The present marine goliaths —, for example, blue and humpback whales — regularly make huge movements across the sea to raise and conceive an offspring in waters where hunters are scant, with many congregating a large number of years along the equivalent stretches of shore.

Presently, new exploration from a group of researchers — incorporating scientists with the College of Utah (Normal History Gallery of Utah and Branch of Geography and Geophysics), Smithsonian Foundation, Vanderbilt College, College of Nevada, Reno, College of Edinburgh, College of Texas at Austin, Vrije Universiteit Brussels, and College of Oxford — proposes that almost 200 million years before monster whales developed, school transport measured marine reptiles called ichthyosaurs might have been making comparable movements to raise and conceive an offspring together in relative security.

The discoveries, distributed today in the diary Current Science, look at a rich fossil bed in the famous Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park (BISP) in Nevada’s Humboldt-Toiyabe Public Woods, where numerous 50-foot-long ichthyosaurs (Shonisaurus popularis) lay froze in stone.

Co-wrote by Randall Irmis, NHMU boss keeper and guardian of fossil science, and academic partner, the review offers a conceivable clarification regarding how no less than 37 of these marine reptiles reached meet their closures in a similar territory — an inquiry that has vexed scientistss for the greater part 100 years.

“We show evidence that these ichthyosaurs died here in great numbers because they were travelling to this area to give birth for many generations throughout hundreds of thousands of years. That suggests that the behavior we see in whales today has been around for more than 200 million years.”

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History curator Nicholas Pyenson.

“We present proof that these ichthyosaurs passed on here in huge numbers since they were moving to this area to conceive an offspring for some ages across countless years,” said co-creator and Smithsonian Public Gallery of Normal History keeper Nicholas Pyenson. “That implies this sort of conduct we notice today in whales has been around for in excess of 200 million years.”

Throughout the long term, a few scientistss have suggested that BISP’s ichthyosaurs — hunters looking like curiously large stout dolphins which have been taken on as Nevada’s state fossil — passed on in a mass abandoning occasion, for example, those that occasionally besets current whales, or that the animals were harmed by poisons, for example, from a close by unsafe algal sprout. The issue is that these speculations need solid lines of logical proof to help them.

To attempt to settle this ancient secret, the group joined fresher paleontological methods, for example, 3D checking and geochemistry with customary paleontological constancy by poring over recorded materials, photos, maps, field notes and many drawers of gallery assortments for slivers of proof that could be reanalyzed.

Albeit most very much concentrated on paleontological locales exhume fossils so they can be more firmly concentrated by researchers at research foundations, the primary fascination for guests to the Nevada State Park-run BISP is an outbuilding like structure that houses what scientists call Quarry 2, a variety of ichthyosaurs that have been passed on implanted in the stone for people in general to see and appreciate. Quarry 2 has halfway skeletons from an expected seven individual ichthyosaurs that all seem to have passed on around a similar time.

“At the point when I previously visited the site in 2014, my most memorable idea was that the most ideal way to concentrate on it is make a full-variety, high-goal 3D model,” said lead creator Neil Kelley, an Associate Teacher at Vanderbilt College. “A 3D model would permit us to concentrate on how these huge fossils were organized comparable to each other without losing the capacity to go bone by bone.”

To do this, the exploration group teamed up with Jon Blundell, an individual from the Smithsonian Digitization Program Office’s 3D Program group, and Holly Little, informatics chief in the gallery’s Branch of Paleobiology.

While the scientistss were truly estimating bones and concentrating on the site utilizing customary paleontological methods, Little and Blundell utilized computerized cameras and a round laser scanner to take many photos and a huge number of point estimations that were then sewed together utilizing specific programming to make a 3D model of the fossil bed.

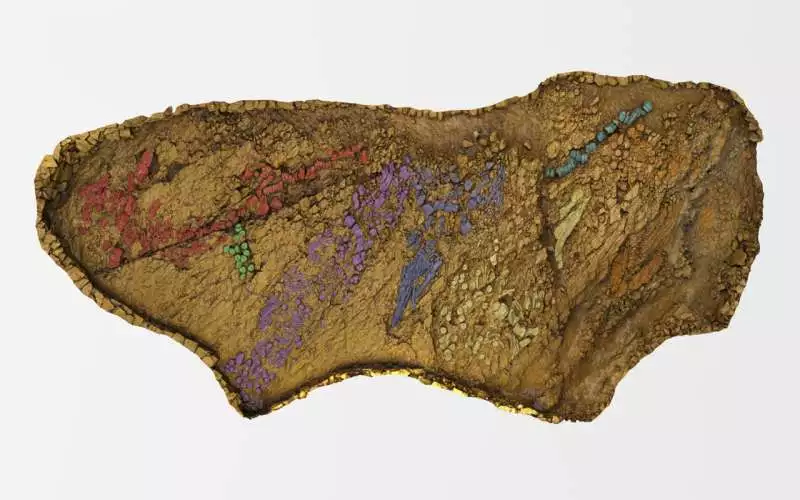

3D-model picture of the Shonisaurus popularis fossil bed at Quarry 2 in Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park, Nevada. Fossilized bones have been variety coded where each tone relates to an alternate skeleton.

“Our review joins both the land and natural aspects of fossil science to tackle this secret,” said Irmis. “For instance, we analyzed the compound make-up of the stones encompassing the fossils to decide if natural circumstances came about in so many Shonisaurus in one setting. When we decided it didn’t, we had the option to zero in on the conceivable natural reasons.”

The group gathered small examples of the stone encompassing the fossils and played out a progression of geochemical tests to search for indications of natural unsettling influence. One test estimated mercury, which frequently goes with huge scope volcanic action, and tracked down no altogether expanded levels.

Different tests analyzed various kinds of carbon and verified that there was no proof of unexpected expansions in natural matter in the marine silt that would bring about a lack of oxygen in the encompassing waters (however, similar to whales, the ichthyosaurs inhaled air).

These geochemical tests uncovered no signs that these ichthyosaurs died due to some disaster that would have truly upset the environment in which they passed on. The examination group kept on looking past Quarry 2 to the encompassing geography and every one of the fossils that had recently been exhumed from the area.

The geologic proof shows that when the ichthyosaurs passed on, their bones at last sank to the lower part of the ocean, instead of along a coastline sufficiently shallow to propose abandoning, precluding another speculation. Much really telling however, the region’s limestone and mudstone was packed with huge grown-up Shonisaurus examples, yet other marine vertebrates were scant. The heft of different fossils at BISP come from little spineless creatures like mollusks and ammonites (winding shelled family members of the present squid).

“There are such countless huge, grown-up skeletons from this one animal types at this site and barely anything else,” said Pyenson. “There are basically no remaining parts of things like fish or other marine reptiles for these ichthyosaurs to benefit from, and there are additionally no adolescent Shonisaurus skeletons.”

The scientists’ paleontological trawl had killed a portion of the likely reasons for death and began to give charming insights about the kind of environment these marine hunters were swimming in, yet the proof actually didn’t plainly highlight an elective clarification.

The exploration group found a vital piece of the riddle when they found small ichthyosaur stays among new fossils gathered at BISP and concealing inside more seasoned gallery assortments. Cautious correlation of the bones and teeth utilizing miniature CT X-beam checks at Vanderbilt College uncovered that these little bones were truth be told undeveloped and infant Shonisaurus.

“When obviously there was nothing for them to eat here, and there were huge grown-up Shonisaurusalong with incipient organisms and babies yet no adolescents, we began to truly consider whether this could have been a birthing ground,” said Kelley.

Complete tooth and halfway jaws (UMNH VP 32539) of the ichthyosaur Shonisaurus popularis from Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park, Nevada. These new fossils show that Shonisaurus was a dominant hunter at the highest point of its environment.

Further examination of the different layers in which the various groups of ichthyosaur bones were found likewise uncovered that the times of the numerous fossil beds of BISP were isolated by no less than countless years, in the event that not millions.

“Finding these various spots with similar species spread across geologic time with a similar segment design lets us know that this was a favored territory that these huge oceangoing hunters got back to for ages,” said Pyenson. “This is a reasonable natural sign, we contend, that this was a spot that Shonisaurus used to conceive an offspring, basically the same as the present whales. Presently we have proof that this kind of conduct is 230 million years of age.”

The group expressed the following stage for this line of exploration is to examine other ichthyosaur and Shonisaurus locales in North America in view of these new discoveries to start to reproduce their old world by maybe searching for other rearing destinations or for places with more prominent variety of different species that might have been rich taking care of reason for this wiped out dominant hunter.

“A thrilling aspect regarding this new work is that we found new examples of Shonisaurus popularis that have all around very much saved skull material,” Irmis said. “Joined with a portion of the skeletons that were gathered, harking back to the 1950s and 1960s that are at the Nevada State Gallery in Las Vegas, it’s probably we’ll ultimately have sufficient fossil material to at last precisely remake what a Shonisaurus skeleton resembled.”

The 3D sweeps of the website are currently accessible for different scientists to read up and for general society to investigate through the open-source Smithsonian’s Explorer stage, which is created and kept up with by Blundell’s colleagues at the Digitization Program Office, and anybody can take a more profound jump with the web-based 3D model.

“Our work is public,” said Blundell. “We aren’t simply checking locales and items and securing them. We make these sweeps to open up the assortment to different scientists and individuals from the public who can’t truly get to a gallery.”

More information: Neil P. Kelley, Grouping behavior in a Triassic marine apex predator, Current Biology (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2022.11.005. www.cell.com/current-biology/f … 0960-9822(22)01761-4

Online 3D model: 3d.si.edu/enter-sea-dragon