They are the spines. The spiny pollen from plants in the sunflower family (Asteraceae), which is led by researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, both reduces infection of a common bee parasite by 81–94% and significantly boosts the production of queen bumble bees, according to two new papers.

The study, which was published in Functional Ecology and Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, provides much-needed food for thought in relation to one of the most challenging issues facing ecologists and biologists today: how to stop the massive die-off of pollinators.

Around the world, insect pollinators provide ecosystem services worth up to $200 billion annually. They are those flying, buzzing, flitting bugs that help fertilize everything from blueberries to coffee. As the lead author of the study on pollen spines, Laura Figueroa, an incoming assistant professor of environmental conservation at UMass Amherst, says, “We depend on them for diverse, healthy, nutritious diets.”. However, due to the widespread use of pesticides, habitat loss, and other factors, many pollinators are experiencing an unprecedented decline, and scientists are frantically trying to find a way to stop the apocalypse.

“It’s pointless to try to cure a common cold by starving the sufferer. To assist bees adjust to stressful conditions, we need to examine at the community level as well as what’s going on in their bellies.”

Lynn Adler, professor of biology at UMass Amherst.

One of the major advances in aiding pollinators, especially bees, is the realization that some flower species can help pollinators resist disease infections and that sunflowers are especially effective at fending off a common pathogen, Crithidia bombi, which lives in a bee’s gut.

However, until recently, no one understood why sunflowers were so successful at warding off C. bombi or if other members of the sunflower family possessed comparable anti-pathogen properties.

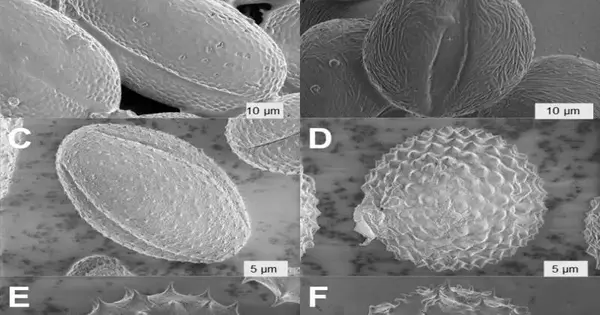

Spiny pollen from sunflower family plants (C–J), smooth pollen from buckwheat (A), red maple (B), and red maple. Credit: Functional Ecology (2023). DOI: 10.1111/1365-2435.14320

Not chemistry, but physics.

According to Figueroa, certain foods have particular chemicals that are responsible for their health benefits. “However, we are also aware that certain foods—like those high in fiber—are healthy due to their physical makeup.”.

to learn how sunflowers protect bumble bees from C. Using a spiny pollen shell as a filter to separate the chemical metabolites from the pollen’s core, Bombi, Figueroa, and their team designed an experiment. They then mixed the spiny sunflower shell, with the chemistry removed, into the pollen fed to one batch of bees, while the other batch was fed wildflower pollen dusted with sunflower metabolites but no sunflower shells.

“We found that the bees that consumed the spiny sunflower pollen shells had the same reaction as bees that consumed whole sunflower pollen and that they experienced 87 percent fewer C infections. According to Figueroa, sunflower metabolites are consumed by bugs rather than bees.

That’s not all, though. Low levels of C were found in bees fed pollen from ragweed, cocklebur, dandelion, and dog fennel—all members of the sunflower family with similarly spiny pollen shells. This raises the possibility that such disease-fighting medicinal effects may be common to plants in the sunflower family. a bombi infection similar to the bees who consumed sunflower pollen.

Food befitting a queen

The fact that sunflower pollen is low in protein and therefore not particularly nutritive in and of itself is one of the new research’s counterintuitive findings. And while the pollen might be excellent at shielding bumble bees from a gut pathogen like C. If malnutrition occurred, feeding bumble bees, sunflowers, and their relatives would be of little use.

Lynn Adler, a professor of biology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and the senior author of the study examining sunflower pollen and queen bee production, asserts that it is useless to treat the common cold if you starve the patient. In order to understand how to assist bees in responding to stressful environments, according to Adler, we need to consider both the community level and what’s going on inside the bees’ bodies.

Given that queens are how a bumble bee colony passes on its genes to the following generation, one way to measure a colony’s health is by the number of queens it produces. Moreover, queens mature rather than being born. Colonies develop a small number of bee larvae into daughter queens using the food resources they have gathered. All of the workers and the elderly queen will pass away once the cold weather arrives. The fresh daughter queens are the only bees that live. They will create a brand new colony in the spring if they make it through the winter. The likelihood that a colony’s genes will be passed down through many generations of bees increases as a colony produces more queens.

Adler and her team positioned commercial bumble bee colonies on 20 different farms in Western Massachusetts that produced varying amounts of sunflowers in order to test the effect of sunflowers on colony health. The team sampled the pathogens accumulating in the guts of their bees over a period of weeks, weighed the colonies to assess their health, and counted the number of daughter queens.

According to Rosemary Malfi, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral researcher in Adler’s lab, “we found that infection decreased with increasing sunflower abundance and, perhaps more importantly, queen bee production increased by 30% for every order of magnitude increase in the availability of sunflower pollen.”

There needs to be more investigation into the precise mechanism by which sunflower pollen helps queen bees; perhaps bumble bees have more energy for procreation if they are not battling illness, or perhaps C. bombi hinders learning and foraging, so reducing infection improves the bees’ capacity for food acquisition. According to Adler, “it’s really exciting to show that sunflower not only reduces disease but positively affects reproduction.”. “.

Figueroa and Adler make a point of emphasizing that this research does not offer a cure for the end-time insect apocalypse. One common species of non-endangered bumble bees, used in this study, was the only one used. The effects of Asteraceae pollen on other threatened bumblebee species require further study. The precise mechanism by which the spiny Asteraceae pollen defends against C is also unknown. bombi. The sunflower family may very well be involved in preserving the health of pollinators, and ultimately, the health of our own food systems, according to these preliminary results, which are encouraging.

More information: Laura L. Figueroa et al, Sunflower spines and beyond: Mechanisms and breadth of pollen that reduce gut pathogen infection in the common eastern bumble bee, Functional Ecology (2023). DOI: 10.1111/1365-2435.14320

Rosemary L. Malfi et al, Sunflower plantings reduce a common gut pathogen and increase queen production in common eastern bumblebee colonies, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (2023). DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2023.0055