Xinjiang, located in northwest China, is an important crossroads between East and West Eurasia, and has historically played an important role in the exchange of products and technologies between these two regions along the Silk Road. It is a diverse blend of cultures and peoples.

The intermixing and blending of these varied communities in Xinjiang, on the other hand, may be traced back further. Bronze Age mummies recovered in the Tarim Basin were said to have western characteristics and fabrics, and the finding of literature from an extinct Indo-European language group, Tocharian, in the 5th century C.E. has piqued the interest of archeologists, linguists, and anthropologists.

A research team led by Prof. Fu Qiaomei of the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) has uncovered the previous demographic history of Xinjiang, China, using data from 201 ancient genomes from 39 archeological sites.

On March 31, their findings were reported in Science.

In the Bronze Age, there was a mix of local northern Asian and western Steppe origins.

The demographic dynamics of Bronze Age Xinjiang are critical to understanding the region’s later population dynamics. It was formerly proposed that the Tarim Basin was first settled by people related to either western Steppe Cultures (“Steppe theory”) or Central Asian groups associated with the Bactria Margiana Complex (BMAC) (“Bactrian oasis hypothesis”).

Fu and her colleagues discovered that the earliest inhabitants of Xinjiang shared genomic similarities with both of these groups, but were also broadly mixed with a unique ancestry found in local Tarim Basin mummies, who were recently shown to be linked to the Ancient North Eurasians, a population discovered 25,000 years ago in southern Siberia (ANE).

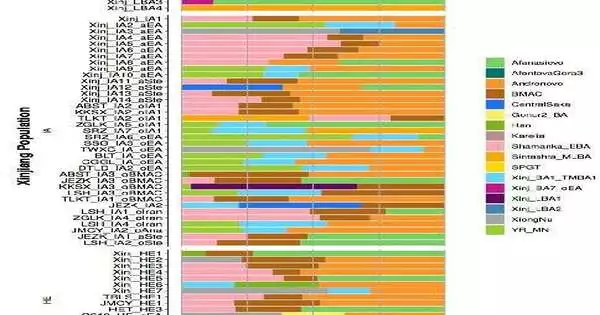

“In total, Bronze Age Xinjiang populations were discovered to contain ancestral components of the ‘local’ Tarim Basin population mixed to varying degrees with those of three groups from the surrounding regions: the Afanasievo, an Indo-European-associated Steppe culture; a group called the Chemurchek, who contained BMAC ancestry from Central Asia; and ancestry from a Northeast Asian population called the Shamanka,” said Prof. Fu, the paper’s final co-author.

The appearance of a person with almost entirely Northeast Asian ancestry in northern Xinjiang at this period suggested that these early groups were already highly migratory. This data supports a scenario in which arriving Steppe, Chemurchek, and Northeast Asian groups interacted with the region’s existing occupants, who are the closest to the oldest Tarim Basin mummies.

They discovered an influx of a newer western Steppe group associated with the Steppe Middle-Late Bronze Age (MLBA) Andronovo civilisation, as well as an increasing flood of East Asian ancestry found in southern Siberia in the latter half of the Bronze Age. Furthermore, an increase in connections with Central Asia across the Inner Asian Mountain Corridor was shown by an increase in ancestry connected to Central Asia (BMAC) during this time.

Early Indo-European speakers arrived in Bronze Age Xinjiang.

Researchers also discovered the ancestry of many Early Bronze Age individuals who were recognized as having unmixed Afanasievo heritage. This discovery supports the early arrival of these Indo-Europeans, who may have played a part in spreading the Tocharian languages to Xinjiang, the easternmost Indo-European language documented. This early date would place the advent of Indo-European languages in Xinjiang nearly contemporaneously with their arrival in Western Europe, shedding light on the origins and spread of the language family with the greatest number of speakers today.

An influx of East and Central Asians during the Iron Age established the ancestry that is still present now.

When compared to the Bronze Age, Iron Age populations saw a higher influx of individuals from East and Central Asia, with the presence of the East Asian component following a West-to-East gradient of rising East Asian ancestry. Unlike the Northeast Asian ancestry present during the Bronze Age, the East Asian ancestry present throughout the Iron Age came from a wider range of places, including mainland East Asia.

admixture proportion of the listed subgroups for BA, LBA, IA and HE populations

[Credit: Kumar et al. 2022]

These Iron Age inhabitants could be linked to Xiongnu and Han populations, which coincided with a historically known westward advance of the Xiongnu around 2200 BP following the defeat of Yuezhi in the Gansu region. Additional Iron Age migrations into Xinjiang from Central Asia or the Indus fringe region aided early activity via routes such as the Inner Asian Mountain Corridor.

The advent of ancestors associated with the Sakas, a nomadic confederation descended from Iranian peoples, in the Iron Age helps to date the arrival of Indo-Iranian languages, such as Khotanese, known to be spoken by the Sakas, in Xinjiang. This region’s Iron Age genetic profile, which linked Steppe, East Asian, and Central Asian people, was discovered to have survived into the Historical Era (HE). Despite millennia of cultural change, similar ancestries to those established in the Iron Age can still be found in modern-day Xinjiang people.

The genetic results were enriched by a phenotypic study of many remains, the first reported for ancient Xinjiang. Throughout the Bronze Age, Iron Age, and HE, the majority of people studied had dark brown to black hair and brown eyes. In the west and north of Xinjiang, a tiny proportion of the Iron Age population had blond hair, blue eyes, and lighter skin tone, which corresponds to the appearance of Andronovo Steppe ancestors. Despite their archeologically recognized “western” traits, two Early Bronze Age Tarim Basin mummies in east Xinjiang were discovered to have had dark brown to black hair and darker skin, and a more recent third mummy from the Late Bronze Age was thought to have had a more intermediate skin tone.

With the broad population changes reported in the study, it is fascinating to see the degree of genetic continuity that has been maintained in Xinjiang over the past 5000 years, said IVPP Associate Prof. Vikas Kumar, the study’s primary author.

“With the widespread population movements documented in the study, it is intriguing to see the degree of genetic continuity that has been maintained in Xinjiang over the past 5000 years.”

Associate Prof. Vikas Kumar from IVPP

What is striking about these findings is that the demographic history of a crossroads region like Xinjiang has been marked not by population replacements, but by the genetic incorporation of diverse incoming cultural groups into the existing population, transforming Xinjiang into a true “melting pot,” Prof. Fu said.

This specific component had not been so evident when simple archeological and cultural findings were considered. These findings emphasize the significance of combining genetic and archeological evidence to gain a more complete understanding of population history.

The present ancient DNA investigation emphasizes a comprehensive approach to deciphering the complex history of places like Xinjiang, where past interactions between diverse ethnicities and civilizations make thorough demographic analyses impossible. Future research in this region may disclose more about the nuances of Xinjiang’s past.