A new report on what Ebola meant for children during an outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo suggests that children may be as helpless to the disease as adults, despite frequently showing more unobtrusive actual side effects—critical data for specialists treating pediatric patients with the dangerous illness today and in future flare-ups.

“Any pediatrician would let you know that kids are not little grown-ups. “Their bodies respond to diseases in unexpected ways,” says University of Alberta scientist Michael Hawkes, an associate professor in the field of pediatrics and senior author on the review.

“We’re solidly in the center of an Ebola episode in Uganda, and this data is of basic significance to dealing with the kids presently hospitalized with Ebola in Uganda,” he says.

“Given the modest presentations that children frequently have, or the lack of reporting of their subjective symptoms, we were curious to see if they had a similar severity in their lab data that suggest their organs are genuinely damaged by this disease,”

Lindsey Kjaldgaard, a pediatric resident at the U of A

Hawkes observes that there is almost no explicit information available on the characteristics of Ebolavirus illness in children.The analysts planned to fill in that information hole involving clinical information from the Kivu episode in Congo, which brought about almost 3,500 detailed cases from 2018 to 2020.

For the review, scientists led a review graph survey of pediatric patients alongside a correlation gathering of young adult patients. As Hawkes makes sense of, since Ebolavirus episodes normally happen in low-asset settings, there isn’t a lot of lab testing occurring. The novel wealth of lab information from the DRC episode permitted the analysts to remove key discoveries from those graphs and more thoroughly recognize how the illness presents in kids.

“Given the unobtrusive introductions kids frequently have, or the absence of revealing their emotional side effects, we were interested to check whether they had a comparable seriousness in their lab discoveries that show their organs are really impacted by this illness,” says Lindsey Kjaldgaard, a pediatric resident at the University of Arizona and first author on the review. “We wound up inferring that this is really the situation.”

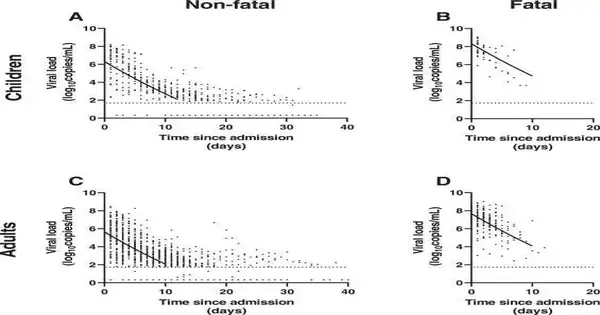

The information showed that pediatric patients had a higher viral burden at the time of confirmation and a higher peak viral burden. It likewise required greater investment for the infection to totally manifest itself in their circulatory systems, prompting longer times in clinic.

“The fact that the viral burden is higher in kids addresses an undeveloped safe framework,” says Hawkes, a Stollery Science Lab-recognized scientist and member of the Ladies and Youngsters’ Wellbeing Exploration Foundation.”Assuming that children are as helpless against Ebola as they are against other viral illnesses, it is critical to recognize that their viral burden is greater.”

The analysts likewise found that pediatric patients usually had an electrolyte-awkward nature and low glucose, two circumstances that can cause neurological and cardiac confusions and might become perilous if not treated.

“At times, children may be overlooked because they are unable to cause organ frameworks or things that are truly affected by the illness,” says Kjaldgaard.”Featuring the pediatric labs, we’re ready to look further into that and reveal a portion of those things that could somehow get missed, while grown-ups might be more ready to report those side effects.”

Concentrate on co-creator Kasereka Masumbuko. Claude, a Ph.D. student in the School of General Wellbeing, will look more closely at the various organ frameworks affected, blending and gathering a lot more background data for what’s happening in the groups of young patients.

The more data specialists have about side effects or signs to look for, the better they will actually want to address medical problems as they emerge, thus bringing down death rates among kids with Ebola, Hawkes says.

The treatment-centered viewpoint is likewise an obvious change from past ways to deal with the illness, he adds.

“Past Ebola episodes have been centered around control: detach the wiped-out patients and ensure they don’t give it to another person.” Since the western African episode, which killed 11,000 individuals, the center has been moving to, “We should really get the patients and attempt to get them better rather than simply detaching them.”

The work is distributed in the journal eClinicalMedicine.

More information: Lindsey Kjaldgaard et al, Virus kinetics and biochemical derangements among children with Ebolavirus disease, eClinicalMedicine (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101638

Journal information: EClinicalMedicine