A fossil discovery from Scotland has given new data on the early development of reptiles during the age of the dinosaurs.

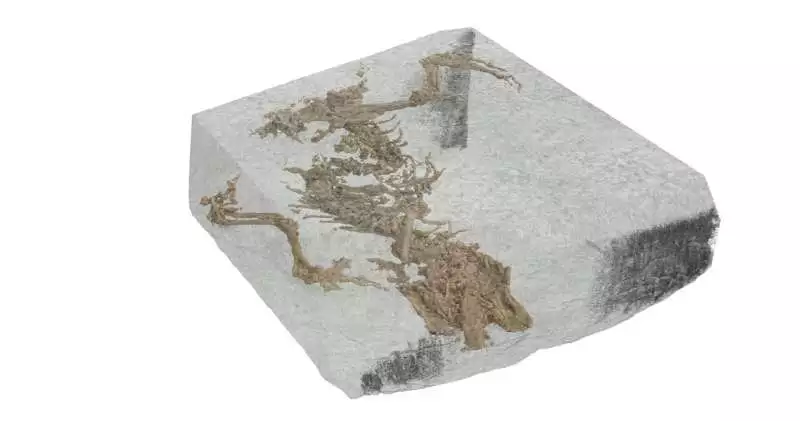

The small skeleton found on the Isle of Skye, called Bellairsia gracilis, is just 6 cm long and dates from the Middle Jurassic, quite a while back. The uncommon new fossil contains a close-to-total skeleton in a life-like explanation, missing just the nose and tail. This makes it the most complete fossil reptile of this age anywhere on the planet.

Bellairsia has a combination of tribal and current elements in its skeleton, giving proof of what the precursor of the present reptiles (which are essential for the more extensive creature group known as “squamates”) could have seemed to be.

“This tiny fossil allows us to witness evolution in action. Working with such intact, well-preserved fossils from a historical period about which we know so little is unusual in paleontology.”

Dr. Mateusz Tałanda (University of Warsaw and UCL)

The exploration, a joint task between scientists at the colleges of Warsaw, Oxford, and UCL, is accounted for in the journal Nature. First creator Dr. Mateusz Taanda (College of Warsaw and UCL) said, “This little fossil gives us a glimpse of development access activity. In fossil science, you seldom have the chance to work with such complete, very much saved fossils coming from a period about which we know nearly nothing. “

The fossil was found in 2016 by a group led by Oxford College and Public Galleries Scotland. It is one of a few new fossil disclosures from the island, including early creatures of land and water and vertebrates, which are uncovering the development of significant creature bunches that endure to the current day.

The real fossil of Bellairsia gracilis is a fossil squamate from the Center Jurassic matured rocks of the Isle of Skye, Scotland. Fossil Fossil is held in the assortments at Public Galleries Scotland. Photographer: Dr. Elsa Panciroli

Dr. Taanda remarked, “Bellairsia has some advanced reptile highlights, similar to qualities connected with cranial kinesis—that is, the development of the skull bones according to each other. This is a significant useful element of many living squamates. “

Co-creator Dr. Elsa Panciroli (Oxford College Gallery of Normal History and Public Exhibition Halls Scotland), who found the fossil, said, “It was one of the main fossils I found when I started dealing with Skye. The little dark skull was jabbing out from the pale limestone, yet it was so small that I was fortunate to detect it. Looking nearer, I saw the small teeth, and acknowledged I’d found something significant, yet we had no clue until later that practically the entire skeleton was in there. “

Squamates are the living gatherings that incorporate reptiles and snakes and include in excess of 10,000 species today, making them perhaps one of the most species-rich living vertebrate creature gatherings. They incorporate creatures as different as snakes, chameleons, and geckos, and are seen around the world. The gathering is described by various specific elements of the skull and the rest of the skeleton.

Despite the fact that we know the earliest beginnings of squamates lie a long time back in the Triassic, an absence of fossils from the Triassic and Jurassic has made their initial development and life systems hard to follow.

An advanced picture of the fossil of Bellairsia gracilis inside the stone, as uncovered utilizing microCT check information. Credit: Advanced rendering by Matthew Humpage/NorthernRogue.

Examining the new fossil close to living and extinct fossil squamates confirms Bellairsia’s place in the squamate “stem.”This implies that it split from different reptiles not long before the beginning of the current gatherings. The exploration likewise upholds the observation that geckos are an early ferning heredity and that the cryptic fossil Oculudentavis, recently proposed to be a dinosaur, is likewise a stem squamate.

To concentrate on the example, the group utilized X-beam computed tomography (CT), which, similar to clinical CT, considers painless 3D imaging. This permitted the analysts to picture the whole fossil, despite the fact that the majority of the example is as yet concealed by encompassing stone. While clinical scanners work on the millimeter scale, the Oxford College CT scanner uncovered subtleties down to many micrometers.

Portions of the skeleton were then imaged in much more significant detail, including the skull, hindlimbs, and pelvis, at the European Synchrotron (ESRF, Grenoble, France). The synchrotron bar’s power enables a goal of 4 micrometers, revealing subtleties of the skeleton’s smallest bones.

Co-creator teacher Roger Benson (Branch of Studies of the Planet, College of Oxford), said,”Fossils like this Bellairsia example have immense value in filling holes in how we might interpret development and the historical backdrop of life on the planet. It used to be extremely difficult to concentrate on such small fossils like this, yet this study shows the force of new methods, including CT checking, to picture these non-damagingly and exhaustively. “

The hands-on work site on the Isle of Skye in Scotland, where the fossil was found. including Prof. Roger Benson (College of Oxford). Credit: Dr. Elsa Panciroli.

Co-creator Teacher Susan Evans (UCL), who originally depicted and named Bellairsia from a couple of jaw and skull bones from Oxfordshire a long time back, added, “It is great to have a total example of this enticing little reptile, and to see where it fits in the developmental tree. Through fossils like Bellairsia, we are acquiring a superior understanding of early reptile life systems. Angus Bellairs, the reptile embryologist after whom Bellairsia was initially named, would have been glad. “

The review was driven by Dr. Mateusz Taanda (College of Warsaw) and involved analysts from the College of Oxford’s Studies of the Planet Division, the Oxford College Gallery of Normal History, UCL (College School London), the European Synchrotron Radiation Office, the Regular History Exhibition hall in London, and the Public Historical Centers of Scotland.

The review will be published in Nature.

More information: Mateusz Tałanda, Synchrotron tomography of a stem lizard elucidates early squamate anatomy, Nature (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-05332-6. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-022-05332-6

Journal information: Nature