The five-day Hajj, the annual Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia, that Muslims are expected to make if they are able, is anticipated to begin on June 26. Approximately 2 million pilgrims will participate in 2023, which is comparable to the annual number of pilgrims in years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Like previous generations, their visits will be enhanced and even made possible by contemporary technology.

The Saudi government has recently developed smartphone apps for pilgrim group organizations. Apps with prayer guides are used by pilgrims themselves to locate and pray at particular holy sites. Additionally, they use social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok to record their journeys, both physical and spiritual.

The country is introducing smart cards so that pilgrims can pay without cash and access Hajj services and information.

Also in 2022, the Saudi government set up an online system where people from Western Europe, Australia, and the United States could enter a digital lottery to get Hajj visas. One visa is granted for every 1,000 Muslims in countries with a Muslim majority. Travel arrangements for those granted visas must be made through the Saudi government rather than through domestic travel agencies.

News coverage of the Hajj has frequently mentioned the technology involved, describing it as a new phenomenon that is “transforming” the pilgrimage as those changes have occurred.

However, as an authority on contemporary Islam and Middle Eastern history, I am aware that technology has been at the center of the Hajj since the middle of the 18th century. Technologies for transportation and communication have long been essential to the spiritual experiences of pilgrims as well as the management of the pilgrimage by governments.

Travel innovation

As far back as the 1850s, steamship innovation made it workable for the vast majority of Muslims to make the journey regardless of whether they lived significant distances from Mecca.

“European shipping lines sought Hajj pilgrims as passengers to supplement” their profits from shipping commercial cargo through the Suez Canal, according to scholar Eric Schewe. Around the time of the Hajj, merchants were able to earn a little extra money by dropping off pilgrims at Arabian ports along a route that their ships were already taking.

Additionally, the pilgrims valued the speed, dependability, safety, and lower cost of steamship travel. As a result, they were able to get to the Hajj faster and for less money than ever before. The annual number of Hajj pilgrims quadrupled between 1880 and 1930.

Rail was advantageous for land-based travelers, particularly those from Russia, whose multi-leg journeys frequently included train travel to Odessa, which is now part of Ukraine, or another Black Sea port, where they traveled by steamship to Istanbul and then by caravan to Mecca. Steamships were advantageous for water-based travelers, while rail was advantageous for land-based travelers.

Technology for communication The telegraph also played a significant role in the Hajj. In order to rule and demonstrate its independence from European powers, the Ottoman government made use of its extensive telegraph network. From Istanbul, the country’s capital, through Damascus, Syria, to Mecca, this was a crucial link. European consular authorities, rail and steamship organizations, and, surprisingly, individual travelers were involved in the message framework for Hajj-related interchanges.

The pilgrimage was also impacted by additional communication technologies. Muslim-majority gatherings were a source of concern for colonial powers concerned about political unrest. They were also concerned about the public’s health.

Pilgrims could bring infectious diseases home due to the speed of rail and steam travel, as was the case during the cholera epidemics that occurred frequently during the Hajj in the 1800s.

Print technologies were used in the introduction of numerous tracking regulations by governments: The Dutch in 1825 started expecting pioneers to get visas, while the French in 1892 started requiring Algerian explorers to have travel licenses. In 1886, the British government awarded Thomas Cook the sole contract for Hajj travel from India, requiring pilgrims to pre-purchase tickets for each leg.

Together, these rules made it easier for pilgrims to safely complete the Hajj. However, they also worked to minimize its potential risks to public health and politics for the colonial powers that ruled the majority of Muslims worldwide.

In the modern era, the spread of commercial air travel in the 1940s further altered the Hajj’s dynamics. Compared to traveling by steamship, flying was even faster, cheaper, and safer. It offered to let more Muslims participate in the Hajj, but the number of pilgrims increased six or seven times between 1950 and 1980, posing huge logistical, political, and financial challenges.

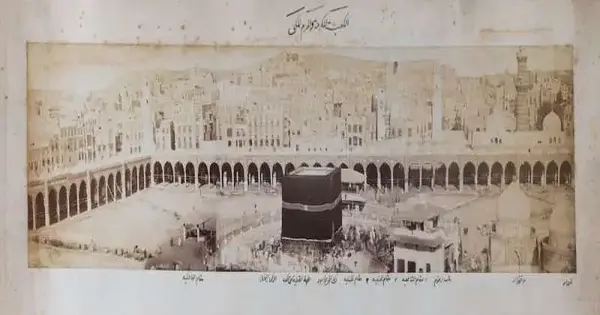

The Hajj became even more well-known thanks to new communication methods. For instance, beginning in the 1940s, Mandate Palestine’s radio stations broadcast pilgrim letters to listeners at home, covering the Hajj. Television from the 1960s showed footage of pilgrims circumambulating or walking around the Kaaba, one of the most important Hajj rituals, just like newsreels from earlier movies. They became motivated to participate in the Hajj as a result of this footage.

In the meantime, Muslims were able to read the increasing number of printed Hajj guides that helped them find places to stay, eat, and worship. The classic Middle Eastern travel literature known in Arabic as the rihla or seyahetname includes contemporary Hajj travelogues that document pilgrims’ experiences. Both terms refer to travel books that frequently include pilgrimages.

Errors occurred as pilgrims rejoiced in their ability to fly to the Hajj. In 1952, the Saudi government cut a Hajj entry tax at the last minute, allowing thousands more pilgrims to fly to Beirut, where Lebanese airlines had no seats. Instead, the US Air Force orchestrated an airlift that brought nearly 4,000 stranded pilgrims from Beirut to Mecca in time to complete the Hajj.

Again, pilgrim management relied heavily on communication technologies. In the 1950s, British-ruled Malaysia issued so-called “pilgrim passports,” which contained all of a pilgrim’s travel-related information, including vaccination dates and contact information for next of kin. In the late 2000s, Saudi Hajj visas went from being handwritten and hand-stamped in the 1970s to being digitally stamped and bar-coded.

Numerous travelers Historically, only a small number of Muslims had the idea of making the pilgrimage at some point in their lives. Even today, the majority of Muslims will never be able to perform the Hajj, and the majority of those who do will only perform it once.

However, considering that the global Muslim population is just over 2 billion, even a small portion represents a significant number. Only 0.1% of Muslims worldwide are expected to make the Hajj this year, with only 2 million participating.

Mecca’s ability to accommodate all of its visitors simultaneously has become the main obstacle as travel and communication have become easier. The Saudi Ministry of Hajj and Umrah has a lot at stake. It is anticipated that it will provide all pilgrims with a spiritually meaningful, safe, and healthy experience while avoiding negative publicity for the host nation. For Muslims, Umrah—also known as the “lesser pilgrimage”—is recommended but not required. It can be completed at any time of year and includes many of the Hajj rituals.

With its own digital tools and devices in the hands of many pilgrims, the Hajj of the 21st century fits into the nearly 200-year-old story of technology and the Hajj. While the specific technologies themselves have evolved, their significance to the management of the Hajj and the spiritual experiences of pilgrims has not.

Provided by The Conversation