Several patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have airway-clogging mucus plugs, an accumulation of mucus in the lungs that can affect quality of life and lung function. A retrospective analysis of patient data from the COPDGene study suggests that targeting mucus plugs could help prevent deaths from this fourth-leading cause of death in the United States. Mucus plugs were also linked to higher mortality, according to a new study conducted by researchers from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, a founding member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system. The findings, which were presented simultaneously at the American Thoracic Society 2023 International Conference and published in JAMA, may assist medical professionals in lowering the number of COPD deaths, one of the most prevalent and fatal respiratory conditions.

“Our findings suggest that using therapies to break up these mucus plugs could help improve outcomes for COPD patients, which is the next best thing,” said corresponding author Alejandro A. Diaz, MD, MPH, an associate scientist in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. “As a chronic disease, COPD cannot be cured.” Bodily fluid is something that we definitely know a ton about from an essential science viewpoint, and there are likewise a ton of studies focusing on bodily fluid that either as of now exist or are being developed for different illnesses, so it’s an incredibly encouraging objective.”

“The best thing that can be done for COPD sufferers is to use therapies to break up these mucus plugs because it is a chronic disease that cannot be cured.”

Alejandro A. Diaz, MD MPH, an associate scientist in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine at the Brigham.

The fourth leading cause of death in the United States is COPD, which affects 15.9 million people. Cigarette smoking or prolonged exposure to air pollutants are the most common causes. Eliminating these pollutants from one’s environment can slow the progression of COPD, but it cannot be cured. Additionally, the most common treatment strategy for COPD has largely remained unchanged for many years.

According to Diaz, “we’ve had only two targets for COPD therapies: either promoting bronchial dilation, which means making the airways themselves wider, or reducing bronchial inflammation.” ” For the last four decades, we’ve had only two targets for COPD therapies.” This indicates that there may be more we can do to combat this disease than previously thought.”

The ongoing review was an observational review examination of information from the Hereditary Study of Disease Transmission of COPD (COPDGene) study, an enormously broad clinical review that planned to explore the fundamental hereditary risk elements of COPD. Between 2007 and 2011, over 10,000 people with various stages of COPD, ranging from the mildest to the most severe, participated in the study.

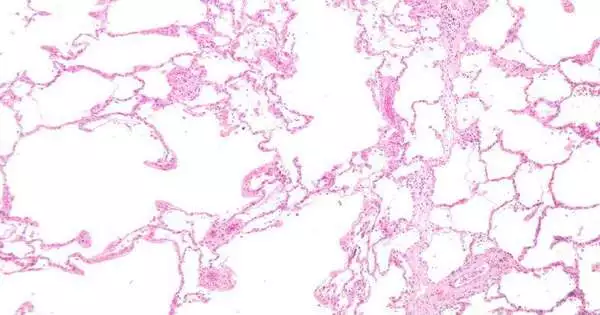

The researchers looked at data from over 4,000 of these patients for this new observational study. To figure out which patients had bodily fluid fittings, the analysts examined chest CT checks from the patients, taken at their most memorable visit to the center. The researchers were able to locate mucus plugs even in patients who did not report feeling ill because they performed CT scans on all patients regardless of their self-reported symptoms.

Diaz stated, “Mucus production is a normal part of the body’s immune response; typically, we cough it up as we get better.” COPD makes the body produce a lot of bodily fluid and makes it harder to get out, so you end up with these bodily fluid fittings that aren’t firmly related to a particular side effect and can go undetected.”

Over the course of the study, the researchers discovered that COPD patients without detectable mucus plugs had a mortality rate of 34%. For patients with bodily fluid plugs in up to two lung fragments, the death rate leaped to 46.7 percent. For patients with at least three lung fragments, the death rate was 54.1 percent.

Diaz adds, “The data show a compelling association between the accumulation of these mucus plugs and overall mortality, but we don’t know anything about what’s driving it yet.” This is because the data are based on mortality rates.

The researchers plan to test existing mucus-targeting therapies on people with COPD next to see if treating the mucus plugs could improve patient outcomes because mucus is a known therapeutic target for other diseases.

In the meantime, the research shows that there are still a few unknown factors that contribute to COPD mortality and that not all of these factors will necessarily manifest as symptoms for the patient.

“The way that these bodily fluid fittings were related to mortality across various infection stages lets us know that there are parts of COPD movement that can be gotten by a CT check regardless of whether they’re not felt by the patient,” said Diaz. “It’s not easy to say that every person with COPD needs to get a CT scan tomorrow, but clinicians should think about it when working with their patients.”