Many accept that our especially huge mind makes us human; however, is there more to it? The mind’s shape, as well as the states of its parts (curves), may likewise be significant.

The consequences of a review we distributed today in Nature, Environment, and Development show that the manner in which the various pieces of the human cerebrum developed isolates us from our primate family members. It could be said that our minds won’t ever grow up. We share this “Peter Skillet condition” with only another primate—the Neanderthals.

Our discoveries provide insight into what makes us human, but they also further limit any distinction between ourselves and our wiped-out, heavy-breasted cousins.

Following the development of the mind

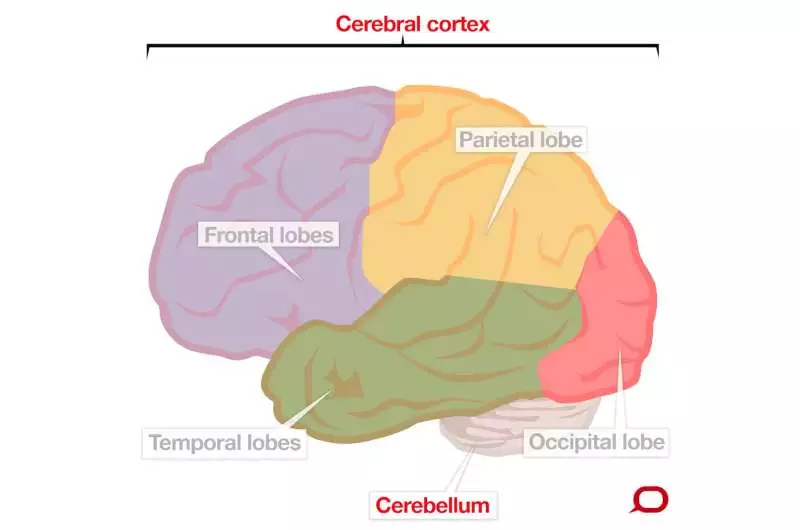

Mammalian cerebrums have four unmistakable districts or curves, each with specific capabilities. The cerebrum is related to thinking and dynamic ideas; the fleeting curve is related to safeguarding memory; the occipital curve is related to vision; and the parietal curve assists with coordinating tactile sources of information.

We investigated whether the cerebrum’s curves evolved independently of one another or whether developmental change in any one curve has all the hallmarks of being essentially attached to changes in others—that is, whether the curves’ progression is “coordinated.”

Specifically, we needed to know how human cerebrums could vary from those of different primates in this regard.

One approach to answering this question is to look at how the various curves have changed over time among different species, estimating how much shape change in each curve connects with shape change in others.

Then again, we can quantify how much the mind’s curves are incorporated with one another as a creature develops through various phases of its life cycle.

The cerebral cortex is one of the four fundamental pieces of the mind.

Does a shape change in one piece of the developing mind relate to changes in different parts? This can be instructive in light of the fact that transformative advances can frequently be backtracked through a creature’s turn of events. A typical model is the brief appearance of gill cuts in early human undeveloped organisms, which mirrors the fact that we can trace our evolution back to fish.

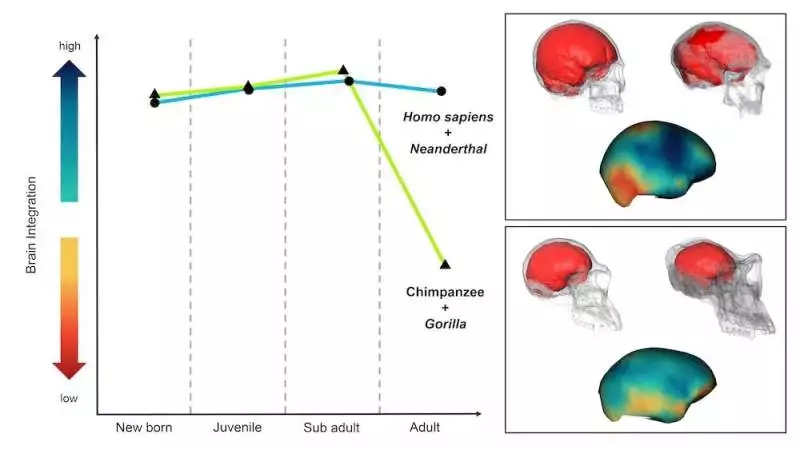

We utilized these two techniques. Our most memorable investigation included 3D mind models of many living and fossil primates (monkeys and gorillas, as well as people and our nearby fossil family members). This permitted us to plan mental advancement over the long run.

Our other advanced mind informational collection is comprised of living gorilla species and people at various developmental stages, permitting us to diagram the mix of the cerebrum’s parts in various species as they mature. Our mental models depended on CT scans of skulls. By carefully filling the cerebrum pits, you can get a decent estimation of the brain’s shape.

An astounding outcome

The aftereffects of our exams astounded us. Following change across many primate species over long periods of time, we discovered that people had especially high levels of mind incorporation, particularly between the parietal and cerebrums.

However, we additionally found that we’re not interesting. Coordination between these curves was also high in Neanderthals as well.

Seeing changes in shape through development uncovered that in primates, for example, the chimpanzee, the joining between the cerebrum’s curves is tantamount to that of people until they arrive at immaturity.

Right now, coordination quickly falls away in gorillas, yet proceeds well into adulthood in people.

Left: a graph shows the level of coordination between the mind’s curves, with cooler tones demonstrating a higher mix. Right: clear skulls of a human, Neanderthal, chimp, and gorilla, showing the carefully recreated cerebrums inside.

Neanderthals were modern individuals.

So what does this all mean? Our findings suggest that what distinguishes us from other primates isn’t simply the size of our brains.The advancement of the various pieces of our mind is all the more profoundly coordinated, and, not at all like some other living primates, we carry this directly into adult life.

A more prominent limit with regards to learning is commonly connected with adolescent life stages. We recommend this Peter Container condition because it played a strong part in the development of human knowledge.

There are other significant ramifications. Obviously Neanderthals, long described as brutish morons, were versatile, proficient, and modern individuals.

Archeological discoveries continue to provide evidence for their advancement of complex advances, ranging from the earliest known proof of string to the production of tar.Neanderthal cavern craftsmanship shows they enjoyed complex, representative ideas.

Us and them

Our outcomes further haze any lines of division between us and them. Overall, many people believe that some intrinsically superior scholarly quality gave us the upper hand, allowing us to drive our “substandard” cousins to extinction.

There are numerous reasons why one group could overwhelm or even annihilate another.Early Western researchers looked to distinguish cranial highlights connected to their own “more noteworthy knowledge” to make sense of global control by Europeans. Obviously, we currently realize skull shape doesn’t have anything to do with it.

We people may ourselves have come hazardously near elimination a long time ago.

Assuming this is the case, it’s not on the grounds that we weren’t shrewd. On the off chance that we had become wiped out, maybe the relatives of Neanderthals would today scratch their heads, attempting to sort out exactly how their “predominant” cerebrums gave them the edge.

More information: Gabriele Sansalone et al, Homo sapiens and Neanderthals share high cerebral cortex integration into adulthood, Nature Ecology & Evolution (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41559-022-01933-6

Journal information: Nature Ecology & Evolution