Researchers discovered that high levels of an amino acid called homocysteine in the blood correlate strongly with the severity of an advanced form of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. They also discovered that vitamin B12 and folic acid could be used to prevent or postpone disease progression.

Scientists at Singapore’s Duke-NUS Medical School have discovered a mechanism that leads to an advanced form of fatty liver disease – and it turns out that vitamin B12 and folic acid supplements can reverse this process.

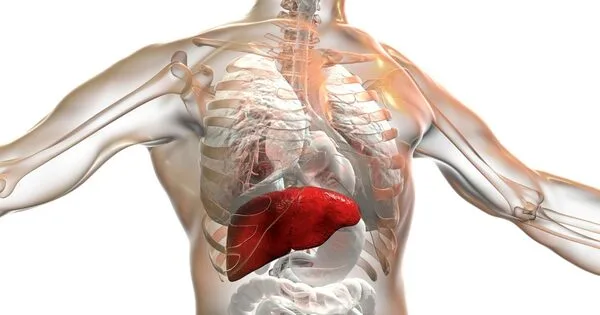

These findings could benefit people suffering from non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, a term that refers to a group of liver conditions that affect people who drink little to no alcohol and affects 25% of all adults worldwide and four in ten adults in Singapore.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is characterized by fat accumulation in the liver and is the leading cause of liver transplants worldwide. Its high prevalence is due to its link to diabetes and obesity, two major public health issues in Singapore and other developed countries. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis occurs when the condition progresses to inflammation and scar tissue formation (NASH).

Our findings are both exciting and significant because they suggest that a relatively cheap therapy, vitamin B12 and folic acid, could be used to prevent and/or delay the progression of NASH.

Dr Singh

“While fat deposition in the liver is reversible in its early stages, its progression to NASH causes liver dysfunction, cirrhosis, and increases the risk of liver cancer,” said Dr Madhulika Tripathi, first author of the study and senior research fellow at Duke-NUS’ Cardiovascular & Metabolic Programme.

Currently, there are no pharmacological treatments for NASH because scientists do not understand the disease’s mechanics. Although scientists knew that NASH is associated with elevated blood levels of an amino acid called homocysteine, they didn’t know what role, if any, it plays in the disorder’s development.

Dr. Tripathi, study co-author Dr. Brijesh Singh and their colleagues in Singapore, India, China, and the US confirmed the association of homocysteine with NASH progression in preclinical models and humans. They also found that, as homocysteine levels increased in the liver, the amino acid attached to various liver proteins, changing their structure and impeding their functioning.

In particular, when homocysteine attached to a protein called syntaxin 17, it blocked the protein from performing its role of transporting and digesting fat (known as autophagy, an essential cellular process by which cells remove malformed proteins or damaged organelles) in fatty acid metabolism, mitochondrial turnover, and inflammation prevention. This induced the development and progression of fatty liver disease to NASH.

Importantly, the researchers found that supplementing the diet in the preclinical models with vitamin B12 and folic acid increased the levels of syntaxin 17 in the liver and restored its role in autophagy. It also slowed NASH progression and reversed liver inflammation and fibrosis.

“Our findings are both exciting and significant because they suggest that a relatively cheap therapy, vitamin B12 and folic acid, could be used to prevent and/or delay the progression of NASH,” Dr Singh said. “In addition, serum and hepatic homocysteine levels may serve as a biomarker for the severity of NASH.”

Homocysteine may also affect other liver proteins, and the team hopes to find out what they are in the future. They are hopeful that additional research will result in the development of anti-NASH therapies.

Professor Paul M. Yen, Head of the Laboratory of Hormonal Regulation at Duke-NUS’ Cardiovascular & Metabolic Disorders Programme, and senior author of the study, said, “The potential for using vitamin B12 and folate, which have high safety profiles and are designated as dietary supplements by the US Food and Drug Administration, as first-line therapies for the prevention and treatment of NASH could result in tremendous cost savings and reduce the health burden from NASH in both developed and developing countries.”

According to Professor Patrick Casey, Senior Vice-Dean for Research at Duke-NUS, “At the moment, the only option for patients with end-stage liver disease is a transplant. Dr. Tripathi and her colleagues’ findings show that a simple, inexpensive, and easily accessible intervention could potentially halt or reverse liver damage, giving hope to those suffering from fatty liver disease. The findings of the team highlight the importance of basic scientific research, through which the scientific community continues to have a significant positive impact on the lives of patients.”