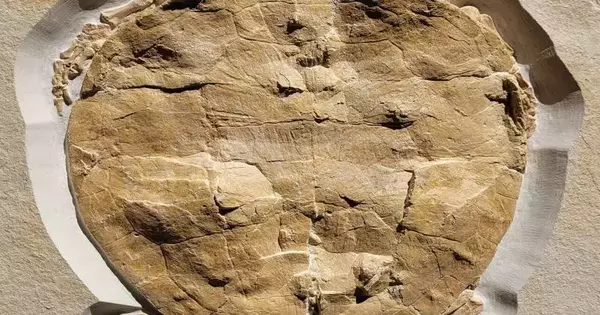

An impeccably safeguarded turtle fossil from Lower Bavaria yields significant hints about both the species and the living space that existed in southern Germany a long time ago. The fossil is the best-saved example of Solnhofia parsonsi found to date. Its forelimbs and rear appendages are relatively short, suggesting that the turtle lived close to the coast. This contrasts with the present ocean turtles, which have extended flippers and live in the vast ocean.

“No Solnhofia individual with such totally safeguarded limits has at any point been depicted,” says Felix Augustin of the Biogeology working gathering at the College of Tübingen. The head and carapace of Solnhofia parsonsi are likewise clearly saved. The nose is long and pointed, the head is three-sided, and at a little more than nine centimeters in length, it measures close to a portion of the length of the carapace.

“Solnhofia might have utilized its huge head to crush hard food things like shelled spineless creatures, as we find in a few current turtles, yet this doesn’t mean these were solely shaping its eating regimen,” says Márton Rabi of the College of Tübingen and co-creator of the review, which has now been distributed in the journal PLOS ONE.

“Solnhofia may have used its large head to crush hard food items such as shelled invertebrates, as we see in some modern turtles, but this does not imply that this was its sole diet,”

Márton Rabi of the University of Tübingen and co-author of the study,

The name Solnhofia alludes to the limestone stores of Solnhofen, a spot found south of Nuremberg in the valley of the Altmühl. Popular fossils of perhaps the earliest bird, Archaeopteryx, and of numerous pterosaurs and marine reptiles have been tracked down there.

The layers of the Solnhofen limestone, which are rich in fossils, run along the whole valley of the Altmühl. The fossil of Solnhofia parsonsi was found in a quarry in the Painten locale west of Regensburg, where deliberate searching for fossils has been happening for around 20 years.

“The generally excellent safeguarding of the fossils in the layers of limestone can be made sense of by the natural circumstances at that point,” says Andreas Matzke of the College of Tübingen and a co-creator of the review.

Quite a while ago, a shallow, tropical ocean extended across southern Germany; it contained numerous islands and reefs that isolated bowls from the vast ocean. Drifting particles sank to the bowl floors, shaping layers of limestone.

Solnhofia parsonsi, DMA-JP-2004/005, from the Upper Jurassic (Kimmeridgian) Torleite Development of Painten Detail photo of the skull in left anterolateral (A) and right sidelong view (B) Credit: PLOS ONE (2023). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0287936

If a creature passed on, its remaining parts likewise sank to the bottom. Because of the low trade of the tidal pond water with the untamed ocean, the oxygen content there was so low and the salt content so high that dead plants and creatures didn’t deteriorate. Plant and creature remains were safeguarded and fossilized in the limestone, frequently in remarkable detail.

The district is viewed as one of the world’s most significant destinations for fossils from the Mesozoic, which started quite a while ago and went on until the eradication of the dinosaurs a long time ago. The Solnhofia parsonsi fossil highlights the significance of the generally late-found site in the Painten region. The vertebrate fossils found in the limestone are currently being concentrated deductively. The Dinosaur Gallery in adjacent Denkendorf displays the finds, including Solnhofia parsonsi.

More information: Felix J. Augustin et al, A new specimen of Solnhofia parsonsi from the Upper Jurassic (Kimmeridgian) Plattenkalk deposits of Painten (Bavaria, Germany) and comments on the relationship between limb taphonomy and habitat ecology in fossil turtles, PLOS ONE (2023). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0287936