The length of a particular age can teach us a lot about science and human social organization.With a new technique based on DNA changes, scientists at Indiana University can now determine the average age at which women and men had children throughout human history.

The specialists said this work can assist us with understanding the ecological difficulties experienced by our predecessors and may likewise help us in foreseeing the impacts of future natural change on human social orders.

“Through our research on current people, we discovered that we could predict the age at which people had children based on the types of DNA mutations they left to their children,” said focus co-creator Matthew Hahn, an IU Bloomington recognized teacher of science in the School of Expressions and Sciences and of software engineering in the Luddy School of Informatics, Processing, and Designing.”We then, at that point, applied this model to our human predecessors to figure out at what age our progenitors multiplied.”

“We discovered that the types of DNA mutations passed down to children could predict the age at which people had children. We then applied this model to our human predecessors to identify when they procreated.”

Matthew Hahn, Distinguished Professor of biology in the College of Arts and Sciences

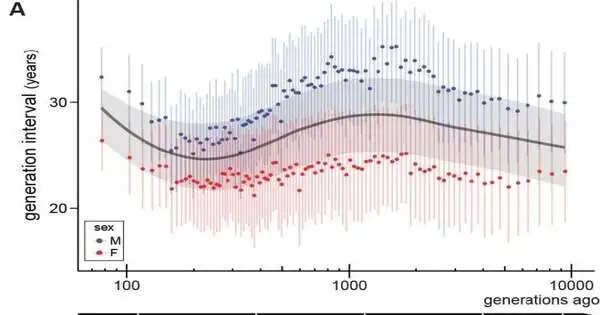

As per the review, distributed today in Science Advances and co-created by IU post-doctoral analyst Richard Wang, the typical age that people had kids over the past few years is 26.9. Moreover, fathers were reliably more established, at 30.7 years overall, than moms, at 23.2 years by and large, yet the age hole has contracted in the past 5,000 years, with the concentrate’s latest assessments of maternal age averaging 26.4 years. The shrinking gap appears to be caused in large part by mothers having children at older ages.

Aside from the new increase in maternal age at labor, the scientists discovered that parental age has not increased consistently in the past and may have dropped quite a while ago in light of population development concurrent with civilization’s ascent.

“These transformations from the past accumulate with each age and exist in people today,” Wang said. “We can now distinguish these transformations, perceive how they contrast among male and female guardians, and how they change as an element of parental age.”

Children’s DNA acquired from their folks contains approximately 25 to 75 new transformations, which permits researchers to analyze the guardians and posterity and then group the sort of change that happened. While studying changes in a large number of children, IU researchers discovered a pattern: the types of changes that children experience depend on the ages of their mothers and fathers.

Previous hereditary approaches to determining verifiable age times relied on the intensifying effects of one or more types of recombination or change in modern human DNA groupings’ dissimilarity to historical examples.Regardless, the results were found to be in the middle of the two sexes and across the age range of 40,000 to 45,000 years.

Hahn, Wang, and their colleagues developed a model that uses once-again transformations—a hereditary change that is available without precedent for one relative because of a variation or transformation in a microorganism cell of one of the guardians or that emerges in the prepared egg during early embryogenesis—to independently gauge male and female age times at a variety of focuses over the previous few years.

The researchers were not initially attempting to determine the long-term relationship between orientation and age of origin; rather, they were leading a more extensive investigation into the number of transformations passed from guardians to children.They just saw the age-based change designs while looking to comprehend contrasts and similitudes between these patterns in people versus different warm-blooded animals, like felines, bears, and macaques.

“The tale of mankind’s set of experiences is sorted out from a different arrangement of sources: written accounts, archeological discoveries, fossils, and so on,” Wang said. “Our genomes, the DNA tracked down in all of our cells, offer a sort of composition of human transformative history.” The findings of our hereditary investigation confirm some things we already knew from other sources (for example, the new rise in parental age), but they also provide a more expansive understanding of the demography of the elderly.”These discoveries add to a superior comprehension of our common history.”

Extra supporters of this exploration were Samer I. Al-Saffar, an alumni understudy at IU at the time of the review, and Jeffrey Rogers of the Baylor School of Medicine.

More information: Richard Wang, Human generation times across the past 250,000 years, Science Advances (2023). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abm7047. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abm7047

Journal information: Science Advances