Warm-blooded animal development in Africa, including that of current human precursors, through the late Cenozoic (Plio-Pleistocene, ~5.3 quite a while back), might not have been driven by the extension of prairies as recently suspected, a new examination has proposed.

Changes in vegetation would probably have affected the spatial scope of warm-blooded creature bunches as they adjusted to the climate, while outrageous cases might have prompted eradications and the start of new species. The degree to which vegetation is expected to change to get such huge reactions is the focal point of examination by Kathryn Sokolowski, an alumni specialist at the College of Utah, and partners.

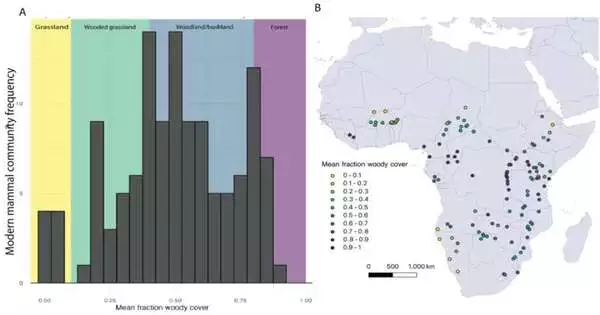

The examination group displayed 58 present-day herbivorous species and surveyed their reactions to changes in woody cover from trees and bushes across 123 parks and nature reserves all through Africa. This depended on the presence or absence of species (counting cheetahs, impala, hartebeest, squirrels, wildebeest, otters, porcupines, mongooses, jackals, zebras, monkeys, wildcats, bushbabies, giraffes, and hippos) and utilized satellites to gauge vegetation cover.

In particular, the concentrate likewise reflected well-evolved creature dietary inclinations from nibblers (eating generally grasses and herbaceous plants), programs (eating leaves and twigs of trees, bushes, and spices, in addition to a few wild natural products), frugivores (eating organic products, nuts, and seeds, in addition to establishing roots and shoots), and blended feeders (eating a mix of the previously mentioned).

The outcomes, distributed in Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, and Palaeoecology, uncover an inclination for conditions with roughly half woody (tree and bush) cover, estimated as 0.5 mean division woody cover (fwc), addressing the area of trees and bushes in comparison with grasses, herbaceous vegetation, and unvegetated regions. Not many species favored open (<0.3 fwc, with meadows being <0.1 fwc) and shut (>0.7 fwc, with woods being >0.8 fwc) scenes.

The estimations don’t consider the exact level of vegetation and homogenize specific sorts, for instance, joining forest with bushland and field with deserts over sizes of 100–1,000 km2. In any case, Sokolowski and partners can recognize that the extension of fields through the late Cenozoic might not have been a huge component influencing warm-blooded creature speciation and termination in Africa.

Just four types of gemsbok, springbok, red-fronted gazelle, and mountain zebra communicated a particular inclination for open propensity in the models, with the likelihood of decline as woody cover increments almost certain. On the other hand, 11 species showed a likelihood of decline with a shift to open meadows from closed forests, including duikers and some pronghorn.

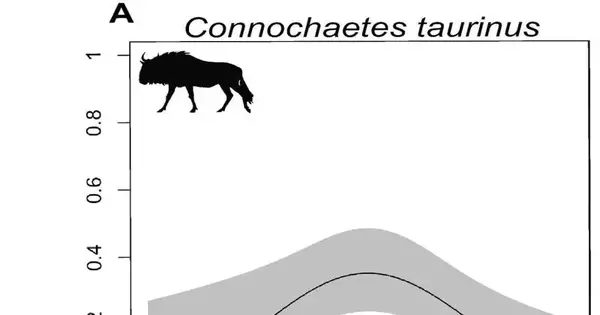

In the interim, 21 species demonstrated inside the center ground of prairie and forest cover (0.4–0.6 fwc), including impala, bison, and wildebeest, and 22 displayed no aversion to changing vegetation cover, like warthogs and hedge elephants. Dietary inclination likewise assumed a part for frugivorous animal categories, which top inside areas of high forest cover; however, programs, nibblers, and blended feeders appeared to favor blended meadow and forest conditions.

Instances of the four principal reactions communicated in the mean part of woody cover: a) unimodal blue wildebeest with an inclination for blended prairie and forest; b) obtuseness of the bushpig to evolving vegetation; c) shut forest inclination of sitatunga eland; and d) open field inclination of springbok. Credit: Sokolowski et al., 2023.

Taking into account slow eaters, programs, and blended feeders that prevail in the unimodal scope of both field and forest, the examination group reasoned that savannah environments are the most probable biological system to have multiplied in the late Cenozoic, with grass covering a huge extent of the scene, mixed by bushes and trees.

Such conditions were logically exceptionally powerless to yearly precipitation, which could move the vegetation either towards additional bone-dry circumstances that would diminish development efficiency to help enormous herbivores requiring huge amounts of food, or an excess of downpour could weaken the plant supplements to help more modest vertebrates requiring less but better food. This consequently makes sense of the shortfall of nibblers in open prairie (<0.2 fwc) and programs in forested forests (>0.8 fwc).

Connecting the cutting-edge networks to paleontological examinations, Sokolowski and collaborators propose that the remaining fossil parts are simply prone to recording a preview of the local area found at the middle value of over an enormous region and can’t be completely relied upon to recreate past scene changes. For instance, past work on fossils has proposed that bushpigs are demonstrative of thick forest, yet the consequences of this new exploration, which found the middle value of over a lot bigger regions, show that they are coldhearted toward forest cover.

Subsequently, the exploration urges alertness while involving specific fossils as “marker species” during paleoecological reproductions of mosaic natural surroundings.

More information: Kathryn G. Sokolowski et al, Do grazers equal grasslands? Strengthening paleoenvironmental inferences through analysis of present-day African mammals, Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2023.111786