Vocal ways of behaving in creatures are exceptionally preserved; however, unambiguous vocalization elements can change inside and between species. There are central issues about ecological impacts, hereditary inheritability, and social learning perspectives around the advancement of these correspondences.

Postdoctoral Scientist Nicholas Jourjine at Harvard College and associates somewhat recorded and dissected the vocalizations of almost 600 mouse puppies to more likely comprehend what mice were talking about and why. The review has been distributed in the journal Current Science.

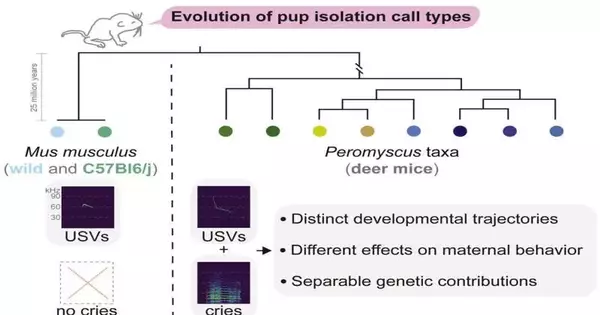

Utilizing robotized computational apparatuses to group vocalizations into particular acoustic classifications, specialists looked at the calls of deer mouse little guys across neonatal advancement in eight subspecies inside the family Peromyscus. Also, they gathered information from research center mice and wild house mice.

Though both deer mouse and lab mouse puppies created ultrasonic vocalizations, the deer mouse little guys settled on a subsequent decision type with acoustic highlights, worldly rhythms, and formative directions that were unmistakable from those of ultrasonic vocalizations. These low-recurrence apparent “cries” were generally utilized in the initial nine days of life, while ultrasonic vocalizations were fundamentally heard later.

Specialists played back the recorded little guy cries and found that deer mouse moms responded essentially quicker and moved all the more rapidly while exploring the low-recurrence apparent cries than the ultrasonic vocalizations. Specialists propose that the apparent cries are well defined for evoking earnest parental consideration right off the bat in a neonatal turn of events.

To see whether the elements of deer mouse cries and ultrasonic vocalizations were learned or rigorously hereditary characteristics, specialists pulled a trick, or cross-cultivated and explored, between two deer mouse sister species. At the point when little guy litters from the two species were brought into the world around the same time, specialists exchanged the guardians. At that point, they recorded the puppies nine days after the fact and contrasted the accounts with litters from every species that were not traded.

Cross-cultivating didn’t influence the rate, mean recurrence, or length of the puppies’ low-recurrence cries, proposing areas of strength for a premise. A comparative example arose with the ultrasonic vocalizations, aside from one little guy bunch that changed their vocalizations to be nearer to that of the temporary parent, proposing that a few acoustic elements might be delicate to a parental climate.

Utilizing half-and-half crosses between the two sister species, the investigation discovered that variety in vocalization rate, span, and pitch show various levels of hereditary predominance. Cry and ultrasonic vocalization highlights were viewed as isolated or convergent in second-age crossovers with various blends of parent species qualities, delineating that vocalization types are constrained by discrete acquired qualities.

Dissimilar to the deer mice, the little lab mice solely expressed themselves in the ultrasonic range, making the scientists keep thinking about whether training had diminished the vocal collection of research center mice (Mus musculus). Utilizing a remarkable exploratory populace of wild, free-living Mus musculus, they tried the vocal scope of their little guy’s cries.

They found the highlights looked to a great extent like the ultrasonic vocalizations of the research center Mus musculus. Beside showing that taming has not altogether changed lab mouse correspondence, it additionally affirms that the presence of cry vocalizations in deer mice is possible as the aftereffect of developmental uniqueness in wild populations since their last normal progenitor 25 to a long time ago.

More information: Nicholas Jourjine et al, Two pup vocalization types are genetically and functionally separable in deer mice, Current Biology (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2023.02.045