Antiquities made of stone, bones, or teeth give significant bits of knowledge into the means and techniques of early people, their way of behaving, and their culture. However, due to the fact that burials and grave goods were extremely uncommon in the Paleolithic, it has been challenging up until this point to identify specific individuals from these artifacts. This has made it harder to draw conclusions about things like the division of labor or the social roles that people played during this time.

An innovative, non-destructive method for DNA isolation from bones and teeth has been developed by an international, interdisciplinary research team led by the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig in order to directly link cultural objects to specific individuals and gain deeper insights into Paleolithic societies. The scientists focused specifically on skeletal artifacts because they are more porous and are therefore more likely to retain DNA that is present in skin cells, sweat, and other body fluids, despite the fact that they are generally less common than stone tools.

Another DNA extraction technique

Before the group could work with genuine curios, they originally needed to guarantee that the valuable items wouldn’t be harmed. ” Paleolithic tooth and bone artifacts’ surface structures reveal a lot about how they were made and used. According to Marie Soressi, an archaeologist from the University of Leiden who supervised the work alongside Matthias Meyer, a Max Planck geneticist, “preserving the integrity of the artifacts, including microstructures on their surface, was therefore a top priority.”

Elena Essel is working on the pierced deer tooth that was found in Denisova Cave in the clean laboratory. Credit: Max Planck

Foundation for Transformative Human Studies

The group tried the impact of different synthetic compounds on the superficial design of archeological bone and tooth pieces and fostered a non-disastrous phosphate-based technique for DNA extraction. ” “In our clean laboratory, one could say that we have developed a washing machine for ancient artifacts,” explains Elena Essel, the study’s lead author and the method’s creator. By washing the antiques at temperatures of up to 90°C, we can extricate DNA from the wash waters while safeguarding the ancient rarities.”

Early setbacks

The team first tried the method on a collection of artifacts from the French cave Quinçay dug from the 1970s to the 1990s. Even though DNA from the animals that made the artifacts could be identified in some cases, the majority of the DNA that was found came from people who handled the artifacts during or after excavation. Because of this, it was challenging to identify ancient human DNA.

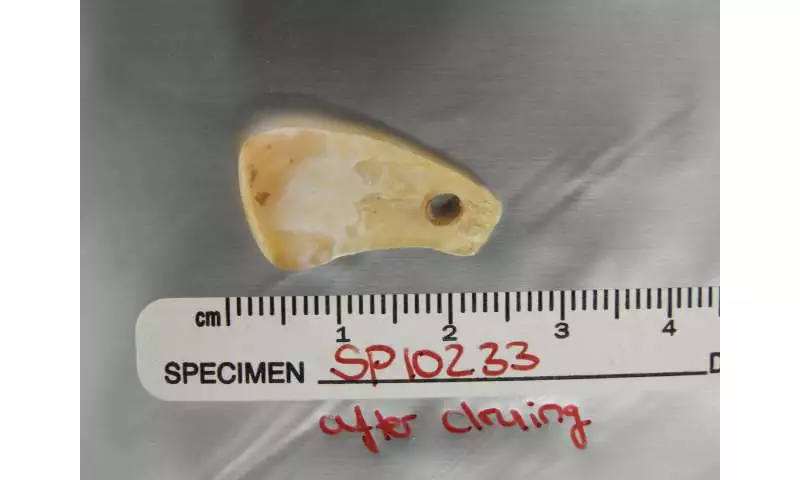

Prior to DNA extraction, the pierced deer tooth was discovered in Denisova Cave. Credit: The Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

Then focused on material that had been freshly excavated using gloves and face masks and placed in clean plastic bags with sediment still attached in order to overcome the issue of modern human contamination. The oldest reliably dated modern humans in Europe were found in Bulgaria’s Bacho Kiro Cave, and three tooth pendants from there showed significantly lower levels of modern DNA contamination. However, these samples did not contain any ancient human DNA.

The pierced deer tooth discovered from Denisova Cave after DNA extraction. Credit: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

A pendant from Denisova Cave

Archaeologists Maxim Kozlikin and Michael Shunkov, who were digging in Russia’s famous Denisova Cave, finally made the breakthrough possible. In 2019, ignorant of the new technique being created in Leipzig, they neatly exhumed and put away an Upper Paleolithic deer tooth pendant. The geneticists in Leipzig were able to extract not only the wapiti deer’s DNA but also a significant amount of ancient human DNA from it. “Almost as if we had sampled a human tooth,” says Elena Essel, “the amount of human DNA we recovered from the pendant was extraordinary.” Nature is the journal that published the findings.

Excavation works in the South Chamber of Denisova Cave in 2019. Credit: Sergey Zelensky

In light of the examination of mitochondrial DNA, the little piece of the genome that is solely acquired from the mother to their youngsters, the specialists reasoned that the vast majority of the DNA probably started from a single human person. Without sampling the precious object for C14 dating, they were able to estimate the pendant’s age at 19,000 to 25,000 years using the Wapiti and human mitochondrial genomes.

Notwithstanding mitochondrial DNA, the specialists likewise recovered a significant part of the atomic genome of its human proprietor. They determined that the pendant was made, used, or worn by a woman based on the number of X chromosomes. “The so-called “Ancient North Eurasians,” for whom skeletal remains have previously been analyzed, were also found to be genetically related to this woman from further east in Siberia.” “It is amazing that this is still possible after 20,000 years,” asserts Matthias Meyer. “Forensic scientists will not be surprised that human DNA can be isolated from an object that has been handled a lot.”

The researchers now hope to apply their method to a large number of other Stone Age objects made of bone and teeth in order to learn more about the sex and genetic ancestry of those who made, used, or wore them.

More information: Elena Essel, Ancient human DNA recovered from a Palaeolithic pendant, Nature (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06035-2. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06035-2