Another Dartmouth School drive-by review breaking down stone devices from southern China gives the earliest proof of rice collecting, dating to as far back as a long time ago. The analysts distinguished two strategies for reaping rice, which started with ricing training. The outcomes are distributed in PLOS ONE.

Wild rice differs from cultivated rice in that wild rice typically sheds ready-made seeds, breaking them to the ground as they mature, whereas developed rice seeds remain on the plants as they mature.

To collect rice, some kind of device would have been required. Early rice cultivators chose the seeds that remained on the plants when gathering rice with devices, so the extent of seeds that remained expanded continuously, resulting in taming.

“For a seriously prolonged stretch of time, one of the riddles has been that reaping devices have not been tracked down in that frame of mind from the early Neolithic time frame or New Stone Age (10,000–7,000 years prior to present)—the time span when we realized rice started to be trained,” says lead creator Jiajing Wang, an associate teacher of humanities at Dartmouth.

“In any case, when archeologists were working at a few early Neolithic destinations in the Lower Yangtze Stream Valley, they found a ton of little bits of stone, which had sharp edges that might have been utilized for gathering plants.”

“Because a rice plant contains several panicles that mature at different periods, the finger-knife harvesting technique was especially effective while rice domestication was in its early stages.”

Jiajing Wang, an assistant professor of anthropology at Dartmouth.

“Our speculation was that perhaps a portion of those little stone pieces were rice collecting devices, which is what our outcomes show.”

In the Lower Yangtze Stream Valley, the two earliest Neolithic culture bunches were the Shangshan and Kuahuqiao.

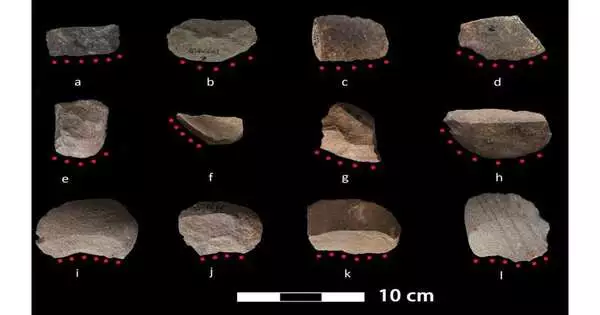

The analysts inspected 52 chipped stone apparatuses from the Shangshan and Hehuashan destinations, the last of which was involved with the Shangshan and Kuahuqiao societies.

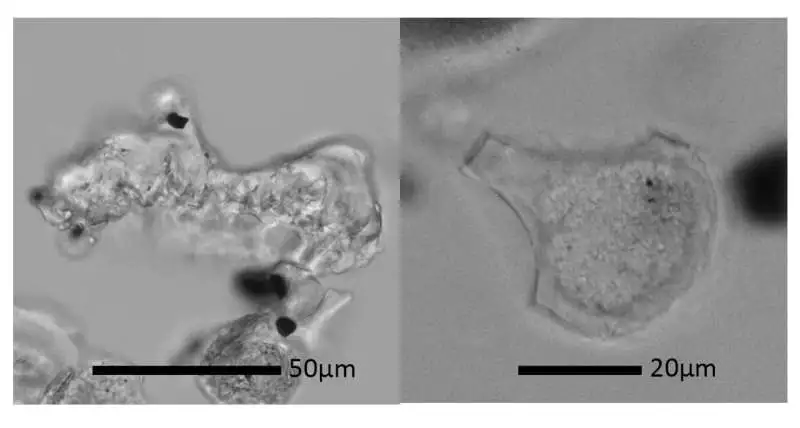

Phytolith recuperated from stone chips from Shanghsan and Hehuashan drops: rice husk phytolith (on left) and rice leaf phytolith.

The stone chips are unpleasant by all accounts and are not finely made; however, they have sharp edges. The chipped apparatuses are generally small enough to be held with one hand and are estimated to be around 1.7 crawls in width and length.

To decide whether the stone pieces were utilized for reaping rice, the group led use-wear and phytolith buildup investigations.

For the utilization wear examination, miniature scratches on the devices’ surfaces were inspected under a magnifying lens to decide how the stones were utilized. The outcomes showed that 30 pieces have wearable designs like those delivered by gathering siliceous (silica-rich) plants, probably including rice.

Fine striations, high finishes, and adjusted edges recognized the apparatuses that were utilized for cutting plants from those that were utilized for handling hard materials, cutting creature tissues, and scratching wood.

Through the phytolith buildup investigation, the specialists dissected the minuscule buildup left on the stone pieces known as “phytoliths” (silica skeletons of plants). They found that 28 of the devices contained rice phytoliths.

“What’s fascinating about rice phytoliths is that rice husks and leaves produce various types of phytoliths, which empowered us to decide how the rice was reaped,” says Wang.

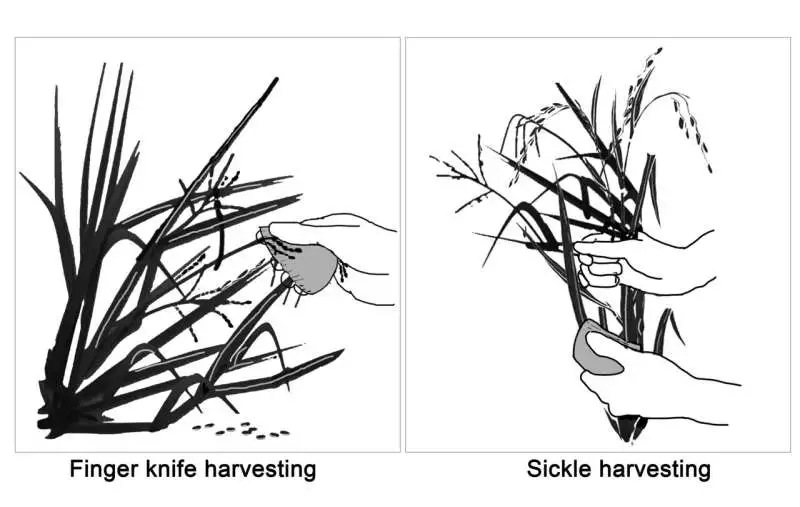

The discoveries from the utilization wear and phytolith examinations outlined that two sorts of rice collection strategies were utilized: “finger-blade” and “sickle” methods. The two strategies are not yet utilized in Asia today.

Schematic portrayal of rice-reaping techniques utilizing a finger-blade and sickle.

The stone chips from the beginning stage (10,000–8,200 BP) showed that rice was generally collected utilizing the finger-blade strategy, in which the panicles at the highest point of the rice plant are procured. The outcomes showed that the instruments utilized for finger-blade collecting had striations that were basically opposite or slanting to the edge of the stone chip, which proposes a cutting or scratching movement, and contained phytoliths from seeds or rice husk phytoliths, demonstrating that the rice was reaped from the highest point of the plant.

“Because a rice plant contains various panicles that develop at different times, the finger-blade reaping strategy is especially valuable when rice taming is in its early stages,” Wang says.

The stone pieces, be that as it may, from the later stage (8,000–7,000 BP) had more proof of a sickle harvest in which the lower portion of the plant was collected. These devices had striations that were prevalently lined up with the instrument’s edge, indicating that a cutting movement had likely been utilized.

“Sickle gathering was all the more widely utilized when rice turned out to be more tame and more ready seeds remained on the plant,” says Wang. “Since you are collecting the whole plant simultaneously, the rice leaves and stems could likewise be utilized for fuel, building materials, and different purposes, making this a significantly more successful gathering technique.”

According to Wang, “Both reaping strategies would have decreased seed breaking.” That is why we believe rice training was motivated by human oblivious determination.”

More information: Jiajing Wang et al, New evidence for rice harvesting in the early Neolithic Lower Yangtze River, China, PLOS ONE (2022). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0278200

Journal information: PLoS ONE