In excess of 5 billion individuals would pass on from hunger following a full-scale atomic conflict between the U.S. and Russia, as per a worldwide report driven by Rutgers environmental researchers that evaluates post-struggle crop creation.

“The information lets us know a certain something: We should keep an atomic conflict from truly occurring,” said Alan Robock, a Distinguished Professor of Environmental Science in the Department of Environmental Sciences at Rutgers University and co-creator of the review. Lili Xia, an associate exploration teacher in the Department of Environmental Sciences at Rutgers, is the lead creator of the review distributed in the journal Nature Food.

Expanding on past exploration, Xia, Robock, and their partners attempted to compute how much sun-impeding ash would enter the air from firestorms that would be lighted by the explosion of atomic weapons. Scientists determined ash dispersion from six conflict situations—five more modest India-Pakistan wars and a huge U.S.-Russian war—in view of the size of every country’s atomic stockpile.

This information is then placed into the Community Earth System Model, an environmental gauging device upheld by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). The NCAR Community Land Model made it conceivable to gauge the efficiency of significant yields (maize, rice, spring wheat and soybean) on a country-by-country premise. The analysts likewise analyzed extended changes to animals’ fields and in worldwide marine fisheries.

“Future work will provide even more detail to crop models. For example, heating of the stratosphere would deplete the ozone layer, resulting in higher UV light at the earth, and we need to understand the impact on food supply.”

Lili Xia, an assistant research professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences at Rutgers

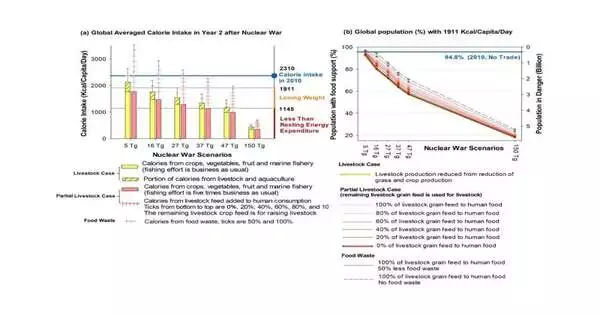

Under even the littlest atomic situation, a limited conflict between India and Pakistan, worldwide normal caloric creation diminished 7% in the span of five years of the contention. In the biggest conflict situation tried—a full-scale U.S.-Russia atomic clash—women’s normal caloric creation diminished by around 90% three to four years after the battle.

Crop declines would be the most serious in the mid-high scope countries, including significant trading nations like Russia and the U.S., which could set off export limitations and cause extreme disturbances in import-subordinate nations in Africa and the Middle East.

The scientists’ conclusion: these progressions would incite a horrendous disturbance of worldwide food showcases. Indeed, even a 7% worldwide decrease in crop yield would surpass the biggest oddity at any point recorded starting from the start of Food and Agricultural Organization observational records in 1961. Under the worst conflict situation, over 75% of the planet would be starving in two years or less.

Scientists thought about whether utilizing crops taken care of for animals as human food or lessening food waste could balance caloric misfortunes in a conflict’s quick result, yet the reserve funds were negligible under the huge infusion situations.

“Future work will add much greater granularity to the yield models,” Xia said.

“For example, the ozone layer would be obliterated by the warming of the stratosphere, creating more bright radiation at the surface, and we want to comprehend that effect on food supplies,” she said.

Environment researchers at the University of Colorado, which cooperated with Rutgers on the review, are likewise making itemized ash models for explicit urban communities, like Washington, D.C., with inventories of each and every structure to get a more exact image of how much smoke would be created.

According to Robock, scientists already have a large amount of data to realize that an atomic conflict of any size would devastate global food frameworks, killing billions of people.

“Assuming atomic weapons exist, they can be utilized, and the world has come close to atomic conflict a few times,” Robock said. “Forbidding atomic weapons is the main long-term arrangement.” The five-year-old UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons has been approved by 66 countries but none of the nine atomic states. Our work clarifies that it is the ideal opportunity for those nine states to pay attention to science and the remainder of the world and sign this deal. “

The Rutgers-driven study was led by researchers at foundations all over the planet, including Universitat Autnoma de Barcelona, Louisiana State University, the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, Columbia University, the National Center for Atmospheric Research, the University of Colorado Boulder, and Queensland University of Technology.

More information: Lili Xia, Global food insecurity and famine from reduced crop, marine fishery and livestock production due to climate disruption from nuclear war soot injection, Nature Food (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s43016-022-00573-0. www.nature.com/articles/s43016-022-00573-0

Journal information: Nature Food