The nature and properties of materials are heavily reliant on aspect.Imagine how different life in a one- or two-layered world would be from the three aspects we’re usually familiar with. Given this, it is perhaps not surprising that fractals—objects with partial aspect—have stood out since their discovery.In spite of their clear oddness, fractals emerge in amazing spots, from snowflakes and lightning strikes to normal shores.

Scientists at the College of Cambridge, the Maximum Planck Foundation for the Material Science of Perplexing Frameworks in Dresden, the College of Tennessee, and the Universidad Nacional de La Plata have revealed an out and out new sort of fractal showing up in a class of magnets called turn frosts.

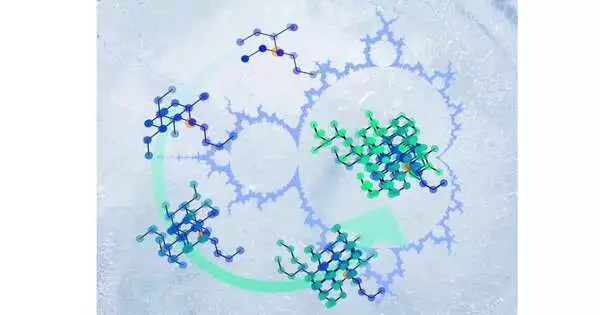

The disclosure was amazing on the grounds that the fractals were found in a perfect three-layered gem, where they routinely wouldn’t be normal. Much more amazingly, the fractals are apparent in the dynamical properties of the gem and secret in the static ones. These elements inspired the label “new dynamical fractal.”

The discoveries are distributed in the journal Science on December 15.

The fractals were found in gems of the material dysprosium titanate, where the electrons act like small bar magnets. These twists coordinate through ice and copy the limitations that protons experience in water. For dysprosium titanate, this prompts unique properties.

“When we fed this into our models, fractals appeared right away. The spin configurations were forming a network that the monopoles had to navigate. The network was branching as a fractal of the correct dimension.”

Jonathan Hallén of the University of Cambridge is a Ph.D. student and the lead author on the study.

Jonathan Hallén of the College of Cambridge is a Ph.D. student and the review’s lead author.He makes sense of the fact that “at temperatures only somewhat above outright zero, the gem turns structure into an attractive liquid.” This is no common liquid, in any case.

“With small amounts of intensity, the ice rules are broken in a few spots, and their north and south poles, making up the flipped turn, separate from one another going as free attractive monopoles,” Hallén explains.

The movement of these attractive monopolies prompted this disclosure. As Teacher Claudio Castelnovo, likewise from the College of Cambridge, brings up, “We realized there was something truly odd going on.” “Results from 30 years of tests didn’t make any sense.”

“After a few bombed endeavors to make sense of the commotion results, we at long last had an aha moment, understanding that the monopoles should be living in a fractal world and not moving openly in that frame of mind, as had always been expected,” Castelnovo said, referring to another focus on the appealing clamor from the monopoles distributed recently.

As a matter of fact, this most recent examination of the attractive clamor showed the monopole’s reality to be less than three-layered, or 2.53 layers, to be exact. Teacher Roderich Moessner, Head of the Max Planck Foundation for the Physical Science of Perplexing Frameworks in Germany, and Castelnovo suggested that the quantum burrowing of the actual twists could depend upon what the adjoining turns were doing.

As Hallén made sense of, “When we took care of this in our models, fractals quickly arose.” The setups of the twists were creating an organization that the monopoles needed to continue on. The organization was fanning itself as a fractal with a precisely perfect aspect.

Yet, why had this been missed for such a long time?

That’s what Hallén explained: “This wasn’t the sort of static fractal we regularly consider.” “All things considered, at longer times, the movement of the monopoles would really delete and revamp the fractal.”

This made the fractal undetectable by numerous regular trial methods.

Working intimately with teachers Santiago Grigera of the Universidad Nacional de La Plata and Alan Tennant of the College of Tennessee, the analysts prevailed with regards to unwinding the importance of the past trial works.

“The way that the fractals are dynamic implied that they didn’t appear in standard warm and neutron dispersing estimations,” said Grigera and Tennant. “It was simply because the clamor was estimating the monopoles’ movement that it was at last spotted.”

“Other than making sense of a few perplexing trial results that have been testing us from now on, indefinitely quite a while, the revelation of a system for the rise of another kind of fractal has prompted a completely startling course for unusual movement to occur in three aspects,” Moessner says.

Generally, the analysts are intrigued to see what different properties of these materials might be anticipated or made sense of considering the new comprehension given by their work, including connections to charming properties like geography. With turn ice being one of the most open cases of a topological magnet, Moessner said, “The limit of twist ice to show such striking peculiarities makes us confident that it holds commitment of additional amazing disclosures in the helpful elements of even basic topological many-body frameworks.”

More information: Jonathan N. Hallén, Dynamical fractal and anomalous noise in a clean magnetic crystal, Science (2022). DOI: 10.1126/science.add1644

Journal information: Science