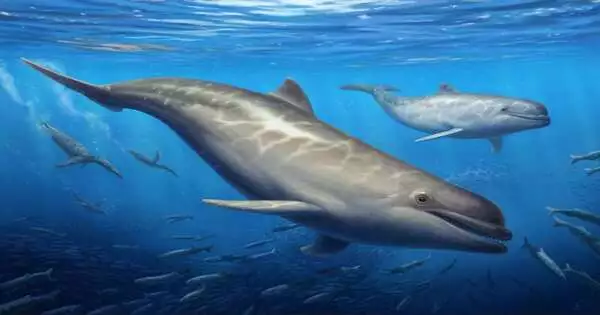

Have you ever considered the appearance of dolphins’ earliest ancestors? The new species of early odontocete known as Olympicetus thalassodon, which swam along the North Pacific coastline around 28 million years ago, is Olympicetus thalassodon.

This new species is one of a few that are assisting us with figuring out the early history and enhancement of current dolphins, porpoises, and other toothed whales. Jorge Velez-Juarbe, a Puerto Rican paleontologist who works at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, wrote a new study that was published in the open access journal PeerJ and includes a description of the brand-new species.

“Olympicetus thalassodon and its relatives possess a set of characteristics that truly distinguish them from other groups of toothed whales. According to Dr. Velez-Juarbe, Associate Curator of Marine Mammals at NHMLAC, “some of these characteristics, like the multi-cusped teeth, symmetric skulls, and forward position of the nostrils, make them look more like an intermediate between archaic whales and the dolphins we are more familiar with.”

“The teeth of Olympicetus are truly strange; they are heterodont, meaning that they show differences along the toothrow, which contrasts with the teeth of more advanced odontocetes, whose teeth are simpler and tend to look nearly the same.”

Dr. Velez-Juarbe, Associate Curator of Marine Mammals at NHMLAC.

However, Olympicetus thalassodon was not the only odontocetes found; in the same paper, the remains of two other closely related odontocetes were described. The fossils were all taken from the Pysht Formation, a geologic unit exposed along the Olympic Peninsula’s coast in Washington State. Its age ranges from 26.5 to 30.5 million years.

Olympicetus and its close relatives were also found to belong to the family Simocetidae, which is one of the earliest toothed whale diverging groups and is only known from the North Pacific. Simocetids were part of a bizarre fauna that fossils from the Pysht Formation showed included toothed baleen whales, plotopterids, an extinct group of flightless birds that looked like penguins, the bizarre desmostylians, early relatives of seals and walruses, and plotopterids.

Simicetids may have displayed distinct modes of prey acquisition and likely prey preferences, as evidenced by differences in body size, teeth, and other feeding-related structures. According to Dr. Velez-Juarbe, “this stands out against the teeth of more advanced odontocetes, whose teeth are simpler and tend to look nearly identical.” “The teeth of Olympicetus are truly weird,” she says. “They are what we refer to as heterodont, meaning that they show differences along the toothrow.”

However, other aspects of these early toothed whales’ biology, such as their ability to echolocate like their living relatives, remain unknown. The presence of echolocation-related structures, like a melon, can be linked to certain aspects of their skull. The next step would be to examine the earbones of subadult and adult individuals to see if this changed as they grew older, as an earlier study had indicated that neonates could not hear ultrasonic sounds.

More information: New heterodont odontocetes from the Oligocene Pysht Formation in Washington State, U.S.A., and a reevaluation of Simocetidae (Cetacea, Odontoceti), PeerJ (2023). DOI: 10.7717/peerj.15576