A group of Columbia University specialists has revealed new proof that mental irregularities seen in neuropsychiatric problems might be detectable by modified movement in the thalamus during youthfulness, a period of elevated weakness for schizophrenia.

The study, which was published on May 19 in the journal Nature Neuroscience, holds out hope for more targeted treatment for schizophrenia and other mental illnesses where mental breakdown is linked to altered prefrontal cortex function.

“Mental deficiencies are key to schizophrenia, yet the hidden systems actually stay muddled,” said Christoph Kellendonk, Ph.D., academic administrator in psychiatry and atomic pharmacology and therapeutics and senior creator of the paper. “This study puts emphasis on the thalamus and its significance during youth in directing prefrontal cortex circuit development. We trust that our discoveries will motivate future examinations to unravel the impacts of thalamic cores on the prefrontal cortex and mental control, preparing for new treatment choices. “

“This study focuses on the thalamus and its role in regulating prefrontal cortical circuit growth during adolescence. We hope that our findings will spur more research into the effects of thalamic nuclei on the prefrontal cortex and cognitive control, paving the path for new therapeutic options.”

Christoph Kellendonk, Ph.D., associate professor in psychiatry and molecular pharmacology

Brain abnormalities seen early

Schizophrenia, a debilitating brain disorder characterized by irrational reasoning and mind flights, is typically diagnosed in young adults, with men in their late teens to mid 20s and ladies in their late 20s to mid 30s being the typical age of onset.The strange formative direction of the mind seems, by all accounts, to be laid out during improvement, well before clinical side effects of the sickness show up in early grown-up life.

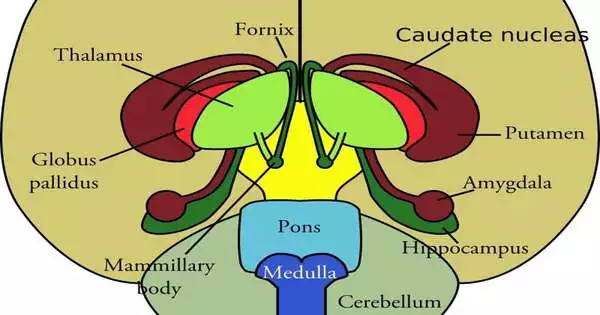

The prefrontal cortex, a region of the brain responsible for executive functions such as planning, working memory, and motivation control, has long been implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia.The thalamus is a cerebrum structure that directs prefrontal cortex activity in adults.In any case, its job during juvenile advancement is slippery.

To test how cortical improvement might veer off-track in the illness, Laura Benoit, first creator and a MD, Ph.D. graduate understudy at Columbia, controlled the action of thalamic neurons in the minds of mice during youth and analyzed what it meant for prefrontal cortex work sometime down the road.

Rescuing cognitive impairment

The researchers found that thalamic restraint during youth prompted grown-up deficiencies in attentional set-moving—a type of mental adaptability that is hindered in people with schizophrenia. Strikingly, excitation of the thalamus during adulthood turned around the mental shortfall in mice with formatively adjusted cortical capacity.

“This shows that even in a formatively changed cerebrum, supporting thalamic capacity can in any case protect mental disabilities,” said Sarah Canetta, Ph.D., Assistant Professor in Psychiatry, who co-authored the review with Dr. Kellendonk and Alexander Harris, MD, Ph.D., Assistant Professor in Psychiatry. “Our discoveries in the mouse suggest a neurodevelopmental structure in which the thalamus plays a significant part in molding the development of the prefrontal cortex.” It has translational significance, especially for schizophrenia, and proposes a treatment procedure for improving cognizance in people. “

The review, “Juvenile thalamic restraint prompts enduring disabilities in schizophrenia,” was directed in a joint effort with the Center for Theoretical Neuroscience at Columbia’s Zuckerman Mind Brain Behavior Institute. Stefano Fusi, Ph.D., teacher of neuroscience and head specialist, and Lorenzo Posani, a postdoctoral examination researcher, added to the exploration.