A worldwide group of scientists has found a formerly obscure type of dinosaur in western Romania and named it after its area in Transylvania: Transylvanosaurus platycephalus lived quite a while ago and was an herbivore.

The news comes from the group led by scientist Felix Augustin at the College of Tübingen. The disclosure has quite recently been distributed in the Diary of Vertebrate Fossil Science. Other than Augustin, the review included researchers from the College of Bucharest and the College of Zurich.

Transylvanosaurus platycephalus in a real sense signifies “a level-headed reptile from Transylvania.” The beforehand obscure dinosaur was about two meters long, strolled on two legs, and had a place with the group of Rhabdodontidae. In Transylvania, they, like other neighborhood dinosaurs, just arrived at a small body size and are subsequently known as “bantam dinosaurs.”

“That’s not common. When we do find something, it is generally only a few bones; yet, even these can sometimes give great news—as is the case with Transylvanosaurus right now.”

Zoltán Csiki-Sava and his team from the University of Bucharest

The discovered Transylvanosaurus cranial bones add to our understanding of the evolution of European faunas prior to the extinction of dinosaurs a long time ago.”Probably a restricted stockpile of assets in these pieces of Europe around then prompted an adjustment in body size,” says Augustin.

For the greater part of the Cretaceous time frame, which endured from 145 million years ago to quite a while back, Europe was a tropical archipelago. Transylvanosaurus lived on one of the numerous islands along with other bantam dinosaurs, crocodiles, turtles, and goliath flying pterosaurs, which had wingspans of up to ten meters. “With each newfound species, we are negating the far-reaching suspicion that the Late Cretaceous fauna had a low variety in Europe,” says Augustin.

The Rhabdodontidae were the best-known group of small to medium-sized European herbivores during the Late Cretaceous.Related species recently found in a similar region had far smaller skulls than Transylvanosaurus. Then again, its closest family members lived in what is today France—this was a monstrous shock to the researchers. How did Transylvanosaurus find, as it would prefer, the “Island of the Bantam Dinosaurs” in what is currently Transylvania?

In the diary, scientists Felix Augustin, Zoltán Csiki-Sava from the College of Bucharest, Dylan Bastiaans from the College of Zurich/Naturalis Biodiversity Center Leiden, and free analyst Mihai Dumbravă from Dorset recreate different potential outcomes. The most established species seen as belonging to Rhabdodontidae come from Eastern Europe; the creatures might have spread westward from that point, and later certain species might have gotten back to Transylvania.

Changes in ocean level and structural cycles created transitory land spans between the numerous islands and might have urged these creatures to spread, the researchers guess. Moreover, it tends to be expected that practically all dinosaurs could swim to some degree, including Transylvanosaurus. “They had strong legs and a strong tail.” “Most species, specifically reptiles, can swim from birth,” says Augustin. Another chance is that different lines of rhabdodontid species created in Europe lined up in eastern and western Europe.

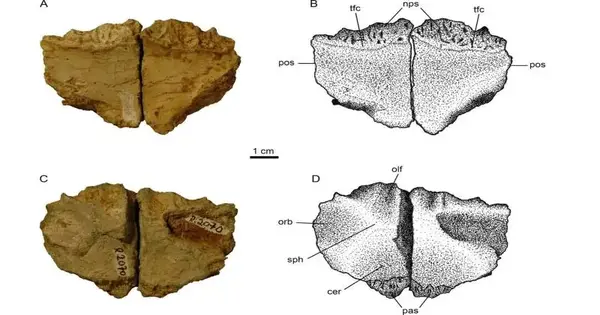

Exactly the way in which Transylvanosaurus wound up in the eastern piece of the European archipelago stays muddled for the present. “We have presently too little information within reach to respond to these inquiries,” says Augustin. For the ordered characterization, the group had two bones that were no longer than twelve centimeters in length: the back, lower part of the skull with the occipital foramen, and two front-facing bones.”Within the front-facing bone, it was even conceivable to perceive the shapes of the mind of Transylvanosaurus,” Bastiaans adds.

Zoltán Csiki-Sava and his group from the College of Bucharest found the skull bones of Transylvanosaurus in 2007 in a riverbed of the Haţeg Bowl in Transylvania. The Haţeg Bowl is one of the main spots for Late Cretaceous vertebrate disclosures in Europe. A total of ten dinosaur species have previously been distinguished there.

“That is surprising.” “At the point when we really do find something, there are in many cases a couple of bones; by and by, even these can once in a while yield astonishing news—for example, with Transylvanosaurus currently,” says Csiki-Sava. The bones of Transylvanosaurus had the option to make do for a huge number of years since they were safeguarded by the residue of an old riverbed—until another waterway washed them free once more.

“If the dinosaur had died and just lain on the ground instead of being halfway covered, climate and foragers would have annihilated its bones before long, and we would never have known about it,” Augustin says.

More information: Felix J. Augustin et al, A new ornithopod dinosaur, Transylvanosaurus platycephalus gen. et sp. nov. (Dinosauria: Ornithischia), from the Upper Cretaceous of the Haţeg Basin, Romania, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology (2022). DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2022.2133610

Journal information: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology