For a long time, development has been viewed as a fairly erratic interaction, with species qualities shaped by chance changes and ecological events — and thus, to a large extent capricious.

However, a global group of researchers led by specialists from Yale University and Columbia University has found that a specific plant heredity freely developed three comparative leaf types again and again in rugged locales dispersed all through the neotropics.

The discoveries gave the first models in quite a while of a peculiarity known as “reproduced radiation,” in which comparable structures develop more than once inside various locales, recommending that development isn’t generally a particularly irregular cycle, though it can be anticipated.

The review was published on July 18 in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

“The findings show how predictable evolution can be, with organismal development and natural selection combining to produce the same shapes again and over again under particular conditions. Perhaps evolutionary biology can become a much more predictive science than we ever dreamed.”

Yale’s Michael Donoghue, Sterling Professor Emeritus of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology

“The discoveries show the way that anticipated advancement can really be, with organismal turns of events and normal determination joining to create similar structures over and over under particular conditions,” said Yale’s Michael Donoghue, Sterling Professor Emeritus of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and co-relating creator. “Perhaps developmental science can turn out to be significantly more of a prescient science than we at any point envisioned previously.”

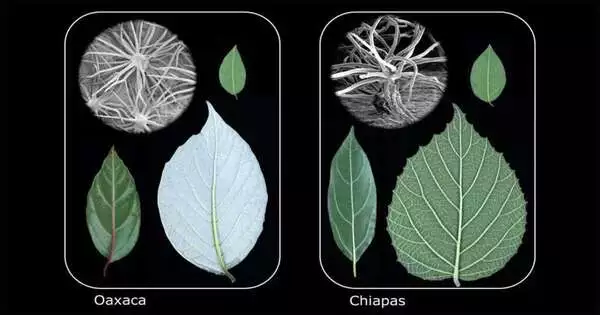

For the review, the exploration group concentrated on the hereditary qualities and morphology of the Viburnum family, a family of blooming plants that started to spread south from Mexico into Central and South America quite a while back. Donoghue concentrated on this equivalent plant bunch for his Ph.D. exposition at Harvard a long time back. At that point, he contended for an elective hypothesis where huge, hair-shrouded leaves and little smooth leaves advanced from the get-go in the development of the gathering and, afterward, the two structures moved independently, being scattered by birds, through the different mountain ranges.

The new hereditary examinations revealed in the paper, nonetheless, show that the two different leaf types developed freely, in equal measure, in every one of the various mountain locales.

“I reached some unacceptable resolution since I came up short on significant genomic information, harking back to the 1970s,” Donoghue said.

The group found that a fundamentally similar set of leaf types developed in 9 of the 11 districts contemplated. Regardless, the full range of leaf types may be unable to advance where Viburnum has only recently moved.For example, the mountains of Bolivia come up short on the enormous bushy leaf types found in other wetter regions with little daylight in the cloud timberland in Mexico, Central America, and northern South America.

“These plants showed up in Bolivia quite a while back, so we foresee that the enormous, shaggy leaf structure will ultimately develop in Bolivia too,” Donoghue said.

A few instances of duplicated radiation have been tracked down in creatures like Anolis reptiles in the Caribbean. All things considered, a similar arrangement of body structures, or “ectomorphs,” developed freely on a few distinct islands. With a plant model now close by, developmental scholars will attempt to find the overall conditions under which strong expectations can be made about transformative directions.

“This cooperative work, spread over many years, has uncovered a great new framework to concentrate on developmental variation,” said Ericka Edwards, teacher of environmental and transformative science at Yale and co-corresponding writer of the paper. “Since we have laid out the example, our next challenges are to all the more likely comprehend the useful meaning of these leaf types and the basic hereditary engineering that empowers their rehashed rise.”

Edwards and Deren Eaton of Columbia are co-creators of the paper.

More information: Michael J. Donoghue et al, Replicated radiation of a plant clade along a cloud forest archipelago, Nature Ecology & Evolution (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41559-022-01823-x