Gloomy feelings, tension, and sorrow are remembered to advance the beginning of neurodegenerative illnesses and dementia. Yet, what is their effect on the mind, and could their harmful impacts at any point be restricted?

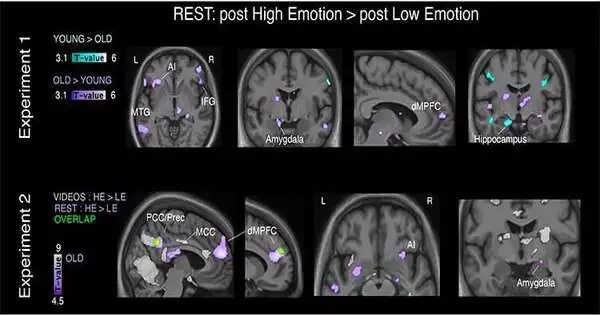

Neuroscientists at the University of Geneva (UNIGE) noticed the enactment of the minds of youthful and more seasoned adults when faced with the mental endurance of others. The neuronal associations of the more seasoned adults show huge, profound latency: gloomy feelings change them exorbitantly and over an extensive stretch of time, especially in the back cingulate cortex and the amygdala, two mind locales firmly engaged with the administration of feelings and personal memory.

These findings, published in Nature Aging, suggest that better management of these emotions—for example, through reflection—could help to limit neurodegeneration.

For more than 20 years, neuroscientists have been taking a gander at how the mind responds to feelings. “We are starting to comprehend what occurs right now in view of a profound boost,” makes sense to Dr. Olga Klimecki, a scientist at the UNIGE’s Swiss Place for Emotional Sciences and at the Deutsches Zentrum für Neurodegenerative Erkrankungen, who is the last creator of this study and did it as a feature of an European examination project coordinated by the UNIGE.

“Our goal was to identify what cerebral trace remained after seeing emotional events in order to assess the brain’s reaction and, more importantly, its healing mechanisms. We concentrated on older persons in order to distinguish between normal and abnormal aging.”

Patrik Vuilleumier, professor in the Department of Basic Neurosciences at the Faculty of Medicine

“In any case, what happens thereafter stays a secret.” How does the mind change, starting with one feeling and then moving on to the next? How can it get back to its underlying state? Does profound inconstancy change with age? What are the ramifications of the mind’s confusion of feelings?

Past examinations in brain science have shown that the capacity to change feelings rapidly is useful for emotional wellness. On the other hand, individuals who can’t direct their feelings and stay in a similar profound state for quite a while are at higher danger of gloom.

“Our point was to figure out what cerebral residue remained after the survey of profound scenes, to assess the mind’s response and, most importantly, its recuperation systems.” “We focused on more experienced adults to identify potential differences between typical and neurotic maturing,” says Patrik Vuilleumier, professor in the School of Medicine’s Branch of Essential Neurosciences and at the UNIGE’s Swiss Place for Emotional Sciences, who coordinated this work.

Not all minds are made equal.

The researchers showed short TV clips of people in extreme distress—for example, during a cataclysmic event or pain situation—along with recordings with unbiased close-to-home substance—to observe their mind activity using useful X-ray. In the first place, the group looked at a group of 27 people over the age of 65 and a group of 29 people over the age of 25.A similar trial was then rehashed with 127 more seasoned adults.

“More experienced individuals generally show a different example of mind action and network than more youthful individuals,” says Sebastian Baez Lugo, a scientist in Patrik Vuilleumier’s lab and the primary author of this work.

“This is especially observable in the degree of enactment of the default mode organization, a mind network that is profoundly enacted in the resting state.” Its actions are regularly upset by gloom or tension, suggesting that they are guided by feelings. In the more seasoned adults, part of this organization, the back cingulate cortex, which processes personal memory, shows an expansion in its associations with the amygdala, which processes significant and profound emotions. “These associations are more grounded in subjects with high tension scores, with rumination, or with negative contemplations.”

Sympathy and maturing

Nonetheless, more seasoned individuals will generally manage their feelings better than more youthful individuals and spotlight more effectively on good subtleties, in any event, during a pessimistic occasion. Yet, changes in the network between the cingulate cortex and the amygdala could demonstrate a deviation from the typical maturing peculiarity, emphasizing individuals who show more tension, rumination, and gloomy feelings.

The cingulate cortex is one of the areas generally impacted by dementia, suggesting that the presence of these side effects could increase the risk of neurodegenerative illness.

“Is it poor, profound guidance and tension that build the risk of dementia, or the reverse way around?” “We actually don’t have any idea,” says Sebastian Baez Lugo.

“Our theory is that more restless individuals would have no limit or a lower limit with regards to profound removal.” The system of profound latency in maturing would then be explained by the way these individuals’ minds remain “frozen” in a pessimistic state by relating the endurance of others to their own close-to-home recollections.”

Might reflection at any point be an answer?

Might it at any point be feasible to forestall dementia by following up on the system of profound latency? The research group is currently leading an 18-month interventional study to assess the effects of unknown dialect learning from one point of view and reflection practice from another.

“To further refine our findings, we will also investigate the effects of two types of reflection: care, which entails anchoring oneself in the present to focus on one’s own feelings, and what is known as “humane” contemplation, which intends to effectively increase positive feelings toward others,” the creators add.

This examination is essential for a huge European review, MEDIT-Maturing, which means to assess the effect of non-pharmacological mediations for better maturing.

More information: Sebastian Baez-Lugo et al, Exposure to negative socio-emotional events induces sustained alteration of resting-state brain networks in older adults, Nature Aging (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s43587-022-00341-6

Journal information: Nature Aging