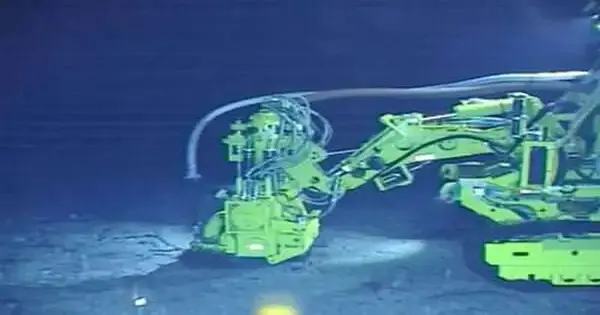

In 2020, Japan played out the principal effective test by removing cobalt hulls from the highest point of remote ocean mountains to mine cobalt, a mineral utilized in electric vehicle batteries. In addition to the fact that straightforwardly mined regions become less tenable for sea creatures, mining likewise makes a tuft of dregs that can spread through the encompassing water. An examination of the natural effect of this first test, distributed July 14 in the journal Flow Science, reports a decline in sea creatures both in and around the mining zone.

The Global Seabed Authority (ISA), which has authority over ocean bottom assets outside a given nation’s purview, still can’t seem to conclude a bunch of remote ocean mining guidelines. However, as of July 9, the ISA must either adopt a set of exploitation regulations or consider mining exploitation under existing international laws for companies seeking to mine the ocean floor for minerals like cobalt, copper, and manganese.

These pieces of information are truly vital to get out,” says first creator Travis Washburn, a benthic biologist who works intimately with the Geographical Review of Japan. “A number of these decisions are being made now because a set of regulations is expected to be finalized soon.”

“I assumed there would be no changes because the mining test was so small. They drove the machine for two hours, and the sediment plume only traveled a few hundred meters. However, it was enough to change things.”

Author Travis Washburn, a benthic ecologist.

The group dissected information from three of Japan’s visits to the Takuyo-Daigo seamount: one month before the mining test, one month later, and one year later. Subsequent to requiring a seven-day boat trip from port, a remotely operated vehicle went to the ocean bottom and gathered video of the influenced regions. One year after the mining test, scientists noticed a 43% drop in fish and shrimp thickness in the areas directly affected by residue contamination. However, they also observed a 56 percent decrease in the density of fish and shrimp in the surrounding areas. While there are a few potential explanations for this diminution in fish populations, the group figures it could be because of the mining test defiling fish food sources.

The review didn’t notice a significant change in less portable sea creatures, similar to coral and wipes. Nonetheless, the specialists note that this was solely after a two-hour test, and coral or wipes might in any case be influenced by long-haul mining tasks.

“I had accepted we wouldn’t see any progressions on the grounds that the mining test was so little. They drove the machine for two hours, and the silt crest just traveled two or three hundred meters,” says Washburn. “However, it was sufficient to alter the situation.”

The researchers say that in order to get a better understanding of how deep-sea mining affects the ocean floor, they will need to repeat this study several times. Preferably, numerous long periods of information ought to be gathered before a mining test happens to represent any regular variety in sea creature networks.

“We will require more information notwithstanding, but this study features one region that needs more clarity of mind,” says Washburn. “We’ll need to see this issue on a more extensive scale, in light of the fact that these outcomes propose the effect of remote ocean mining could be considerably greater than we naturally suspect.”

More information: Travis W. Washburn, Seamount mining test provides evidence of ecological impacts beyond deposition, Current Biology (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2023.06.032. www.cell.com/current-biology/f … 0960-9822(23)00815-1