ADHD is a neurodevelopmental condition that manifests as symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. It usually starts in childhood and can last throughout maturity. While genetics have a part in the development of ADHD, it is a complicated condition impacted by a number of genes as well as environmental factors. Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive neurological ailment characterized by cognitive decline and memory loss.

A genetic predisposition to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) can predict cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease later in life, according to a study published in the journal Molecular Psychiatry by researchers at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

Although recent big epidemiological studies have suggested a link between ADHD and Alzheimer’s disease, this is the first study to link ADHD genetic risk to the risk of acquiring late-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

“This study emphasizes what many in the field are already discussing: the impact of ADHD can be seen throughout the lifespan, and it may be linked to neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s,” said lead author Douglas Leffa, M.D., Ph.D., a psychiatry resident at UPMC.

This study emphasizes what many in the field are already discussing: the impact of ADHD can be seen throughout the lifespan, and it may be linked to neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s.

Douglas Leffa

Senior author Tharick Pascoal, M.D., Ph.D., assistant professor of psychiatry at Pitt, added that “with new treatments becoming available at earlier stages of Alzheimer’s progression, it is important to determine risk factors to help better identify patients who are likely to progress to severe disease.”

Individuals with ADHD report feeling restless and impulsive and having difficulties sustaining their concentration, which leads to a reduction in the quality of their social, educational, or professional lives, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. For a long time, ADHD was thought to be a childhood condition that people outgrew once they reached adulthood. ADHD is increasingly recognized as a childhood disorder that can persist into adulthood. ADHD symptoms in adults may be more varied and subtle than in children and adolescents, and it can be more challenging to identify in older adults.

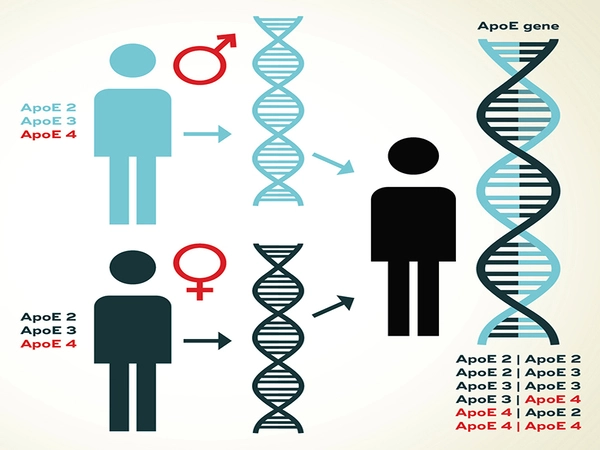

Not unlike other behavioral disorders, ADHD has a genetic component. But there is no one single gene that will dictate whether its carrier will go on to develop ADHD. Rather, that risk is determined by a combination of small genetic changes.

Researchers employed a previously created method called ADHD polygenic risk score, or ADHD-PRS, which shows the combined genetic likelihood of getting the illness when the full genome sequence is considered. Because large-scale studies that follow people with ADHD diagnosed in childhood into old life are scarce, the researchers were forced to work with an insufficient collection of data. Rather than depending on clinical diagnosis, they used genetic propensity to ADHD in their study sample.

To conduct the study, researchers used a database of 212 adults without cognitive impairments, such as predisposition to other Alzheimer’s ‘s-related mental health impairments such as dementia, at baseline. The database included brain scans, baseline amyloid and tau levels measured on PET scans and in the cerebrospinal fluid, and results of regular cognitive assessments over the course of six consecutive years. Crucially, researchers also had access to those patients’ genome sequences.

Researchers were able to show that a higher ADHD-PRS can predict subsequent cognitive deterioration and the development of Alzheimer’s brain pathophysiology in the elderly who were previously not cognitively impaired by calculating each patient’s individual ADHD-PRS and matching it with that patient’s signs of Alzheimer’s disease.

While the study findings are intriguing and suggest that the link between ADHD-PRS and Alzheimer’s should be investigated further, the researchers warn against overgeneralizing their findings and urge families to remain aware but calm. Because the database demography was limited to patients who were white and had more than 16 years of schooling on average, more study is needed to extend the findings’ relevance beyond a small segment of the American populace.

Furthermore, additional study is needed to evaluate whether ADHD therapies can alter the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in the future. Because of the nature of longitudinal studies, a final answer may take several decades, however the team is already attempting to recruit more volunteers from underrepresented backgrounds and undertake follow-up testing.