Genome sequencing is the process of sequencing an organism’s whole genome. The capacity to sequence DNA to screen for harmful modifications is critical for identifying disease genes and associated mutations. A genomic scan was conducted by researchers at Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center to explore for mutations in a gene considered a crucial building block for tiny structures that make proteins reached an unexpected turn.

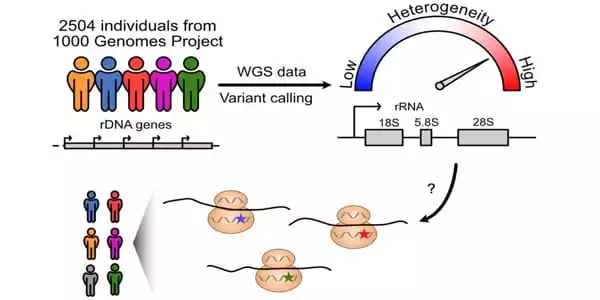

The Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center scientists discovered that ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes, which were assumed to be comparable among people, vary dramatically depending on a person’s geographic heritage. A section is known as 28S rRNA, a key component of the protein-translating ribosome, had particularly significant variability.

Human ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes are required for the formation of ribosomes, which are machineries that translate proteins. The findings of the study, which will be published in the journal RNA, indicated that these genes, which were assumed to be comparable among people, differed dramatically depending on a person’s geographic heritage. A section known as 28S rRNA, a key component of the protein-translating ribosome, had particularly significant variability.

The team, led by Marikki Laiho, M.D., Ph.D., director of molecular radiation sciences in the Department of Radiation Oncology and Molecular Radiation Sciences, diverged from their usual research focus of developing new molecules that could potentially be useful in the treatment of cancer to investigate a basic biology concept.

The analysis results exceeded our expectations. We saw excellent conservation of sequences throughout large swaths of the gene, followed by highly varied regions in exactly the locations we predicted to be unmodified. This shows that the way variable rRNAs are formed into ribosomes may cause changes in how the ribosomes function.

Marikki Laiho

They had created cancer medications that inhibited the synthesis of ribosomal rRNAs, a novel pathway that causes cancer development. Cancer cells cannot multiply in the absence of them. The researchers questioned if the rRNA gene was mutated in tumors and how this may affect their targeting method. Despite the significance of this gene, no authoritative reference sequence has been published to yet.

Team members set out to use high-performance computers at the Maryland Advanced Research Computing Center, a joint venture operated by The Johns Hopkins University and the University of Maryland, to adopt a bioinformatics approach to rRNA gene sequences. They needed to know if there were any mutations in the human population before they could start tracking cancer changes. The rRNA gene sequence was thought to be “untouchable,” or so essential that any alterations seemed unlikely.

“However, as soon as we started that study, we found that the cancer genomes were exceedingly abnormal,” Laiho explains. “In order to determine whether that aberration is real – that is, whether it changes in a specific disease – we needed to better understand what a normal human gene looks like.”

They next analyzed variations in 2,504 people from 26 populations using whole-genome sequencing data from the 1000 Genomes Project (an international human genetics database). They discovered 3,791 different locations on the rRNA gene. This comprised 470 different locations on 28S rRNA. The majority of these variations were found on large projecting folds of rRNA that differed between species. These are positions of diversity that may or may not be evolving in the future.

“The analysis results exceeded our expectations,” Laiho explains. “We saw excellent conservation of sequences throughout large swaths of the gene, followed by highly varied regions in exactly the locations we predicted to be unmodified. This shows that the way variable rRNAs are formed into ribosomes may cause changes in how the ribosomes function.”

Many of the detected variants were segregated by population. Some mutations, for example, were significantly more common in African or Asian groups than in American or European populations, and vice versa. According to Laiho, this raises the likelihood that some of the mutations are ancient, ancestry-dependent, and have been maintained in present populations.

“It’s too early to speculate on what these mutations imply, but what’s fascinating is that they’re retained by population, which implies that their survival is essential,” she says.

According to Laiho, the study findings indicate a need to functionally examine how the 28S rRNA variations alter ribosome functions, which could lead to better focused therapy for cancer or other disorders.