The humble chickpea has captivated palates and nourished civilizations for millennia with its nutty flavor and rich nutritional profile. This legume demonstrates culinary versatility and cultural significance, from its ancient origins to its widespread use in contemporary kitchens and restaurants worldwide. The origin, diversification, and spread of chickpeas throughout the Middle East, South Asia, Ethiopia, and the western Mediterranean have remained mysteries despite their prominence in traditional cuisine on several continents.

“Historical routes for diversification of domesticated chickpea inferred from landrace genomics,” a new study published in Molecular Biology and Evolution, sheds light on the significant effects of human migration and trade on the genetic heritage of chickpea.

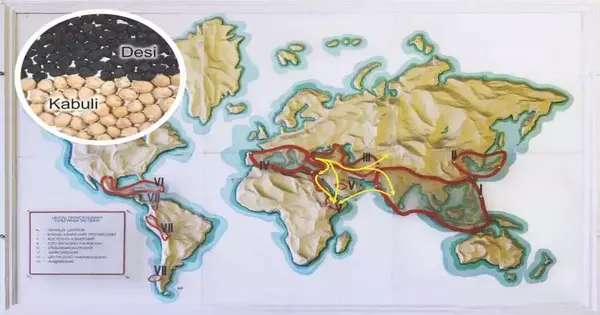

Over 400 chickpea specimens from the 1920s and 1930s were used in the study, which was led by Anna Igolkina from Peter the Great St. Petersburg Polytechnic University, Eric von Wettberg from the University of Vermont, and Sergey Nuzhdin from the University of Southern California. Despite not having a distinct geographic or genetic boundary, the collection contained both the desi and kabuli subtypes, which differ in color and size.

“Our research reveals an intriguing finding concerning the genetic relatedness of chickpea landraces from various geographic regions. In contrast to the belief that genetic similarity is dictated by linear distance, our findings imply that human transportation costs have a greater influence. This means that chickpea distribution within each region occurred mostly over trade channels, rather than through simple dispersion.”

Anna Igolkina from Peter the Great St. Petersburg Polytechnic University,

Nine distinct regions were sampled for chickpeas: Turkey, Lebanon, Ethiopia, the northern Mediterranean, the southern Mediterranean, the Black Sea, western and eastern Uzbekistan, and India. The researchers created two brand-new models for analyzing the data: popdisp, which stands for “population dispersals,” and migadmi, which stands for “migrations and admixtures.”

The popdisp model was used by the authors to comprehend how chickpeas spread throughout each region. They compared two scenarios: one in which chickpeas dispersed over long distances in a straightforward linear manner, regardless of intervening geographic barriers, and the other in which they dispersed along routes that were simpler for humans to traverse (such as potential historic trade routes).

“Our study reveals an intriguing finding regarding the genetic relatedness among chickpea landraces in different geographic regions,” states Igolkina. Our findings suggest that human movement costs have a greater impact on genetic similarity than previously thought. This is in contrast to the hypothesis that genetic similarity is determined by linear distance. This suggests that the spread of chickpeas inside every area happened prevalently along shipping lanes, as opposed to through straightforward dissemination.”

The scientists tried to find out where the Ethiopian desi population came from by using the Migadmi model. “With the tartness of the black desi chickpeas that can be found in Indian varieties, as well as a hint of sweetness,” asserts von Wettberg, “Ethiopian chickpeas have a unique flavor.”

Ethiopian chickpeas could have come from either India, as suggested by morphological similarities, or the Middle East, as suggested by evidence of human migration from western Eurasia to East Africa around 4,500 years ago. The findings, which found that Ethiopian chickpeas share ancestry with Indian, Lebanese, and Black Sea source populations, revealed that both scenarios may be true.

“The most exciting finding for me is that Ethiopian chickpeas are a mixture of Middle Eastern and South Asian ancestry,” says von Wettberg. The Semitic heritage of Ethiopians exemplifies their well-known cultural ties to the Middle East. The extent and significance of the Indian Ocean trade routes, which were an important maritime route of the Silk Road and a means by which South Asia and East Africa exchanged agricultural and cultural goods, are less well known.

The Migadmi model also showed that the Kabuli type might have come from a local population of desi chickpeas in Turkey. This refutes the linguistic claim that the Kabuli type originated in Central Asia and is named after the city of Kabul, which is now part of Afghanistan.

The implications of this study go far beyond chickpeas alone, even though these findings provide a fascinating look at the natural history of the chickpea and its connection to human migrations and trade routes.

According to Igolkina, “the importance of this work lies not only in the expansion of our knowledge of the history of chickpeas but also in the development of the two new models, popdisp and migadmi.” Analyzing migrations and admixtures in other species can be done using either of these models together or separately. Multiallelic genetic markers can be modeled using these models’ core modeling technique, compositional data analysis. This is especially important when analyzing structural variants, which are becoming more common.

von Wettberg agrees: “A focal piece of our work is growing new devices for inspecting complex movement designs. We hope that other people will use these tools to look into similar migration patterns, either in natural species or in species that are related to humans like crops, pests, and mutualists.”

More information: Anna A Igolkina et al, Historical routes for diversification of domesticated chickpea inferred from landrace genomics, Molecular Biology and Evolution (2023). DOI: 10.1093/molbev/msad110