Due to its interactions with the human immune system, a drug approved in 2019 for the treatment of macular degeneration appeared to have caused uncommon retinal side effects, according to two new studies.

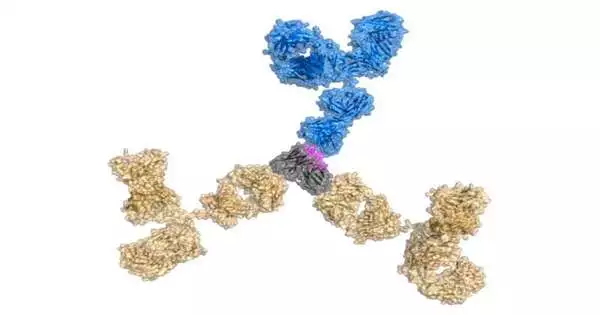

Brolucizumab, a monoclonal antibody, is a treatment for wet age-related macular degeneration, also known as AMD. It was created by the world’s largest pharmaceutical company, Novartis AG, in Switzerland. For those 65 and older, the condition is the main cause of vision loss. In addition to causing severe blurring, AMD is distinguished by a blind spot in the macula, the center of the retina. An excessive number of abnormal blood vessels that leak into the macula are a defining feature of the condition. To specifically target the harmful overgrowth, brolucizumab was created.

The drug is authorized in more than 70 countries, but despite pre-approval testing finding it to be safe, reports a few months after the drug’s introduction noted a small percentage of patients treated with the drug had rare retinal disorders. According to data published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, these side effects were estimated to have affected 21% of patients.

“In order to treat neovascular age-related macular degeneration, Novartis introduced brolucizumab in October 2019. Its single-chain variable fragment chemical targets vascular endothelial growth factor A.”

Anette C. Karle of the company’s biomedical research division in Basel.

To find out what went wrong, researchers at two Novartis research facilities launched investigations. The Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research in Basel, Switzerland, and Cambridge, Massachusetts, conducted these probes.

In one study, researchers looked at serum samples, and in another, they built models of the inflammatory conditions patients had. The study’s sole objective was to solve the puzzle of why some patients taking this medication started to experience retinal side effects while the vast majority of patients receiving the medication had no issues. It was conducted across two continents.

According to Anette C., “Novartis launched brolucizumab, a single-chain variable fragment molecule targeting vascular endothelial growth factor A, in October 2019 for the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Karle, who works for the business’ Basel-based biomedical research division.

One of the functions of the signaling protein known as vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) is to promote the growth of abnormal blood vessels. The choroid, a layer of the eye beneath the retina’s light-sensitive tissue, is where abnormal blood vessels grow, and this is what causes wet AMD. AMD causes vision loss due to blood vessel overgrowth.

Karle noted in a piece for Science Translational Medicine that patients who didn’t respond well to the medication developed noticeable eye conditions. According to Karle, lead author of one of the new studies, “In 2020, rare cases of retinal vasculitis and/or retinal vascular occlusion were reported frequently during the first few months after treatment initiation, consistent with a possible immunologic pathobiology.”.

The retina, the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye, has blood vessels that are affected by the inflammatory condition known as retinal vasculitis. The painless loss of vision is the most pernicious symptom of retinal vasculitis. The blockage of veins that carry blood away from the retina, on the other hand, results in retinal vascular occlusion. Edema, or the retention of fluid, can result from the blockage in the macula. There is a rapid and severe loss of visual acuity as a result of this trapped fluid accumulating beneath the retina as well as inside of it.

Retinal disorders were “inconsistent with preclinical studies in cynomolgus monkeys that demonstrated no drug-related intraocular inflammation, retinal vasculitis, or retinal occlusion, despite the presence of preexisting and treatment-emergent antidrug antibodies in some [test] animals,” according to Karle and colleagues’ research. A small percentage of patients in the clinical trial, though, developed the two inflammatory conditions after receiving brolucizumab treatment.

Karle and her colleagues compared serum samples from a few groups, including nonhuman primates, untreated healthy volunteers, and 28 patients from the clinical trials who developed retinal vasculitis or retinal vascular occlusion after receiving brolucizumab, in order to determine why the drug didn’t work for some patients.

Only patients with retinal vasculitis or retinal vascular occlusion exhibited potent T cell responses to the medication, according to serum analyses, indicating that both side effects required an immune response against brolucizumab. After taking the medication, the patients’ immune systems started attacking their retinas.

Dr. Jeffrey Kearns and colleagues used a translational approach in a second study, also published in Science Translational Medicine, to clarify how the body can unleash inflammatory forces following treatment with brolucizumab.

The Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Basel, Switzerland–based research team led by Kearns combined structural modeling, immunological analysis, and other methods to look into the underlying causes of retinal vasculitis and retinal vascular occlusion.

Kearns, a scientist at the Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research in Cambridge and the lead author of the second study, stated that the initial hypothesis that immune complexes could be important mediators was based on the discovery of antidrug antibodies in these patients. “Although the development of antidrug antibodies and immune complexes may be a prerequisite, other factors are probably involved in the minority of patients who develop retinal vasculitis or retinal vascular occlusion.”.

In a systems pharmacology model that replicated eye conditions, Kearns and his associates investigated the effects of brolucizumab. The model helped researchers pinpoint a number of variables that influenced how the treatment interacted with immune cells.

These included the drug’s linear epitope, which was shared by gut bacterial proteins, and the appearance after 13 weeks of non-native derivatives of brolucizumab. These symptoms caused immune complexes to form between brolucizumab and anti-drug antibodies.

In order to get more concrete answers, Karle, Kearns, and their colleagues advise more research. Both researchers acknowledge that their experiments were constrained by a scarcity of intraocular clinical samples and a lack of genetic risk factors and that additional, unidentified factors may be at work.

More information: Anette C. Karle et al, Anti-brolucizumab immune response as one prerequisite for rare retinal vasculitis/retinal vascular occlusion adverse events, Science Translational Medicine (2023). DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abq5241

Jeffrey D. Kearns et al, A root cause analysis to identify the mechanistic drivers of immunogenicity against the anti-VEGF biotherapeutic brolucizumab, Science Translational Medicine (2023). DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abq5068