The magnitude and exceptionality of the discovery, which is just 6 centimeters wide and 8 centimeters long, have left the European archaeological community in a state of shock. Members of OLEASTRO, a joint project between the Universities of Cordoba, Seville, and Montpellier, discovered it during prospecting in the municipality of Hornachuelos (Córdoba). in the municipality of Hornachuelos (Córdoba). It is a fragment of an oil amphora from the Roman region of Betica that was made approximately 1,800 years ago. It has written text on it.

Numerous pieces of ancient Rome-era pottery have been discovered, so the find would not have been unusual. The artificial mound made of Roman pottery known as Monte Testaccio in Rome is a wealth of information about the Roman wine and olive industries.

In fact, when the research team initially received the fragment, it did not particularly surprise them. Francisco Adame, a resident of the village of Ochavillo, was the first person to notice that sliver of Rome while walking through Arroyo de Tamujar, which is very close to the village of Villalón (Fuente Palmera).

The fact that the amphora had words on it was also not surprising to the research team because this is also quite common. In fact, archaeologists have been able to comprehend the Empire’s agricultural trade history thanks to the information printed on amphorae (producers, quantities, control, etc.).

Also, it wasn’t surprising to find a piece of an amphora in the Guadalquivir River plain, which was thought to be one of the main hubs for olive oil production and trade throughout the Empire. The remains of amphorae with “Betica” seals that have been preserved on Mount Testaccio demonstrate that a significant portion of the olive oil that Rome consumed was produced and packaged in the vicinity of Corduba, which is now known as modern-day Cordoba.

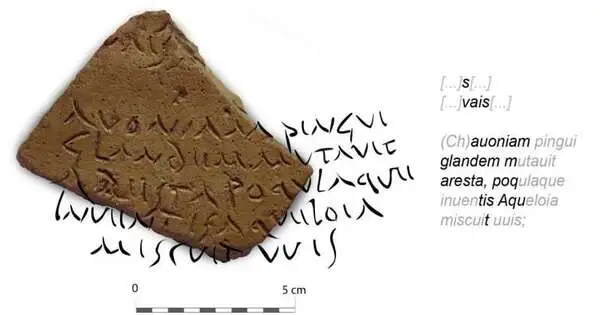

As a result, the text-covered amphora fragment initially appeared to be just another piece with no special significance. However, when the epigraph was deciphered, the following words emerged, altering everything:

Through overlaying, the researchers were able to infer that the text corresponds to the seventh and eighth verses of the first book of The Georgics, a poem by Virgil about farming and rural life written in 29 BC. These verses read,

Auoniam[pingui]glandem m[utauit]aresta, poq[ulaque][inuen]tisAqu[eloia][miscu]it [uuis]C[ambió] la bellota aonia por la espiga [fértil] [y mezcl]óel ag[ua] [con la uva descubierta]

For many generations, the Aeneid was taught in schools, and its verses were frequently written as a pedagogical exercise. As a result, they are frequently found on the remains of ceramic building materials. Numerous authors have hypothesized that these tablets served both educational and funeral purposes—Roman schoolchildren wrote Virgil on their chalkboards, and Virgil’s verses frequently served as an epitaph.

However, why not on an amphora? Why not the Aeneid instead of the Georgics? Since Virgil’s verses had never been recorded on an amphora intended for the oil trade, the project’s researchers realized that the tiny piece of pottery could be a one-of-a-kind and extremely valuable piece.

Dr. Iván González Tobar (Ph.D., University of Córdoba, currently a Juan de la Cierva researcher at the University of Barcelona and hired by the University of Montpellier when the piece was found) appears as principal investigator in the work, which was published in the Journal of Roman Archaeology (University of Cambridge). The main thesis of the work is that the verses were written on the underside of the amphora without anyone expecting to notice them.

Who composed it? The authors suggest a few possibilities here: that they were written by a factory specialist with a certain level of literacy or a villager related to the aristocratic family that owned the factory. They are also open to the possibility that a child worker wrote it because it has been documented that young workers are frequently employed at this kind of establishment.

In any case, Hornachuelos and Fuente Palmera’s verses on the amphora make it a one-of-a-kind work that raises numerous additional unanswered questions.

More information: Iván González Tobar et al, Las Geórgicas de Virgilio in figlinis: a propósito de un grafito ante cocturam sobre un ánfora olearia bética, Journal of Roman Archaeology (2023). DOI: 10.1017/S1047759423000156