According to a study published in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Ariadna Nieto-Espinet and colleagues of the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas, Barcelona, livestock use was likely predominantly influenced by political organization and market demands in ancient European settlements.

The study of animal remains from archaeological sites, known as zooarchaeology, has the potential to reveal valuable information about previous human cultures. Livestock preferences in Europe are known to have evolved over time, but nothing is known about how much of this change is driven by the environmental, economic, or political situations of historical communities.

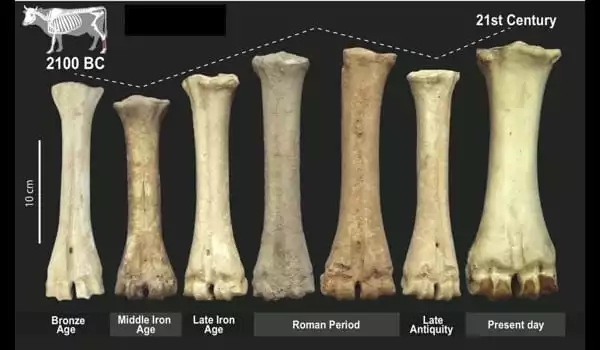

Nieto-Espinet and colleagues collected data from 101 archaeological sites in the northern Iberian Peninsula from the Late Bronze Age to Late Antiquity, a period of approximately 1700 years during which European culture and agricultural practices changed dramatically. They matched livestock remains to data on the local environment (including plant and climatic data) as well as the economic and political status of the settlement at each site.

We collected data from 101 archaeological sites in the northern Iberian Peninsula from the Late Bronze Age to Late Antiquity, a period of approximately 1700 years during which European culture and agricultural practices changed dramatically.

Nieto-Espinet

These findings indicate that political and economic considerations played a significant role in defining the species range and body size of prehistoric livestock. When governmental systems were more fragmented and food production was more centered on local markets throughout the Late Bronze Age and Late Antiquity, animal selection was more dependent on local environmental factors. However, during the later Iron Age and the Roman Empire, the demands of a pan-Mediterranean market economy supported additional changes in animal use that were not influenced by environmental conditions. As a result, zooarchaeology is an important source of information for understanding political and economic developments across time.

Southern Britain was captured by the Romans in the second half of the first century ad, becoming the Roman Empire’s northernmost stronghold. Despite its remote geographic location, the island’s incorporation into the Empire required a slew of significant socioeconomic and cultural changes. The significance, character, and distribution of such changes, as well as the survival and influence of Iron Age customs, have all been viewed and disputed differently by historians and archaeologists. Settlement patterns, ceramics, and iconography, for example, have been related to concerns of cultural and economic dominance, resistance, and syncretism, and have been the topic of extensive research.

However, until recently, the transition between the late Roman and early Anglo-Saxon periods received little study. This is due, in part, to a scarcity of non-urban sites demonstrating continuity of occupation between the fourth and fifth–sixth centuries ad; discontinuity is a topic frequently associated with the establishment of Anglo-Saxon communities and is often reflected in the material culture recovered from their settlements and cemeteries. Early Anglo-Saxon animal husbandry has primarily been studied in towns created after the collapse of Roman Britain. The site of West Stow, which dates from the fifth to eighth centuries, has received the most attention.

The data from these and other sites demonstrates a significant degree of heterogeneity in terms of representation of the key domesticates and their use, though the majority of assemblages differ significantly from those of the preceding Roman period. Such a lack of regional coherence during the early period of Anglo-Saxon establishment may indicate that the rural economy was not yet fully stabilized and integrated in the immediate aftermath of the Anglo-Saxons’ arrival. Rather, it appears that the nature of animal husbandry was determined by the demands of small, self-sufficient groups as well as environmental limits.

This research focuses on the transitions from the late Iron Age to the early Roman period, as well as the late Roman to the early Anglo-Saxon periods. It seeks to examine the nature and extent of change in the primary domesticates’ biometric characteristics and butchery. The interpretation of parallels and contrasts between assemblages dated to either end of these transitions will help to understand husbandry practices in Britain during the Roman era.