As ice sheets overall retreat because of environmental change, chiefs of public parks need to understand what’s not too far off to plan for what’s to come. Another review from the University of Washington and the National Park Service estimates 38 years of progress for ice sheets in Kenai Fjords National Park, a dazzling gem around two hours south of Anchorage.

The review, published Aug. 5 in The Journal of Glaciology, finds that 13 of the 19 icy masses show significant retreat, four are somewhat steady, and two have progressed. It likewise finds patterns in which icy mass sorts are vanishing quickest. The almost 670,000-section of land park has different ice sheets: some end in the sea, others in lakes or ashore.

“These icy masses are a major attraction for the travel industry in the recreation area—they’re one of the primary things that individuals come to see,” said lead creator Taryn Black, a UW doctoral understudy in Earth and space sciences. “Park chiefs had some data from satellite pictures, flying photographs, and rehash photography, yet they needed a more complete understanding of changes after some time.”

“These glaciers are a significant magnet for tourists in the park—they’re one of the primary things that people come to see. Park administrators had some information from satellite photographs, aerial shots, and repeat photography, but they needed a more full knowledge of changes over time.”

Taryn Black, a UW doctoral student in Earth and space sciences

The information shows that lake-ending icy masses, which incorporate the famous Bear Glacier and Pedersen Glacier, are withdrawing quickest. Bear Glacier withdrew by 5 kilometers (3 miles) between 1984 and 2021, and Pedersen Glacier withdrew by 3.2 kilometers (2 miles) during that period.

“In Alaska, much of the icy mass retreat is being driven by environmental change,” said Black. “These icy masses are at an extremely low elevation. It’s perhaps making them get more rain in the colder times of year as opposed to snow, as well as warming temperatures, which is steady with other environmental concentrates on around here. “

Close to half of Kenai Fjords National Park is covered by icy ice. Icy masses assume a significant part in chiseling the recreation area’s scene. As per the new review, Bear Glacier, which was displayed here in September 2019, has withdrawn in excess of 5 kilometers (around 3 miles) from 1984 to 2021. The tidal pond at the icy mass’s base is developing as the ice sheet withdraws. Deborah Kurtz/U.S. Public Park Service

One amazing finding was that Holgate Glacier, which as a tidewater icy mass ends at the sea, has been making progress lately. Neighborhood boat administrators had revealed seeing recently uncovered land close to the icy mass’ edge in 2020. Yet, the new examination shows that the general icy mass has been progressing for around 5 years and seems to go through normal patterns of advance and retreat. The edges of the majority of the other tidewater ice sheets were somewhat steady over the review period.

The six land-ending icy masses all showed middle reactions, with most withdrawing, particularly in mid-year months, yet at a more slow rate than the lake-ending ice sheets. The main other icy mass that was exceptional during the review time frame was land-ending Paguna Glacier, which is shrouded in rock trash from an avalanche brought about by the 1964 Alaska quake. This trash protects the icy mass’s surface from softening.

To make the estimations, Black utilized 38 years of pictures caught by satellites in fall and spring to follow frames for every one of the 19 icy masses—a sum of around 600 layouts. She outwardly reviewed each picture to plan the placement of the icy mass’ edge. Dark involved a comparable methodology in late exploration to compute the pace of retreat of marine-ending ice sheets in west Greenland.

The new information for Alaska gives a gauge to concentrate on how environmental change — including hotter air temperatures, as well as changes in both the types and measure of precipitation — will keep on influencing these icy masses. Every one of the icy masses in the review is viewed as sea ice sheets since they are dependent upon the warm, wet sea environment.

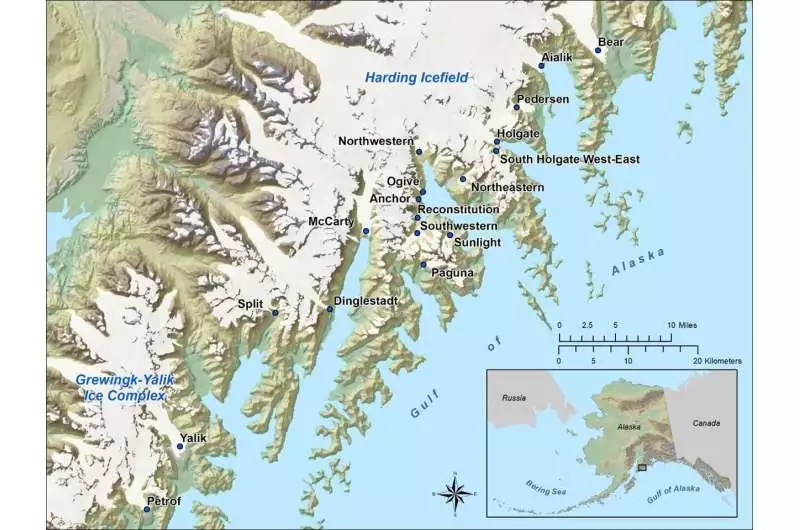

Kenai Fjords National Park is on Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula and is overwhelmed by two significant icefields. The 19 icy masses remembered for the review are displayed as blue dabs. While Alaska’s ice sheets are only a small part of the planet’s icy ice, they are losing ice quicker than some other glacierized locales beyond Antarctica and Greenland.

The review has quick application for park chiefs. These numbers aid in measuring the progressions that have occurred and will occur for the ice sheets and their immediate surroundings.

“We can’t deal with our properties well in the event that we don’t comprehend the territories and cycles happening on them,” said co-creator Deborah Kurtz at the U.S. Public Park Service in Seward, Alaska.

As the recreation area’s Physical Science Program Manager, Kurtz is likewise keen on the progressions to the encompassing stream, lake, and scene environments and how to convey those changes to general society.

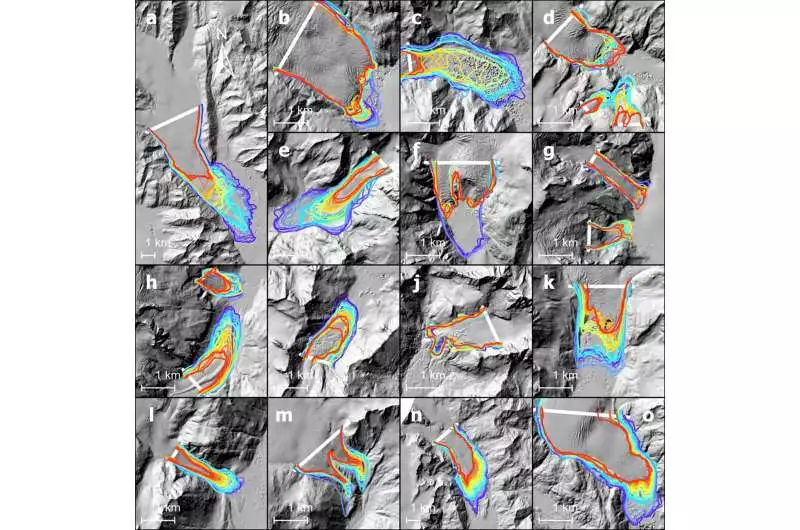

These hued frames show the edges planned for every one of the 19 icy masses that were concentrated in Kenai Fjords National Park. The variety scale goes from purple for 1984, the earliest year in the satellite pictures, to red for 2021, the latest year. A couple of the ice sheets are Bear Glacier (a), Aialik Glacier (b), and Pedersen Glacier (c), all of which have withdrawn. Holgate Glacier (d), then again, has progressed in many spots. Thirteen of the 19 ice sheets showed significant retreat.

“Translation and training are likewise significant pieces of the National Park Service mission,” Kurtz said. “This information will enable us to provide researchers and visitors with more subtleties of the progressions occurring at each specific icy mass, assisting everyone to better comprehend and value the rate of scene change we are experiencing around here.”

This study was completed as a feature of a temporary job initially planned to occur at Kenai Fjords National Park. Dark did the exploration from a distance from Seattle and visited nearby icy masses at Mount Rainier. A piece of this examination was financed by the National Park Service’s Future Park Leaders program, an organization between the Ecological Society of America and the U.S. Public Park Service.

More information: Luke Kemp et al, Climate Endgame: Exploring catastrophic climate change scenarios, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2022). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2108146119

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences