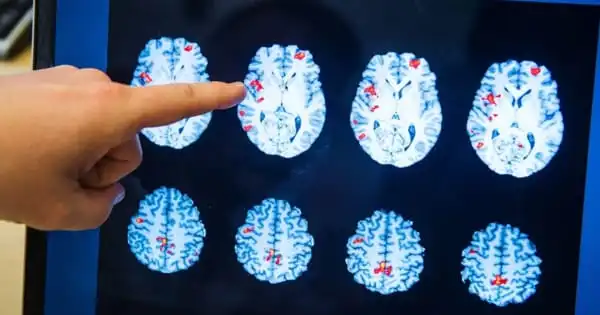

A brain region known as the hypothalamus is smaller in women who use birth control pills compared to non-users, according to a recent study. According to a new study, birth control tablets may slightly affect the structure of women’s brains.

According to a new study presented today at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America, women taking oral contraceptives, also known as birth control pills, had considerably reduced hypothalamus volume compared to women who did not take the pill (RSNA).

The hypothalamus, which is located at the base of the brain above the pituitary gland, generates hormones and helps regulate vital bodily functions such as body temperature, mood, appetite, sex drive, sleep cycles, and heart rate.

According to the researchers, structural effects of sex hormones, including oral contraceptives, on the human hypothalamus have never been observed. This could be due to the lack of approved methods for statistically analyzing hypothalamic MRI scans.

“There has been a paucity of research on the effects of oral contraceptives on this small but vital part of the living human brain,” said Michael L. Lipton, M.D., Ph.D., FACR, professor of radiology at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and medical director of MRI Services at Montefiore Medical Center in New York City. “We validated methods for measuring hypothalamic volume and confirm for the first time that current oral contraceptive pill use is associated with lower hypothalamic volume.”

We discovered a huge difference in the size of brain areas between women who used oral contraceptives and those who did not. This preliminary study demonstrates a robust relationship and should stimulate more research into the effects of oral contraceptives on brain anatomy and their possible impact on brain function.

Professor Michael L. Lipton

The study discovered that women who used the pill or oral contraceptives had a smaller hypothalamus than those who did not use the pill. The hypothalamus is a pea-sized region deep within the brain that aids in the regulation of automatic activities such as appetite, body temperature, and emotions. It also connects the neurological system to the endocrine system, which is a network of glands that generate hormones.

According to a 2019 estimate from the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, around 150 million women worldwide use oral contraceptives. Despite their ubiquitous usage, there has been little research on how oral contraceptives influence the brain. “It’s a somewhat unexplored region,” said Dr. Michael Lipton, professor of radiology at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York and the study’s lead author.

Oral contraceptives are among the most widely used methods of birth control and are also used to treat a variety of diseases such as irregular menstruation, cramps, acne, endometriosis, and polycystic ovary syndrome. According to a 2018 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics, roughly 47 million women aged 15-49 in the United States reported current usage of contraception from 2015 to 2017. 12.6 percent of those tested positive for the medication.

Indeed, the effects of oral contraceptives on the brain are not well understood. According to Nicole Petersen, a neuroendocrinology researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles, who was not involved in the study, a growing body of evidence, including the current study, suggests that there are differences in the volumes of certain brain regions in women on birth control pills. However, findings on this topic haven’t always been consistent — some studies show that women on the pill have smaller brain structures, while others show that they have larger or similar-sized structures, she says.

It’s still too early to tell how oral contraceptives affect the brain, if at all, according to Lipton. “We’re not saying folks should go out and toss away their birth control tablets,” he clarified. He went on to say that the findings could just lead to a subject that needs to be investigated further.

Dr. Lipton and colleagues recruited 50 healthy women for their study, including 21 women who were using oral contraceptives. A validated technique was utilized to assess hypothalamic volume in all 50 women who underwent brain MRI.

“We discovered a huge difference in the size of brain areas between women who used oral contraceptives and those who did not,” Dr. Lipton added. “This preliminary study demonstrates a robust relationship and should stimulate more research into the effects of oral contraceptives on brain anatomy and their possible impact on brain function.”

Other findings from the study, which Dr. Lipton classified as “preliminary,” included that a lower hypothalamus volume was related with more anger and a strong correlation with depressive symptoms. The study, however, showed no significant relationship between hypothalamic volume and cognitive function.