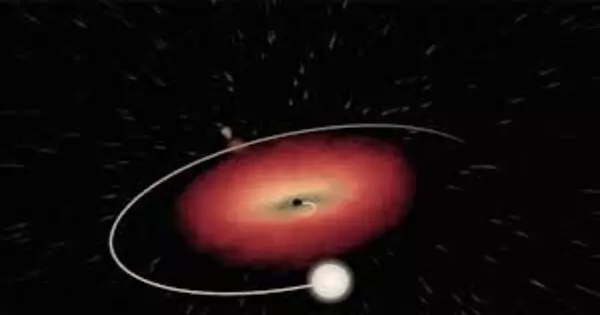

The blazing of a nearby star has attracted MIT space experts to a new and strange framework 3,000 light years away from Earth. The heavenly peculiarity seems, by all accounts, to be a new “dark widow twofold” — a rapidly turning neutron star, or pulsar, that is circumnavigating and gradually consuming a more modest buddy star, as its 8-legged creature namesake does to its mate.

Cosmologists know about around two dozen dark widow doubles in the Milky Way. This most up to date applicant, named ZTF J1406+1222, has the briefest orbital period yet recognized, with the pulsar and friend star circumnavigating each other at regular intervals. The framework is remarkable in that it seems to have a third, distant star that circles around the two internal stars like clockwork.

This probably triple dark widow is bringing up issues about how such a framework might have been shaped. In light of its perceptions, the MIT group proposes a history: As with most dark widow pairs, the triple framework probably emerged from a thick heavenly body of old stars known as a globular bunch. This specific bunch might have floated into the Milky Way’s middle, where the gravity of the focal dark opening was sufficient to pull the group apart while leaving the triple dark widow unblemished.

“In terms of black widows, this system is truly unique, since we discovered it with visible light, and because of its broad companion, and because it came from the galactic center. There’s still so much we don’t know about it. However, we now have a novel means of searching the sky for these systems.”

Kevin Burdge, a Pappalardo Postdoctoral Fellow in MIT’s Department of Physics.

“It’s a muddled birth situation,” says Kevin Burdge, a Pappalardo Postdoctoral Fellow in MIT’s Department of Physics. “This framework has most likely been drifting around in the Milky Way for longer than the sun has been up.”

Burdge is the creator of a review showing up in Nature that subtleties the group’s revelation. The scientists utilized another way to deal with identifying the triple framework. While most dark widow pairs are found through the gamma and X-beam radiation discharged by the focal pulsar, the group utilized apparent light, and specifically the glimmering from the double’s sidekick star, to identify ZTF J1406+1222.

“This framework is truly extraordinary to the extent that dark widows go, in light of the fact that we tracked down it with apparent light, and in view of its wide friend, and the reality that it came from the cosmic focus,” Burdge says. “There’s still a great deal we don’t comprehend about it.” “Be that as it may, we have a better approach for searching for these frameworks overhead.

The review’s co-creators are partners from different foundations, including the University of Warwick, Caltech, the University of Washington, McGill University, and the University of Maryland.

Constantly

Dark widow parallels are fueled by pulsars, quickly turning neutron stars that are the fallen centers of monstrous stars. Pulsars have a confounding rotational period, twirling around every couple of milliseconds and radiating blazes of high-energy gamma and X-beams simultaneously.

Ordinarily, pulsars turn down and bite the dust rapidly as they consume an enormous measure of energy. Be that as it may, from time to time, a passing star can give a pulsar new life. As a star approaches, the pulsar’s gravity pulls material off the star, which gives new energy to turn the pulsar back up. The “reused” pulsar then begins reradiating energy that further strips the star, and in the long run, annihilates it.

“These frameworks are called dark widows due to how the pulsar kind of consumes what it reuses, similarly as the bug eats its mate,” Burdge says.

Each dark widow paired to date has been identified through gamma and X-beam streaks from the pulsar. In a first, Burdge happened upon ZTF J1406+1222 through the optical blazing of the friend star.

It just so happens, the friend star’s day side—the side ceaselessly confronting the pulsar—can be more sizzling than its night side, because of the consistent high-energy radiation it gets from the pulsar.

“I thought, rather than gazing straight at the pulsar, have a go at searching for the star that it’s cooking,” Burdge makes sense of.

That’s what he contemplated, assuming space experts noticed a star whose brilliance was changing occasionally by a tremendous sum. It would be an area of strength for the star if it was paired with a pulsar.

Star movement

To test this hypothesis, Burdge and his associates glanced through optical information taken by the Zwicky Transient Facility, an observatory situated in California that takes wide-field pictures of the night sky. The group concentrated on the splendor of stars to see whether any were changing emphatically by a variable of at least 10, on a timescale of about an hour or less — signs that show the presence of a friendly star circling firmly around a pulsar.

The group had the option to select from the dozen known dark widow pairs, approving the new strategy’s precision. They then, at that point, detected a star whose splendor changed by an element of 13, at regular intervals, demonstrating that it was a possible piece of another dark widow twofold, which they named ZTF J1406+1222.

They looked at the star in perceptions taken by Gaia, a space telescope operated by the European Space Agency that keeps exact estimations of the position and movement of stars overhead. Thinking back through many years of old estimations of the star from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, the group observed that the parallel was being followed by another far off star. In light of their estimations, this third star gave off an impression of being circling the internal parallel at regular intervals.

Inquisitively, the stargazers have not straightforwardly identified gamma or X-beam emanations from the pulsar in the double, which is the common manner in which dark widows are affirmed. ZTF J1406+1222, consequently, is viewed as an applicant dark widow parallel, which the group desires to affirm with future perceptions.

“The one thing we know without a doubt is that we see a star with a day side that is a lot more sultry than the night side, circling around something at regular intervals,” Burdge says. “Everything appears to highlight it being a dark widow double. However, there are a couple of peculiar things about it, so it’s conceivable it’s something completely new. “

The group intends to keep noticing the new framework, as well as apply the optical method to enlighten more neutron stars and dark widows overhead.