The commitment for American farming is tempting: better soil, more carbon kept in the ground, less manure overflow, and less requirement for synthetics. The truth of establishing cover crops during the slow time of year ca much-promoted and financed way to deal with environmental change relief sis more muddled, as per new Stanford College-driven research.

The review, distributed in Worldwide Change Science, uncovers that cover cropping as it is currently completed in a significant U.S. crop-developing area lessens corn and soybean yields and could prompt aberrant natural effects from extended development to compensate for the misfortunes.

“Utilization of cover crops is quickly spreading.” “We needed to understand what these new practices mean for crop yields in practice, beyond limited scope research plots,” said Jillian Deines, the review’s lead author and a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford’s Center on Food Security and the Climate (FSE), at the time of the examination.

“Agriculture is a really difficult business to get correctly, and things rarely go as planned. In our opinion, continuous monitoring, evaluation, and learning are critical components of making agriculture genuinely sustainable.”

David Lobell, the Gloria and Richard Kushel Director of FSE and professor in Earth System Science.

“Farming is a precarious business to get right, and circumstances normally don’t pan out as expected,” added senior creator David Lobell, the Gloria and Richard Kushel Head of FSE and teacher in Earth Framework Science. “Our view is that steady checking, assessment, and learning are vital pieces of making farming really feasible.”

Keeping up with vegetation cover on rural fields in the slow time of year can prompt huge decreases in overflow and spillage of nitrogen into streams and groundwater, diminished soil disintegration, and a decreased need for weed control synthetics. The training can also be an expensive system for removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Because of cover editing’s true capacity as an environmental change arrangement and other scene benefits, the United States Department of Agriculture has funded the training with more than $100 million every year since 2016.

The Expansion Decrease Act, passed in August, reserves $20 billion to “straightforwardly further develop soil carbon, lessen nitrogen misfortunes, or diminish, catch, keep away from, or sequester carbon dioxide, methane, or nitrous oxide outflows, related to rural creation.” Without these incentives, ranchers are likely to be more hesitant to incur the expense of planting and uncovering cover crops.For what it’s worth, cover crops are used on only about 5% of fields in the critical corn-growing region of the United States.

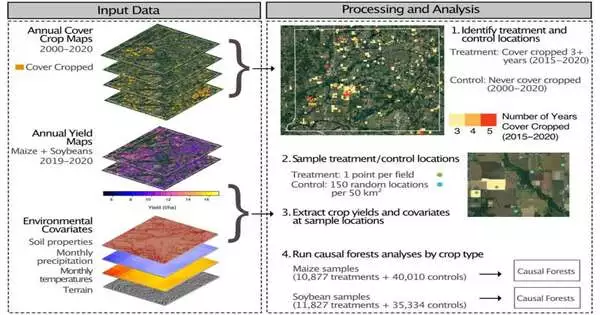

Checking out fields from space

The researchers used satellite symbolism to investigate around 20 million sections of farmland in Iowa, Indiana, Missouri, Ohio, Illinois, and Michigan in the first large-scale field-level examination of yield influences from cover editing across the US Corn Belt.They examined each field that had developed cover crops for no less than three years, contrasting them with comparable fields that had not been planted with cover crops.

Overall, fields with cover crops saw yield declines of 5.5% for corn and 3.5% for soybeans. The greater the maize yield misfortunes, the greater the harvest’s requirement for nitrogen manure, a compound that normal cover crops likewise use, and water, which cover crops can drain ahead of dry developing seasons.

The yield declines, with a deficiency of about $40 per section of land for corn and $20 per section of land for soybeans. This blunder, combined with the cost of implementing cover crops—roughly $40 per section of land—makes long haul reception of the work on testing difficult, the analysts write.

In spite of the sobering discoveries, the analysts stress that cover yields may yet demonstrate usefulness to ranchers and the remainder of society. It may be the case that the advantages require a long time to kick in, and almost certainly, ranchers will turn out to be better at execution. More exploration can assist with directing that execution by showing, among other things, how options in contrast to rye—the most commonly utilized cover crop in the U.S. Corn Belt—could bring about higher essential harvest yields in certain areas.

Guaranteeing that the cover crop is taken out with sufficient lead time prior to establishing essential harvests could lessen the probability of huge yield penalties. Policymakers could support the reception of cover editing more firmly in regions that are most drastically averse to encountering huge yield punishments, for example, those with less weakness to water pressure.

“Advancing by doing is truly significant, and changes are quite often required both in rancher practice and government strategy,” Lobell said. “The mix of satellite information and strong AI strategies can assist us in being more deft in making these changes.”

More information: Jillian M. Deines et al, Recent cover crop adoption is associated with small maize and soybean yield losses in the United States, Global Change Biology (2022). DOI: 10.1111/gcb.16489

Journal information: Global Change Biology