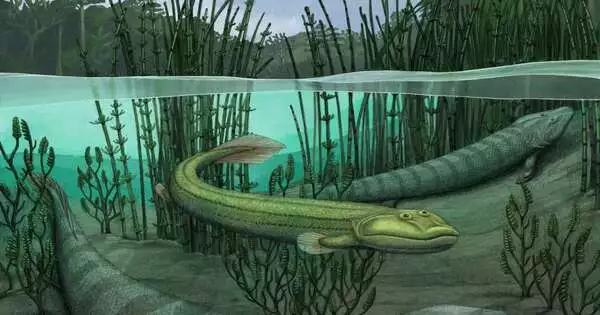

An image has been circling internet during the pandemic highlighting Tiktaalik roseae, the notable, four-legged “fishapod” that initially made the progress from water to land quite a while back. Most varieties show Tiktaalik jabbing its head out of the water and preparing to creep shorewards, while an outstretched hand undermines it with a rolled-up paper or a stick. The joke is that any of us depleted by the advanced world want to travel once again into the past, shoo it back into the water, and leave development speechless, saving ourselves from the current day of war, disease, and web images.

For reasons unknown, one of Tiktaalik’s direct relations did precisely that, choosing to get back to living in untamed water as opposed to wandering onto land. Another review from the research center of Neil Shubin, Ph.D., who co-founded Tiktaalik in 2004, depicts a fossil animal group that intently looks like Tiktaalik but has highlights that make it more suitable to life in the water than its gutsy cousin. Qikiqtania wakei was small — only 30 inches long — compared with Tiktaalik, which could grow up to nine feet. The new fossil incorporates incomplete upper and lower jaws, parts of the neck, and scales. For the most part, critically, it likewise includes a total pectoral balance with an unmistakable humerus bone that comes up short on edges that would demonstrate where muscles and joints would be on an appendage intended for strolling ashore. All things being equal, Qikiqtania’s upper arm was smooth and bended, more appropriate for a daily existence rowing submerged. The uniqueness of the arm bones of Qikiqtania recommends that it get back to rowing the water after its precursors started to involve their members in strolling.

“Because it was smaller and perhaps some of those processes hadn’t yet matured, at first we assumed it might be a juvenile Tiktaalik. However, the humerus is smooth and boomerang-shaped, and it lacks the components that would support it pushing up on land. It is incredibly distinct and makes a fresh suggestion.”

Neil Shubin, Ph.D.

“At first, we thought it was an adolescent Tiktaalik because it was smaller and perhaps some of those cycles hadn’t grown at this point,” Shubin explained.Yet, the humerus is smooth and boomerang-formed, and it doesn’t have the components that would support it pushing up ashore. It’s astoundingly unique and recommends a genuinely new thing. “

The paper, “A New Elpistostegalian from the Late Devonian of the Canadian Arctic and the Variety of Stem Tetrapods,” was published on July 20, 2022, in Nature.

An ancient pandemic venture

Shubin, who is the Robert R. Bensley Distinguished Service Professor of Organismal Biology and Anatomy at the University of Chicago, found the fossil days before Tiktaalik was found, at a site around one mile east on southern Ellesmere Island in the domain of Nunavut in northern Arctic Canada. The name Qikiatania comes from the Inuktitut word Qikiqtaaluk or Qikiqtani, the conventional name for the locale where the fossil site is found. The species assignment wakei is in memory of the late David Wake, a famous developmental scientist from the University of California at Berkeley.

Shubin and his field accomplice, Ted Daeschler, Ph.D., from the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, gathered the examples from a quarry subsequent to recognizing a couple of promising looking rocks with particular white scales on a superficial level. However, they sat away, for the most part, unexamined, while the group zeroed in on planning Tiktaalik.

After fifteen years, the disclosure of Qikiqtania turned into another pandemic story. Postdoctoral specialists Justin Lemberg, Ph.D., and Tom Stewart, Ph.D., CT-filtered one of the bigger stone examples in March 2020 and understood that it contained a pectoral blade. Tragically, it was too somewhere inside the stone to get a high-goal picture, and they couldn’t do significantly more with it once the pandemic constrained labs to close.

Lemberg, who is presently doing social asset executive hands-on work in Southern California, said, “We were attempting to gather as much CT-information about the material as possible before the lockdown, and the absolute last piece we checked was a huge, genuine block with a couple of specks of scales noticeable from the surface.” We could barely accept it when the first, grainy pictures of a pectoral balance materialized. We realized we could get a superior sweep of the block assuming we had the opportunity. That was March 13th, 2020, and the University shut down all insignificant tasks the next week. “

When grounds offices returned in the mid-year of 2020, they reached Mark Webster, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Geophysical Sciences, who approached a saw that could manage pieces off the example so a CT scanner could draw nearer and produce a superior picture. Stewart and Lemberg painstakingly denoted the limits on the block and organized a trade outside their lab in Culver Hall. The subsequent pictures uncovered an almost complete pectoral balance and upper appendage, including the unmistakable humerus bone.

“That took our breath away,” Shubin said. “This was in no way, shape, or form a captivating block from the beginning, yet we understood during the COVID lockdown when we were unable to get into the lab that the first sweep wasn’t sufficient and we expected to manage the block.” Also, when we looked at what occurred, It gave us something energizing to chip away at during the pandemic. It’s a breathtaking story. “

Brief glimpses into vertebrate history

Qikiqtania is marginally more established than Tiktaalik, yet just barely. The group’s investigation of where it sits on the tree of life places it as Tiktaalik, neighboring the earliest animals known to have finger-like digits. Be that as it may, despite the fact that Qikiqtania’s particular pectoral balance was more appropriate for swimming, it wasn’t completely fish-like by the same token. Its bended oar shape was a particular transformation, unique in relation to the jointed, built-legs or fan-formed blades we find in tetrapods and fish today.

We will quite often think creatures developed in an orderly fashion that associates their ancient structures with some living animal today, but Qikiqtania shows that a few creatures remained on an alternate path that eventually didn’t work out. Perhaps that is an illustration for those wishing Tiktaalik had remained in the water with it.

“Tiktaalik is much of the time treated as a temporary creature since seeing the stepwise example of changes from life in the water to life on land is simple. In any case, we realize that in development things aren’t generally so basic, “said Stewart, who will join the workforce at Penn State University this fall. “We don’t frequently get a look into this piece of vertebrate history. Presently, we’re beginning to uncover that variety and to get a sense of the biology and interesting variations of these creatures. It’s more than basic change with only a predetermined number of animal varieties. “

More information: Thomas Stewart, A new elpistostegalian from the Late Devonian of the Canadian Arctic, Nature (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-04990-w. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-022-04990-w