Following quite a while of examination and two past medication improvement endeavors, things are looking encouraging for a group of College of Arizona scientists dealing with a less poisonous therapy for a particular sort of breast disease.

The specialists have fostered a medication compound that seems to stop disease cell development in what’s known as triple-negative bosom malignant growth. The medication, which has not yet been tried in people, has been demonstrated to kill tumors in mice with practically no impact on typical sound cells, making it possibly nontoxic for patients.

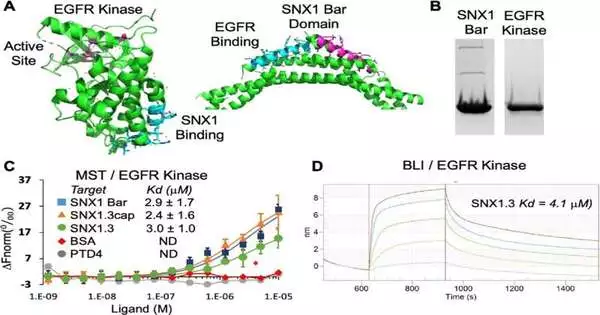

The treatment depends on a newfound way that a quality known as epidermal development factor receptor, or EGFR, prompts malignant growth. EGFR is a long-examined oncogene—a quality that in specific conditions can change a cell into a growth cell.

The specialists’ discoveries are published in the journal Malignant Growth Quality Treatment, and the group is attempting to get Food and Medication Organization endorsement to test the compound in Work 1. Clinical Preliminaries in people.

“EGFR has been recognized to be an oncogene for six decades, and there are a lot of medications out there trying to target it, but they all had limitations that didn’t make them usable as drugs for breast cancer.”

Joyce Schroeder, who co-wrote the paper with lead author Benjamin Atwell

Triple-negative bosom malignant growth represents around 10 to 15% of all bosom diseases. Triple-negative alludes to the way that the disease cells test negative for the three different kinds of bosom malignant growth — those determined by an excess of estrogen, a lot of progesterone or an over-the-top protein called HER2, as indicated by the American Malignant Growth Society. Triple-negative bosom malignant growth is more normal in women under 40 who are dark or who have a particular change in a quality called BRCA1. A portion of all instances of triple-negative bosom disease overexpress the EGFR oncogene, as indicated by the Public Establishments for Wellbeing.

The UArizona specialists contrived a compound that blocks EGFR from going to a piece of the cell that drives the endurance of the disease. The compound closes down the working of the EGFR protein that is demonstrated in malignant growth cells but not ordinary cells.

Frequently, drugs aren’t designated sufficient in their assault, so they will go after pieces of other, solid cells, bringing about undesirable secondary effects. The analysts needed to forestall that.

“EGFR has been known to be an oncogene for quite a long time, and there are a ton of medications out there attempting to target it. However, they all had restrictions that didn’t make them serviceable as medications for breast disease,” said Joyce Schroeder, who co-composed the paper with lead creator Benjamin Atwell, a postdoctoral understudy in the Division of Sub-atomic and Cell Science.

Schroeder heads the college’s Branch of Atomic and Cell Science and leads the lab where the exploration for the paper was conducted. She is likewise an individual from the college’s BIO5 Establishment and Malignant Growth Community.

The initial two medication advancements that she and her group made attempted to kill the disease cells, but they had issues.

In their most memorable endeavor, the specialists designated what Schroeder called an “unstructured” part of the EGFR protein, and accordingly, the compound couldn’t act predictably and dependably.

The subsequent endeavor brought about a compound that was too summed up and hit a piece of the protein that likewise drove typical exercise in sound cells, making the medication poisonous.

To be successful, Schroeder and her group realized that they needed to foster a compound that could enter a disease cell and focus on the specific right piece of the proteins made by the EGFR kinase to prevent malignant growth from spreading. They prevailed in their third endeavor.

“It resembled the Goldilocks impact,” Schroeder said.

She and her group realized they needed to find an answer that wouldn’t influence an ordinary cell and that would stay dynamic inside the body.

“At the point when we tried the medication in creature models, we came up with this astounding outcome where it really didn’t prevent the cancers from going, it made them relapse and disappear, and we’re seeing no poisonous secondary effects,” she said. “We are so amped up for this since it’s very growth explicit.”

Like planning a key to fit an unmistakable lock, sub-atomic and cell researchers preferably configure drug science that will cooperate with the objective protein in the specific right manner and that’s it.

“Focusing on triple-negative bosom malignant growth has been troublesome on the grounds that it doesn’t have one of these undeniable things to target,” Schroeder said. “Individuals have known for quite a while that triple-negative bosom disease cells express EGFR, but when the realized EGFR drugs were tossed at it, it didn’t answer.”

Numerous specialists felt that perhaps EGFR ought not be the objective, so they searched for new ones. Schroeder, then again, thinks EGFR is simply working such that scientists don’t yet have any idea. She and her group endeavored to target it in an original manner, with progress.

The subsequent stage, other than human preliminaries, is to test the medication’s capacity to stifle metastasis, which happens when disease cells spread to different pieces of the body, Schroeder said.

The specialists have been attempting to safeguard the protected innovation and further put resources into authorizing the resource with Tech Send off Arizona, the college office that popularizes college advancements.

More information: Benjamin Atwell et al, Sorting nexin-dependent therapeutic targeting of oncogenic epidermal growth factor receptor, Cancer Gene Therapy (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41417-022-00541-7