CPUs are loaded with billions of tiny semiconductors that empower strong calculations, yet in addition, they create a lot of intensity. A development of intensity can slow a PC processor and make it less effective and solid. Engineers use heat sinks to keep chips cool, sometimes in conjunction with fans or fluid cooling frameworks; however, these techniques frequently require a lot of energy to operate.

Scientists at MIT have adopted an alternate strategy. They fostered a calculation and programming framework that can naturally plan a nanoscale material that can lead heat in a particular way, for example, diverting intensity in only one direction.

Since these materials are estimated in nanometers (a human hair is around 80,000 nanometers wide), they could be utilized in CPUs that can scatter heat all alone because of the material’s math.

The analysts fostered their framework by taking computational methods that have been generally used to foster huge designs and adjusting them to make nanoscale materials with characterized warm properties.

They planned a material that can lead heat along a favored course (an impact known as warm anisotropy) and a material that can effectively change heat into power. At MIT.nano, they are utilizing the last option strategy to create a nanostructured silicon gadget for waste heat recuperation.

Researchers commonly utilize a mix of mystery and experimentation to improve a nanomaterial’s capacity to conduct heat. All things considered, somebody could enter the ideal warm properties into their product framework and get a plan that can accomplish those properties, and that can sensibly be created.

As well as making CPUs that can scatter heat, the method could be utilized to foster materials that can effectively change heat into power, known as thermoelectric materials. These materials could catch squander heat from a rocket’s motors, for example, and use it to assist with driving the shuttle, which makes sense to lead creator Giuseppe Romano, an exploration researcher at MIT’s Foundation for Trooper Nanotechnology and an individual from the MIT-IBM Watson man-made intelligence Lab.

“The objective here is to plan these nanostructured materials that transport heat uniquely in contrast to any normal materials,” says senior creator Steven Johnson, a teacher of applied math and physical science who heads the Nanostructures and Calculation Gathering inside the MIT Exploration Lab for Gadgets. Yet, the inquiry is, how would you do this as effectively as could be expected, instead of simply attempting a lot of various things out of instinct? Giuseppe applied a computational plan to allow the PC to investigate numerous potential shapes and come up with the one that has the most ideal warm properties. “

Their examination papers are distributed today in Primary and Multidisciplinary Improvement.

Controlling vibrations

Heat in semiconductors goes through vibrations. Particles vibrate quicker as they heat up, making close by gatherings of atoms begin vibrating, etc., moving intensity through a material like a horde of fans doing “the wave” at a ball game. At the nuclear scale, these floods of vibrations are caught in discrete parcels of energy known as phonons.

Scientists must create nanoscale materials that control heat in unmistakable ways, such as a material that conducts more intensity in an even direction and less intensity in an upward direction.To do this, they need to control how phonons travel through the material.

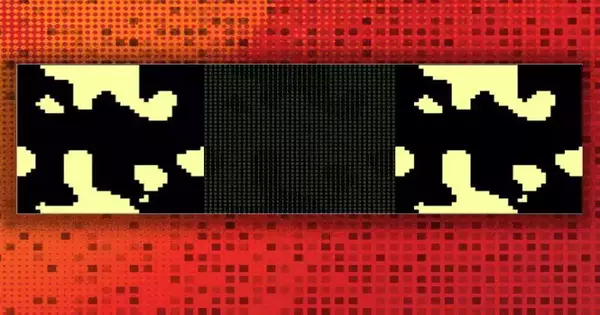

The materials they zeroed in on are known as occasional nanostructures, which are made up of a grid of designs with an erratic shape. Changing the sizes or plans of these designs can have a significant impact on the overall warmth of the framework.

On a basic level, the scientists might have made a few pieces of these designs excessively thin for phonons to go through, controlling how much intensity can go through the material. Yet, there are basically endless setups, so sorting out some way to organize them for a few explicit warm properties utilizing just instinct would have been very troublesome.

“All things considered, we acquired a computational method that was generally created for structures like scaffolds. “Imagine that we change a material into an image, and afterward we track down the best pixel conveyance that gives us the endorsed property,” says Romano.

Utilizing this computational method, a calculation needs to sort out the choice about whether to put an opening at every pixel in the picture.

“Since there are a huge number of pixels, in the event that you simply attempt every one, there are an excessive number of potential outcomes to mimic. “The manner in which you need to improve this is to begin with some estimation and afterward develop it in an approach to constantly twisting the design to make it endlessly better,” Johnson makes sense of.

Yet, this sort of enhancement is truly challenging to accomplish with nanomaterials.

For one’s purposes, the material science of warm vehicles acts diversely at the nanoscale, so the typical conditions don’t work. Also, displaying the development of phonons is particularly intricate. One should know where they are in three-layered space as well as how quickly they are moving and on what course.

Subduing complex conditions

The scientists contrived another strategy, known as the transmission addition technique, that empowers these perplexing conditions to act such that the calculation can deal with them. With this strategy, the PC can run without a hitch and constantly twist the material dispersion until it accomplishes the ideal warm properties, instead of attempting every pixel in turn.

The group also made an open-source programming framework and a web application that empowers a client to enter wanted warm properties and get a manufacturable nanoscale material design. By making the framework open source, the analysts hope to encourage different researchers to add to this area of examination.

Metal amalgams, for example, which could pave the way for new applications, are being researched.They are likewise concentrating on strategies to enhance warm conductivity in three aspects, as opposed to just evenly and in an upward direction.

Apparently, the paper by Romano and Johnson is among the initial ones in performing topological ideal material planning for nanoscale heat movement with the phonon Boltzmann transport model. “The specialized oddity of their strategy is mostly in a smart mix of a transmission addition technique with the Boltzmann transport model so the slope of the plan objective capability as for the design of the material can be determined,” says Kui Ren, a teacher of applied math at Columbia College, who was not engaged with this work.

“The thought is very novel and general, and I can envision that this thought will before long be embraced for topological planning goals with more muddled heat transport models and in numerous different systems of intensity-movement applications.”

More information: Giuseppe Romano et al, Inverse design in nanoscale heat transport via interpolating interfacial phonon transmission, Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization (2022). DOI: 10.1007/s00158-022-03392-w