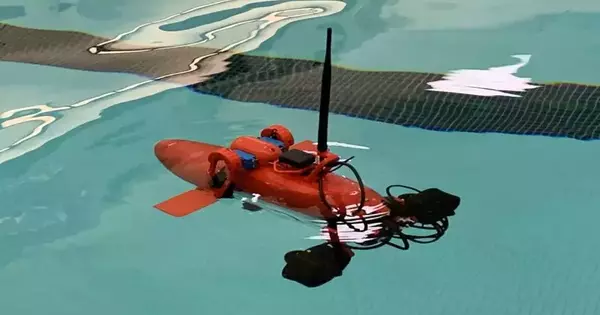

An automated semi-submersible vehicle developed at Washington State University may demonstrate that the best way to travel in water undetected and effectively is not on top or beneath, but in the middle.

The generally 1.5-foot-long semi-sub model, which worked with off-the-rack and 3D-printed parts, showed its safety in water tests, moving rapidly with low drag and a position of safety. The scientists’ definite conclusion about the test brings about a review distributed in the diary, Automated Frameworks.

This vessel type isn’t new. Specialists have found roughly made semi-subs being utilized for illegal purposes lately, yet the WSU project means to show how engineer-grown, half-lowered vessels can effectively serve military, business, and exploration purposes.

“A semi-submersible vehicle is inexpensive to produce, difficult to detect, and capable of crossing seas. Because the majority of the body is underwater, it is less vulnerable to waves than surface ships, hence there are some economic benefits as well.”

Konstantin Matveev, the WSU engineering professor leading this work.

“A semi-submersible vehicle is somewhat cheap to fabricate, hard to identify, and it can go across seas,” said Konstantin Matveev, the WSU designing teacher driving this work. “It’s not so helpless to waves in contrast with surface boats since the majority of the body is submerged, so there are a few monetary benefits too.”

Because the semi-sub cruises near the water’s edge, it doesn’t need to be made of strong materials, unlike a submarine, which must withstand the strain of being submerged for extended periods of time.The semi-sub likewise enjoys the benefit of having a little stage in touch with the air, making it simpler to get and send information.

An automated semi-submersible vehicle model was created at Washington State College.

For this review, Matveev and co-creator Pascal Spino, a new WSU graduate and previous leader of the WSU RoboSub club, guided the semi-sub in Snake Stream’s Wawawai Sound in Washington state. They tried testing its security and capacity to move. The semi-sub arrived at a maximum speed of 1.5 meters per second (generally 3.4 miles per hour), yet at higher rates, it transcends the water, making even more of a wake and using more energy. At lower speeds, it is completely drenched and barely makes a wave.

The scientists likewise equipped the semi-sub with sonar and planned the lower part of a supply line close to Pullman, Washington, to test its capacity to gather and send information.

While not yet totally independent, the WSU semi-sub can be pre-modified to act in some ways, like showing a specific course to itself or answering specific items by chasing after them or taking off.

While the WSU semi-sub is somewhat small at 450 mm long with a 100 mm width (around 1.5 feet long and 4 creeps in breadth), Matveev said it is feasible for bigger semi-subs to be worked to convey huge freight. For example, they could be utilized to assist with refueling boats or stations adrift. They could be upgraded to equal-holder ships, and because they have less drag in the water, they would use less fuel, providing both a natural and monetary benefit.

For the present, Matveev’s lab is proceeding with work on upgrading the state of semi-submersible vehicle models to fit explicit purposes. He is presently teaming up with the U.S. Maritime Foundation in Annapolis, Maryland, to chip away at the vehicles’ functional abilities and contrast mathematical recreations and results from tests.

More information: Pascal Spino et al, Development and Testing of Unmanned Semi-Submersible Vehicle, Unmanned Systems (2022). DOI: 10.1142/S2301385023500048