Visual landmarks allow an animal to determine its orientation in respect to its surroundings. Dartmouth scientists discovered a novel sort of neuron in the rat brain that appears to aid in this type of visual and spatial processing. The findings have been reported in Science Advances.

Neurons known as “head direction cells” in the rat brain have long been assumed to play a crucial part in a rat’s ability to determine the direction it is facing. These neurons become active only when the rat is facing a specific direction. A head direction cell for the north is activated if the rat is facing north. Each head direction cell is distinct to the direction the rat is facing and is referred to as a “classic head direction cell” by the Dartmouth researchers. Prior studies have revealed that these cells are engaged by a variety of inputs, including landmarks, motor and vestibular information (associated to your feeling of balance).

“Over the last couple decades, head direction cells have been identified in more and more parts of the brain, so we wanted to find out if all head direction cells behave the same way, given that different parts of the brain are responsible for different functions,” says lead author Patrick LaChance, Guarini ’21, a graduate student in psychological and brain sciences and a member of Dartmouth’s Taube Lab.

Our findings show that rodent head direction cells in the postrhinal cortex function very differently than all other head direction cells studied in the last 35 years. These neurons may encode the animal’s external context in relation to its situation and aid in anchoring a rodent’s sense of orientation.

Professor Jeffrey Taube

Each traditional head direction cell can only shoot in one direction. Scientists now show that head direction cells in the postrhinal cortex of the brain can fire in two different directions depending on visual markers in the surrounding environment.

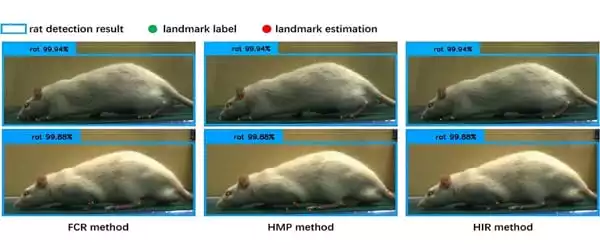

Rats were placed in a square enclosure (one rodent per trial) and had to traverse their surroundings while foraging for scattered sugar pellets as the researchers monitored head direction cell activity. The rats were subjected to a variety of visual stimuli. Initially, the enclosure had one notable visual feature, a white cardboard sheet along the south wall.

An identical white cardboard sheet was subsequently placed along the other wall (to the north) for one section of the trial, so that the visual landmark was repeated. The findings revealed that when two visual landmarks were present, the postrhinal cortex’s head direction cells became bidirectional and responded to two different directions. Classic head direction cells in other brain locations, on the other hand, were always unidirectional. When all visual markers were removed from the enclosure, the postrhinal head direction cells fired less powerfully but continued to respond to the location of the original landmark, demonstrating that they retained a memory of the landmark’s regular placement.

“We believe that postrhinal head direction cells undertake more visual estimating of head direction, whereas traditional head direction cells rely more on an internal signal that is primarily dependent on motor and vestibular input and less on a visual signal,” LaChance explains.

“Our findings show that rodent head direction cells in the postrhinal cortex function very differently than all other head direction cells studied in the last 35 years,” says senior author Jeffrey Taube, a Dartmouth professor of psychology and brain sciences. “These neurons may encode the animal’s external context in relation to its situation and aid in anchoring a rodent’s sense of orientation.”

The mouse postrhinal cortex is supposed to be similar to the human brain’s parahippocampal cortex, therefore the findings may reveal insights into humans’ sense of orientation, according to the researchers.