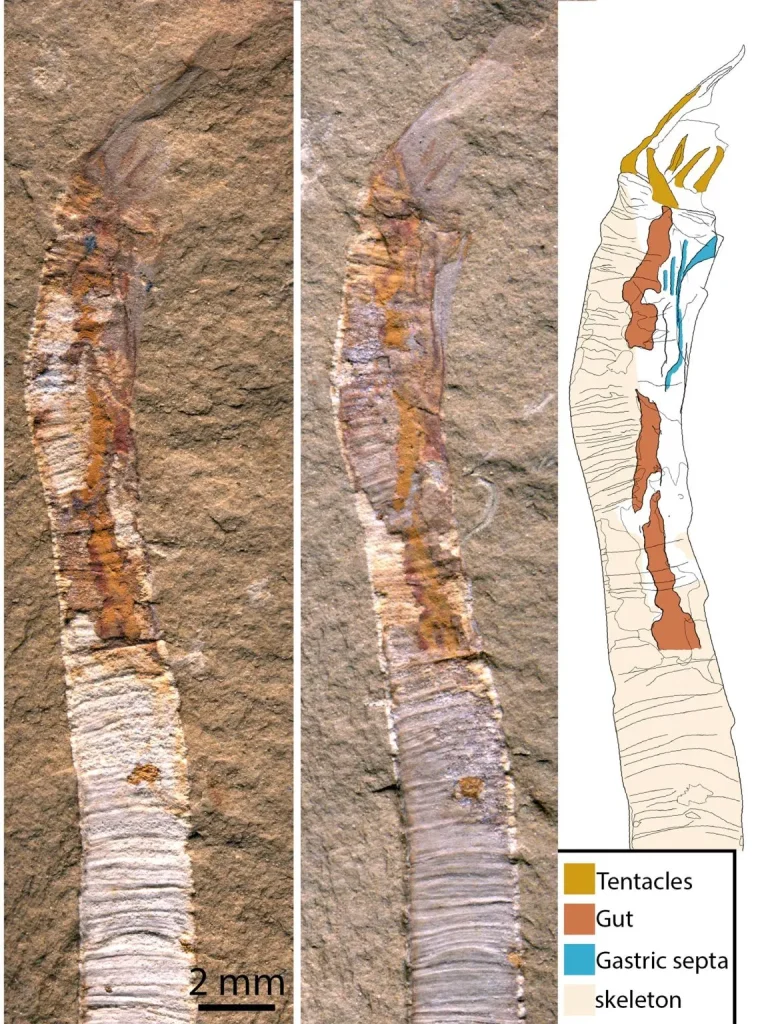

Four examples of Gangtoucunia aspera with delicate tissues still flawless, including the stomach and mouthparts, are remembered for the new assortment of 514 million-year-old fossils. These reveal that this species had a mouth bordered with a ring of smooth, unbranched limbs around 5 mm (0.2 inches) long. Almost certainly, these were accustomed to stinging and catching prey, like little arthropods. The fossils likewise show that Gangtoucunia had a visually impaired, finished stomach (open just toward one side), divided into inner pits that filled the length of the cylinder.

“This is truly a once-in-a-million find.” These mystery tubes are frequently found in groups of hundreds of individuals, but they were previously classed as ‘difficult’ fossils because there was no way to describe them. A critical piece of the evolutionary puzzle has been firmly placed as a result of these amazing new examples.”

Dr. Luke Parry, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford,

These are highlights seen today just in current jellyfish, anemones, and their direct relatives (known as cnidarians), creatures whose delicate parts are very uncommon in the fossil record. The review shows that these basic creatures were among the first to develop the hard skeletons that make such a big deal about the known fossil record.

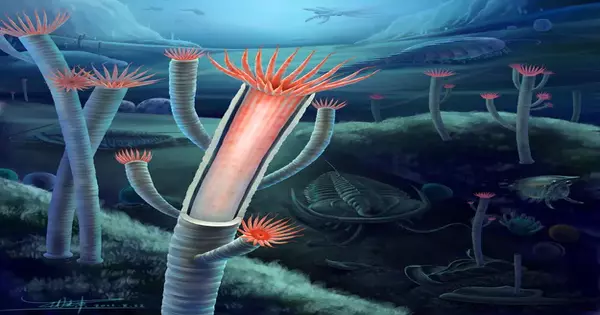

As per the scientists, Gangtoucunia would have seemed to be like current scyphozoan jellyfish polyps, with a hard, rounded structure moored to the basic substrate. The arm and mouth would have reached out externally from the cylinder, yet might have been withdrawn inside the cylinder to stay away from hunters. In contrast to living jellyfish polyps, in any case, the container of Gangtoucunia was made of calcium phosphate, a hard mineral that makes up our own teeth and bones. Utilization of this material to assemble skeletons has become more uncommon among creatures over the long run.

A close-up photo of the mouth area of Gangtoucunia aspera shows the arms that would have been utilized to catch prey.

Relating creator Dr. Luke Repel, Branch of Studies of the Planet, College of Oxford, said: “This truly is a one-in-a-million disclosure.” These strange cylinders are often tracked down in gatherings of many people, yet, as of recently, they have been viewed as “risky” fossils since we had no chance of grouping them. “Because of these uncommon new examples, a vital piece of the developmental puzzle has been set up solidly.”

The new examples plainly show that Gangtoucunia was not connected with annelid worms (night crawlers, polychaetes, and their family members) as had been recently proposed for comparable fossils. Clear Gangtoucunia bodies currently have a smooth outside and a stomach divided longitudinally, whereas annelids have sectioned bodies with cross-over parceling of the body.

The fossil was found at a site in the Gaoloufang segment in Kunming, eastern Yunnan Region, China. Here, anaerobic (oxygen-poor) conditions limit the presence of microbes that regularly degrade delicate tissues in fossils.

Gangtoucunia aspera fossil example preserving delicate tissues such as the stomach and arms (left and center).The drawing at right shows the apparent physical elements in the fossil examples.

PhD understudy Guangxu Zhang, who gathered and found the examples, said: “Whenever I first found the pink delicate tissue on top of a Gangtoucunia tube, I was shocked and befuddled about what they were. In the next month, I found three additional examples of delicate tissue protection, which was extremely thrilling and made me reexamine my liking of Gangtoucunia. “The delicate tissue of Gangtoucunia, especially the limbs, reveals that it is surely not a priapulid-like worm as past examinations proposed, yet more like a coral, and afterward I understood that it is a cnidarian.”

Although the fossil clearly shows that Gangtoucunia was a primitive jellyfish, it does not rule out the possibility that other early cylinder fossil species looked completely different.From Cambrian rocks in the Yunnan area, the exploration group has recently found very well-preserved tube fossils that could be recognized as priapulids (marine worms), lobopodians (worms with matched legs, firmly connected with arthropods today), and annelids.

Co-relating creator Xiaoya Mama (Yunnan College and College of Exeter) said: “A tubicolous method of life appears to have become progressively normal in the Cambrian, which may be a versatile reaction to expanding predation strains in the early Cambrian.” This study demonstrates that unusually delicate tissue protection is critical in order for us to understand these ancient creatures.”

Reference: “Exceptional soft tissue preservation reveals a cnidarian affinity for a Cambrian phosphatic tubicolous enigma” by Guangxu Zhang, Luke A. Parry, Jakob Vinther and Xiaoya Ma, 2 November 2022, Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences.

DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2022.1623