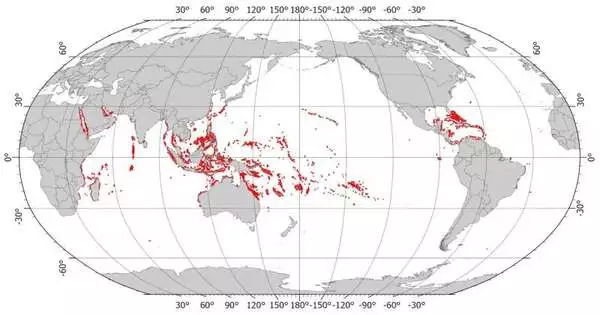

Coral reef islands and their reefs — found across the Indo-Pacific — normally develop and recoil because of perplexing natural and actual cycles that still can’t seem to be completely perceived. Presently, environmental change is upsetting them further, prompting new vulnerabilities for lawful sea zones and little island states.

Yet, it may not be an ideal opportunity to overreact yet. Various advances and new methodologies, combined with extended examination of coral reef island conduct, may assist in scattering a portion of the vulnerabilities and set claims.

A concentrate by College of Sydney scientists, distributed in Ecological Exploration Letters, shows that the standards for atolls and coral reefs in the global law of the ocean — currently dim and dependent upon translation because of their moving nature — will be under more prominent pressure as ocean levels rise and sea fermentation upsets reef honesty.

“A powerful coincidence is carrying shakiness and vulnerability to what are now troublesome limits to deciding with any incredible precision,” said Dr. Thomas Fellowes, a postdoctoral exploration partner at the School of Geosciences of the College of Sydney and lead creator of the paper.

“There are international results as well. Coral reef islands are the lawful reason for the majority of huge sea zones. Thus, the environmental disturbances we’re now seeing — and will find in the long time ahead — may have significant effects on little island states, yet in controversial limit debates in places like the South China Ocean.”

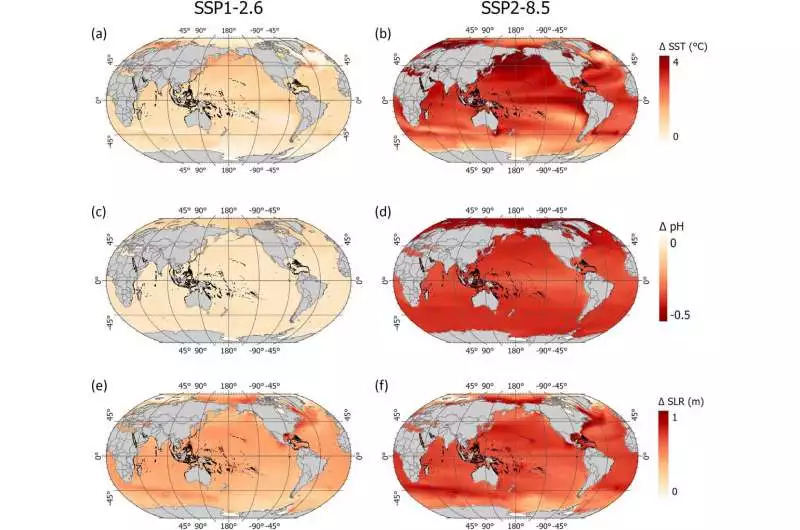

IPCC projections for 2081 to 2100 compared with 1995-2014 under the most ideal situation (1.5 C ascent, left) and assuming the worst (CO2 outflows twofold by 2050, right). Credit: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate ChangeThis agreement, endorsed by 167 countries, is widely regarded as governing everything from regional oceans (up to 12 nautical miles from a coast or the low-water line of a reef) to elite monetary zones (up to 200 nautical miles).It establishes the standards for route opportunities and enables countries to benefit from, save, and manage assets in adjacent waters.

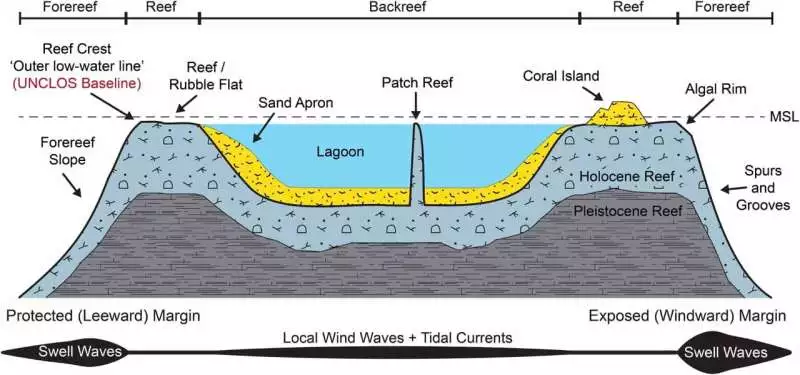

“For coral islands, the external ‘low-water line’ of the reef is utilized as the lawful gauge to lay out sea zones,” said Frances Anggadi, a Ph.D. understudy at the College of Sydney Graduate School. “The expected loss of sea zones because of changes in reef baselines from environmental change is a serious worry for countries like Kiribati, as well as bigger ones like Australia, who rely upon reefs and islands to keep up with their cases.”

Yet, there is still no reasonable arrangement on whether changes to the primary honesty of coral reef islands because of the environment will prompt lawful weaknesses.

“They may not, and that is the thing numerous Pacific island nations accept.” What’s reasonable is that a more itemized understanding of coral reef island conduct is required, alongside reexamining of the lawful standards.

That’s what Fellowes added, “Coral reefs are helpless, just flourishing inside a particular scope of biophysical, sea, and environmental conditions. Yet, changes in sedimentation because of environmental change might uphold coral islands and fortify a few sea claims. It’s not totally evident that there may be failures.”

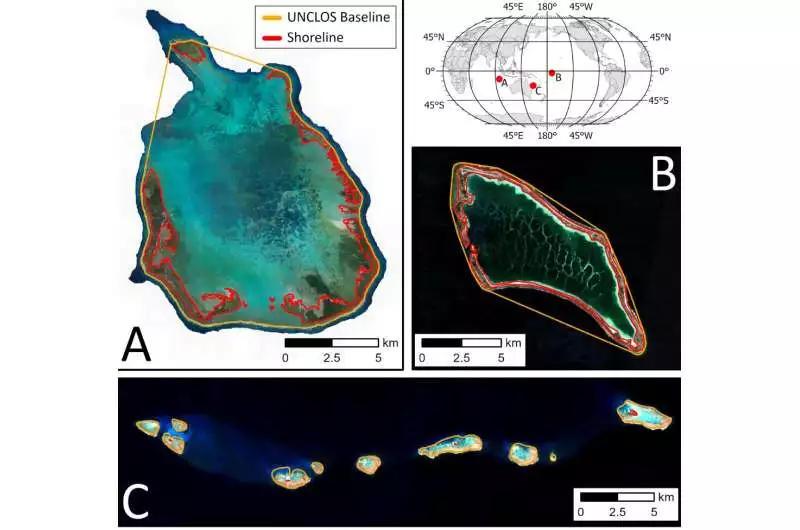

Coral reef island coastlines (red) and UNCLOS baselines (orange) at (a) Cocos Falling Island, Australia; (b) Kanton Reef, Kiribati; and (c) Wreck Reef, Australia. Credit: Geoscience Australia/Sentinel CenterThe analysts believe that characterizing reef baselines with geographic directions like GPS or remote detection approaches like satellite bathymetry is one way to bolster existing cases.

Another is to more readily comprehend what environmental change will mean for island tenability, since supporting human home or monetary life in an area is one more method for laying out a suitable case under the deal.

Yet, for these ways to deal with work, more information on every coral reef island framework is required to more precisely depict the genuine extent of existing cases, how strong those cases have been up to this point, and to more readily comprehend what parts of environmental change could influence them later on.

There are four ways in which environmental change is upsetting coral reef frameworks in ways that might influence sea limits: ocean level ascent, warming seas, sea fermentation, and expanded turbulence.

Each affects the interconnected biophysical processes that permit the creation, retreat, and generally primary security of coral reefs and islands.

Cross-part of coral reef geomorphic zones, showing wave energy slopes, sedimentary elements (islands, sand covers and tidal ponds) and UNCLOS baselines. For instance, higher temperatures trigger the removal of algal symbionts in corals and different spineless creatures (like monster mollusks), prompting coral dying, which — assuming an adequate number of coral living beings pass on — can bring about reef breakdown. In the long time ahead, this could prompt a shrinkage of the external low-water line of the reef, lessening the reason for a sea guarantee.

Seas ferment as they retain more carbon dioxide, reducing mineral immersion and making coral formation more difficult.Reef-building species such as Acropora — a small polyp found in tropical reefs — begin to change their skeletal designs to rely less on carbonate minerals, putting reef integrity at risk.

As the reefs develop and grow, they become either bordering, boundary, or atoll reefs. Bordering reefs are the most well-known, extending offshore from the shore, shaping lines along coastlines and encompassing islands. Boundary reefs do this at a more prominent distance, isolated from land by a tidal pond of frequently profound water. An atoll is formed when a volcanic island sinks beneath sea level and its reef coral continues to grow.

More information: Thomas E Fellowes et al, Stability of coral reef islands and associated legal maritime zones in a changing ocean, Environmental Research Letters (2022). DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/ac8a60

Journal information: Environmental Research Letters