A chemical analyst and micro-extraction specialist at The University of Toledo developed a more dependable, strong, and effective way to monitor pesticide exposure and safeguard the health and safety of agricultural workers, especially in developing industries like the cannabis industry.

Dr. Analytical Chemistry Assistant Professor Emanuela Gionfriddo as well as Nipunika H. Godage, a Ph.D. candidate in the Dr. Nina McClelland Laboratory for Water Chemistry and Environmental Analysis at the University of Toledo, published a paper in the journal Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry outlining their ground-breaking technique that can identify 79 pesticide residues in human blood plasma at “ultra-trace” levels, or parts per trillion.

“This has the potential to be applied to human exposure studies for the general public, such as exposure through food or contaminated water, but, most importantly, agricultural workers who have a higher potential for acute exposure to these toxic chemicals, which typically occurs through the skin, with pesticides then passing into the bloodstream and circulating through the body,” Gionfriddo said.

“To meet the increasing demands of regulatory agencies and routine analysis laboratories, sample throughput and method tunability are critical. With automated samplers, the preparation time per sample is 1.7 minutes.”

Dr. Emanuela Gionfriddo, an assistant professor of analytical chemistry,

Pesticides are widely used in agriculture to prevent or reduce produce losses due to pests and to improve the quality of fruits and vegetables, but human exposure during mixing or application has been reported to cause neurological disorders, poisoning, cancer, reproductive disruptions, respiratory problems, and chronic kidney diseases among farm workers.

Although the U.S. S. Since these workers are less accustomed to pesticide safety equipment and procedures as well as proper pesticide storage and handling, the recent legalization of cannabis in several states, according to Gionfriddo of the Environmental Protection Agency, has resulted in “inexperienced” farmers being exposed to the dangerous chemicals.

Her study’s chosen pesticides are those that are most frequently applied when growing cannabis.

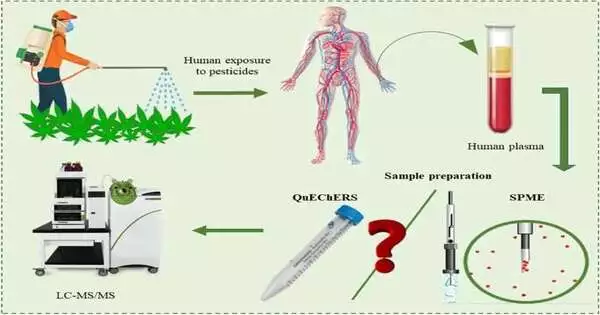

Gionfriddo’s novel testing technique combines liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry with biosolid-phase microextraction.

Sample throughput and method tunability, according to Gionfriddo, are crucial to meeting the growing demands of regulatory agencies and routine analysis laboratories. “With automated samplers, each sample takes 1:07 minutes to prepare.”.

Additionally, it is crucial for any method to quantify pesticides at low concentrations because occupational exposure to pesticides can happen at a range of concentration levels. In comparison to the widely used approach known as QuEChERS, which stands for Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe but can be labor-intensive with prolonged workflows, the new testing method demonstrated higher sensitivity, precision, and accuracy as well as a drastic reduction in abnormalities.

National Farmworker Awareness Week was last week, and the U.S. According to the EPA, exposure to pesticides occurs outside of fields. Pesticide take-home exposure, according to the federal agency, can happen when farm workers return home with pesticide residues on their bodies, clothing, hats, boots, tools, lunch coolers, or other items from their workplace. These pesticide residues could then be ingested by their children.

For the sake of the health and safety of employees and their families, as well as to address errors in pesticide application and storage and stop further exposure, Godage said it is essential to assess pesticide exposure quickly and thoroughly. “Our new technique can simultaneously extract and analyze a wide range of pesticides from human plasma.”.

More information: Nipunika H. Godage et al, Quantitative determination of pesticides in human plasma using bio-SPME-LC–MS/MS: a robust tool to assess occupational exposure to pesticides, Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry (2023). DOI: 10.1007/s00216-023-04589-8