A new study by an international team of researchers proposes a ‘Farming Hypothesis’ for the spread of Transeurasian languages by triangulating data from linguistics, archaeology, and genetics, tracing the origins of Japonic, Koreanic, Tungusic, Mongolic, and Turkic to the movements of Neolithic millet farmers from the West Liao River region.

The origin and early spread of Transeurasian languages, including Japanese, Korean, Tungusic, Mongolic, and Turkic, is one of the most contentious issues in Asian prehistory. Although many of the similarities between these languages are due to borrowing, recent studies have revealed a reliable core of evidence supporting Transeurasian’s classification as a genealogical group, or a group of languages that emerged from a common ancestor. Accepting the ancestral relatedness of these languages and cultures, on the other hand, raises questions about when and where the first speakers lived, how descendant cultures sustained themselves and interacted with one another, and the routes of their dispersal over millennia.

An international team of researchers from Asia, Europe, New Zealand, Russia, and the United States published a new paper in the journal Nature that provides interdisciplinary support for the farming “Farming Hypothesis” of language dispersal, tracing the Transeurasian languages back to the first farmers moving across Northeast Asia beginning in the Early Neolithic. They triangulate the time-depth, location, and dispersal routes of ancestral Transeurasian speech communities using newly sequenced genomes, an extensive archaeological database, and a new dataset of vocabulary concepts for 98 languages.

Taken alone, a single discipline cannot conclusively resolve the big questions surrounding language dispersal, but taken together, the three disciplines increase the credibility and validity of this scenario.

Martine Robbeets

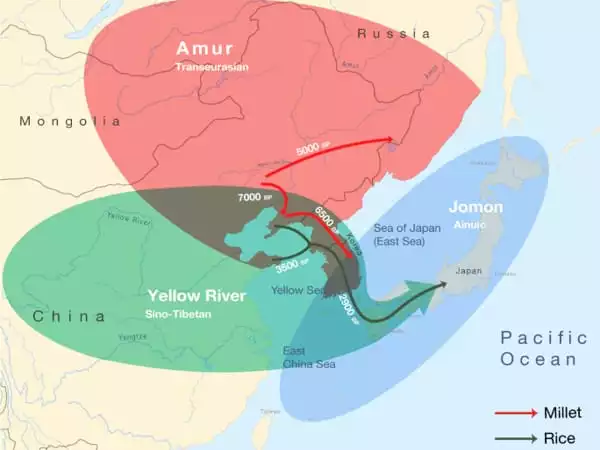

The evidence from linguistic, archeological, and genetic sources suggests that the Transeurasian languages originated with millet cultivation and the early Amur gene pool in the West Liao River region. Millet farmers with Amur-related genes spread into contiguous regions across Northeast Asia during the Late Neolithic. Speakers of Proto-Transeurasian daughter branches admixed with Yellow River, western Eurasian, and Jomon populations over millennia, adding rice agriculture, western Eurasian crops, and pastoralist lifeways to the Transeurasian package.

“Taken alone, a single discipline cannot conclusively resolve the big questions surrounding language dispersal, but taken together, the three disciplines increase the credibility and validity of this scenario,” says Martine Robbeets, lead author of the study and leader of the Archaeolinguistic Research Group at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. “By aligning the evidence provided by the three disciplines, we gained a more balanced and rich understanding of Transeurasian migration than each of the three disciplines could provide us individually.”

The linguistic evidence for triangulation was derived from a new dataset of over 3,000 cognate sets representing over 250 concepts in nearly 100 Transeurasian languages. Researchers were able to construct a phylogenetic tree based on this data, which shows the roots of the Proto-Transeurasian family dating back 9,181 years to millet farmers living in the West Liao River region. The Farming Hypothesis is further supported by a small core of inherited words related to land cultivation, millets and millet agriculture, and other signs of a sedentary lifestyle.

The archaeological findings of the team also highlight the West Liao River basin, where communities began farming broomcorn millet around 9,000 years ago. A Bayesian analysis of 255 Neolithic and Bronze Age sites, including 269 directly carbon-dated cereals, revealed a cluster of related Neolithic cultures in the West Liao basin, from which two branches of millet-farming cultures separated: a Korean Chulmun branch and a branch of cultures covering the Amur, Primorye, and Liadong.

Analysis paired sites in the West Liao area with Mumun sites in Korea and Yayoi sites in Japan, demonstrating the addition of rice and wheat to the agricultural package in Liadong and Shangdong in the Early Bronze Age and their subsequent transmission to the Korean Peninsula and, from there, to Japan around 3,000 years ago.

The new study also includes the first collection of ancient genomes from Korea, the Ryukyu Islands, and early cereal farmers in Japan. By combining their findings with previously published East Asian genomes, the researchers discovered a genetic component known as “Amur-like ancestry” shared by all speakers of Transeurasian languages. They were also able to confirm that the Bronze Age Yayoi period in Japan saw a massive migration from the continent at the same time as farming was introduced.

The study’s findings show that, despite millennia of extensive cultural interaction, Transeurasian languages share a common ancestor and that agriculture was a driving force in the early spread of Transeurasian speakers.

“Accepting that the roots of one’s language – and, to a lesser extent, one’s culture – lie beyond present national boundaries can necessitate a kind of reorientation of identity, and this is not always an easy step for people to take,” Robbeets says. “However, human history science demonstrates that the history of all languages, cultures, and peoples is one of extensive interaction and mixture.”

The current study demonstrates how combining linguistic, archaeological, and genetic methods can improve the credibility and validity of a hypothesis, but the authors are quick to acknowledge the need for additional research. More ancient DNA, etymological research, and archaeobotanical research will deepen our understanding of Neolithic Northeast Asian human migrations and untangle the influence of later population movements, many of which were pastoralist in nature.

“There was far more to the creation of the Transeurasian language family as a whole than just one primary Neolithic pulse of migration,” says Mark Hudson, an archaeologist with the Archaeolinguistic Research Group. “There’s still a lot to learn.”