An exceptional investigation of mind pliancy and visual insight has tracked down that individuals who, as youngsters, had gone through a medical procedure eliminating half of their cerebrum, accurately perceived contrasts between sets of words or faces over 80% of the time. Taking into account the volume of eliminated mind tissue, the astonishing exactness features the cerebrum’s ability—and its restrictions—to overhaul itself and adjust to sensational medical procedure or awful injury.

The discoveries, distributed by College of Pittsburgh specialists today in the Proceedings of the Public Foundation of Sciences (PNAS), are the first-at any point endeavor to describe brain adaptability in quite a while and comprehend whether a solitary mind half of the globe can carry out roles normally split between the different sides of the cerebrum.

“Whether the mind is prewired with its utilitarian abilities from birth or, on the other hand, whether it powerfully builds up its capability as it develops and encounters the environment drives a lot of vision science and neurobiology,” said senior author Marlene Behrmann, Ph.D., professor of ophthalmology and brain research at the College of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University.”Working with hemispherectomy patients permitted us to concentrate on the upper limits of the utilitarian limit of a solitary cerebrum in half of the globe. With the outcomes from this review, we presently have an introduction to human brain adaptability and can at long last start looking at the capacities of mind redesign. “

“Much of vision science and neurobiology is driven by the question of whether the brain is prewired with its functional capabilities from birth or if it dynamically organizes its function as it matures and encounters its surroundings.”

Senior author Marlene Behrmann, Ph.D., professor of ophthalmology and psychology

Brain adaptability is a cycle that permits the brain to change its actions and revamp itself, either primarily or practically, because of changes in the climate. What’s more, despite the fact that mind versatility is tops right off the bat when being developed, our cerebrums keep on changing greatly into adulthood.

As people age, the two parts of our minds, called sides of the equator, become progressively more specific. Despite the fact that this division of work isn’t outright, the two halves of the globe embrace unmistakable boss liabilities: the left side of the equator develops into the essential spot for perusing printed words, and the right half of the globe develops into the essential spot for perceiving faces.

Yet, brain adaptability has constraints, and this hemispheric inclination turns out to be more unbending after some time. At times, grown-ups who sustain a cerebrum injury in view of a stroke or a growth could encounter an understanding hindrance or become face blind, contingent upon whether the left or right half of the globe of the mind is impacted.

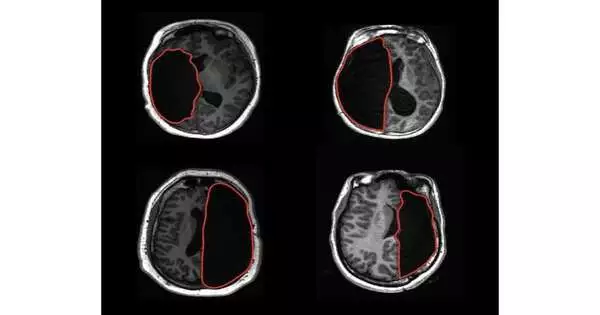

Yet, what happens when the cerebrum is compelled to change and adjust while it is still profoundly plastic? To respond to this inquiry, scientists took a gander at a unique gathering of patients who had gone through a total hemispherectomy—or a careful expulsion of one half of the globe to control epileptic seizures—during their youth.

Since hemispherectomies are generally interesting, researchers rarely approach more than a small group of patients all at once. The Pitt group tracked down a startling silver lining of the coronavirus pandemic: the standardization of telemedicine administrations, which made it conceivable to enlist 40 hemispherectomy patients, an extraordinary number for investigations of this sort.

To evaluate word acknowledgment limits, analysts introduced their member sets of words, each varying by just a single letter, for example, “cleanser” and “soup” or “tank” and “tack.” To test how well the youngsters perceived various countenances, researchers showed them sets of photographs of individuals. Either boost showed up on the screen for just a negligible portion of a second, and the members needed to conclude whether the sets of words or the sets of countenances were something very similar or unique.

Astoundingly, the single leftover side of the equator upheld both of those capabilities. The difference with regard to word and face acknowledgment between control subjects and individuals with hemispherectomies was striking, yet the distinctions were under 10%, and the typical exactness surpassed 80%. In direct examinations between matching halves of the globe in patients and controls, patients’ exactness on both face and word acknowledgment was tantamount no matter which side of the equator was eliminated.

“Reassuringly, losing half of the mind does not imply losing half of its usefulness,” said first creator Michael Granovetter, Ph.D., a student in Pitt’s Institute of Medication’s Clinical Researcher Preparation Project.While we can’t conclusively foresee how any given kid may be impacted by a hemispherectomy, the presentation that we find in these patients is empowering. The more we can grasp pliancy after medical procedure, the more data, and maybe added solace, we can give to parents who are arriving at troublesome conclusions about their youngster’s therapy plan. “

The extra creators of this paper are Sophia Robert, B.S., and Leah Ettensohn, B.S., both of Carnegie Mellon College.

More information: Michael C. Granovetter et al, With childhood hemispherectomy, one hemisphere can support—but is suboptimal for—word and face recognition, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2022). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2212936119

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences