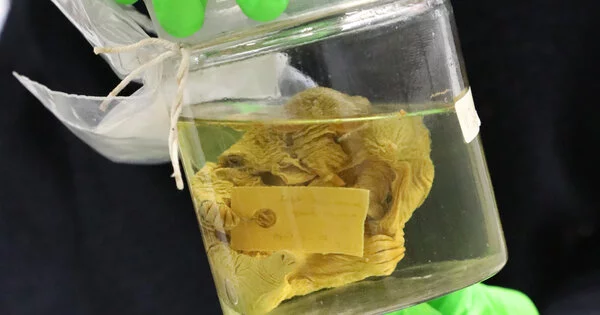

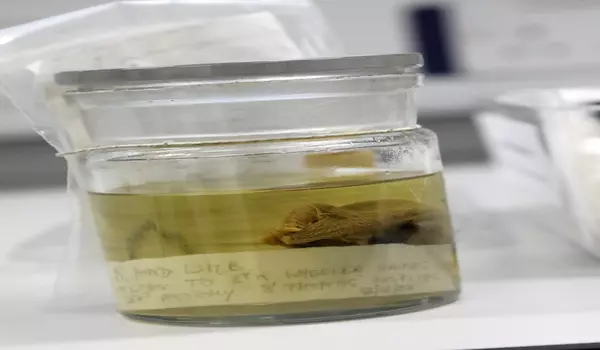

Containers of minuscule platypus and echidna examples, gathered in the last part of the 1800s by the researcher William Caldwell, have been found in the stores of Cambridge’s University Museum of Zoology.

At the time of their assortment, these examples were vital to demonstrating that a few warm-blooded animals lay eggs—a reality that steered logical reasoning and upheld the hypothesis of advancement.

“It’s one thing to read 19th-century reports that platypuses and echidnas lay eggs. But having tangible specimens here, bringing us back to that discovery nearly 150 years ago, is fairly incredible.”

Jack Ashby, Assistant Director at the museum

This remarkable assortment had not been indexed by the exhibition hall, so as of not long ago, staff had been ignorant of its presence. The intriguing find was made when Jack Ashby, Assistant Director at the exhibition hall, was doing research for another book on Australian vertebrates.

It’s one thing to peruse the nineteenth-century declarations that platypuses and echidnas really lay eggs. In any case, to have the actual examples here, tying us back to that disclosure just about a long time ago, is really astonishing, “said Ashby.

He added, “I knew as a matter of fact that there is definitely not a characteristic historical assortment on Earth that truly has a complete index of everything in it, and I thought that Caldwell’s examples truly should be here.” He was correct. Three months after Ashby asked Collections Manager Mathew Lowe to watch out, a little box of examples was found in the gallery with a note proposing they were Caldwell’s. Ashby’s examinations affirmed this was to be the situation.

Until Europeans first experienced platypuses and echidnas during the 1790s, it had been expected that all vertebrates would bring forth live young. Whether or not a few well-evolved creatures lay eggs then, at that point, became perhaps the greatest inquiry of nineteenth century zoology, and was controversial in logical circles. The newfound assortment of little containers addresses the gigantic logical undertaking that went into tackling this secret.

“In the nineteenth century, numerous moderate researchers would have rather not accepted that an egg-laying vertebrate could exist, since this would uphold the hypothesis of development — the possibility that one creature bunch was equipped to change into another,” said Ashby.

He added, “Reptiles and frogs lay eggs, so the possibility of a vertebrate laying eggs was excused by many individuals—I think they felt it was corrupting to be connected with creatures that they considered “lower living things.”

A Platypus example in the Cambridge University Museum of Zoology Cambridge University is to blame.

The newfound assortment incorporates echidnas, platypuses, and marsupials at different life stages, from prepared egg to immaturity. Caldwell was quick to make total assortments of each and every life phase of these species — albeit not each of the examples that have been found in the historical center.

For a very long time, European naturalists had been endeavoring to find verification that platypuses and echidnas lay eggs—including by asking Aboriginal Australians—but any outcomes they sent home were disregarded or excused.

William Caldwell was shipped off to Australia in 1883—with significant monetary support from the University of Cambridge, the Royal Society, and the British Government—to determine the well established secret.

In a broad hunt, Caldwell gathered around 1,400 examples with the assistance of a huge gathering of Aboriginal Australians. In 1884, the group in the end tracked down an echidna with an egg in her pocket, and a platypus with one egg in her home and another about to be laid.

This was the authoritative evidence Caldwell had been searching for, and the news was sent all over the planet. The provincial logical foundation was clearly able to acknowledge this outcome now that it had been affirmed by “one of their own.”

Ashby explains that throughout the course of recent hundreds of years, researchers have reliably put down Australian vertebrates by portraying them as odd and second-rate. He accepts that this language keeps on influencing how we portray them today and subverts endeavors to save them.

“Platypuses and echidnas are not strange, crude creatures—as numerous memorable records portray them—they are pretty much as advanced as anything else. It’s simply that they’ve laid constant eggs,” he said, adding, “I believe they’re totally astonishing and most certainly worth esteeming.”

The plume-covered echidnas are the most widespread warm-blooded animals in Australia. They cover the entire mainland and have adjusted to living in all environments—from snow-covered mountains through to the driest deserts.

Platypuses are one of the few warm-blooded creatures capable of distinguishing power and one of the few vertebrates capable of delivering toxin. When the first examples were brought to Europe, people assumed they were forgeries that had been sewn together.

Both platypuses and echidnas have an extraordinary blend of attributes that nineteenth century researchers thought ought to exist independently in either vertebrates, reptiles, or birds. This made them vital to banter and advancement.

Ashby’s new book, “Platypus Matters: The Extraordinary Story of Australian Mammals,” will be distributed in the UK on May 12, 2022 by HarperCollins.