Nearby lymph nodes, which are part of the immune system, are typically the first place where cancer spreads in breast cancer. From here, cancer cells can travel to the brain, lung, liver, and bones.

Cancer cells suppress anti-cancer immune responses in the lymph nodes to survive and spread, or metastasize, according to new research led by researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH).

New approaches to preventing this suppression and unleashing the immune system to fight cancer may emerge from the findings, which were recently published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

The researchers looked at and compared the gene expression patterns of individual cancer cells that were residing within breast tissue or had metastasized to lymph nodes in a breast cancer mouse model. Additionally, they investigated the behavior of immune cells when these cancer cells were present. Last but not least, the team looked at published data on how human breast cancer cells express their genes during lymph node metastasis.

“Our findings have significant implications for developing effective treatments to target lymph node metastases, prevent cancer spread to other organs, and restore anti-tumor immunity in tumor-draining lymph nodes,”

Lead author Pin-Ji Lei, Ph.D., a postdoctoral research fellow in Radiation Oncology at MGH.

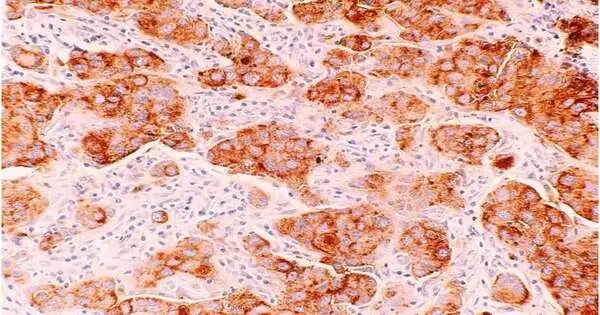

MHC class II (MHC-II) proteins, which are present on the cell surface of antigen-presenting cells and play a role in initiating immune responses, were found to be elevated in some breast cancer cells in the lymph nodes of mice and humans.

However, the so-called co-stimulatory molecules that are normally found on antigen-presenting cells and serve to warn immune cells of danger were absent from the MHC-II+ cancer cells. The lymph nodes had fewer activated immune cells and more tolerant immune cells as a result.

In mice, reducing lymph node metastasis and the expansion of tolerant immune cells by knocking out the MHC-II gene prolonged animal survival.

On the other hand, excessive expansion of tolerant immune cells and the worsening of lymph node metastasis were caused by overexpression of a protein that increases MHC-II expression.

Co-lead author Pin-Ji Lei, Ph.D., a postdoctoral research fellow in Radiation Oncology at MGH, states, “Our findings have significant implications for developing effective treatments to target lymph node metastases, prevent cancer spread to other organs, and restore anti-tumor immunity in the tumor-draining lymph nodes.”

Co-senior author Timothy P. Padera, Ph.D., associate professor of radiation oncology at Harvard Medical School and the 2021–2026 Rullo Family MGH Research Scholar, says that the group’s findings need more research to fully determine their clinical significance.

He provides the following explanation: “We need to see if cancer cell reprogramming by the lymph node microenvironment affects patients’ anti-cancer immune response.”

Ethel R. Pereira, Patrik Andersson, Zohreh Amoozgar, Meghan J. O’Melia, Hengbo Zhou, Sampurna Chatterjee, William W. Ho, Jessica M. Posada, Ashwin S. Kumar, Satoru Morita, Lutz Menzel, Charlie Chung, Ilgin Ergin, Dennis Jones, Peigen Huang, and Semir Beyaz are additional co-authors.

More information: Pin-Ji Lei et al, Cancer cell plasticity and MHC-II–mediated immune tolerance promote breast cancer metastasis to lymph nodes, Journal of Experimental Medicine (2023). DOI: 10.1084/jem.20221847