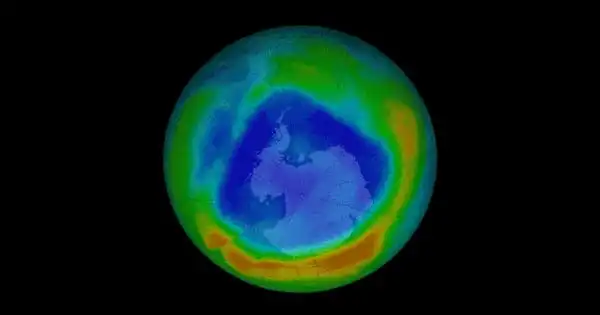

Increased UV radiation levels at the Earth’s surface are caused by ozone layer depletion, which is harmful to human health. Increases in certain types of skin cancer, eye cataracts, and immune deficiency problems are among the negative effects. Manufactured chemicals, particularly halocarbon refrigerants, solvents, propellants, and foam-blowing agents (chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), HCFCs, halons), are the primary causes of ozone depletion and the ozone hole (ODS).

According to new study led by the University of Bristol and Peking University, emissions of the ozone-destroying chemical dichloromethane from China have more than doubled over the previous decade. Since the adoption of the Montreal Protocol, there has been a remarkable decrease in emissions of the primary compounds responsible for depleting the stratospheric ozone layer, the component of the atmosphere that protects us from dangerous solar radiation.

In comparison to CFCs and other banned ozone-destroying substances, dichloromethane only lasts six months in the atmosphere. Because of this, its manufacture and usage have not been regulated by the Montreal Protocol in the same way that longer-lived ozone-depleting compounds have.

“International monitoring networks have known that global air concentrations of dichloromethane have been rising fast over the last decade,” said Dr. Luke Western of the University of Bristol’s School of Chemistry, “but until now, it was unclear what was driving the increase.”

If current levels of dichloromethane continue, we should expect a few years delay in ozone layer regeneration. However, if they continue to grow at the same rate as they have over the last decade, it might result in a delay of more than a decade, albeit future emissions are highly unclear.

Dr. Ryan Hossaini

To find an answer, experts from Peking University, the China Meteorological Administration, and the University of Bristol collaborated to investigate fresh data collected in China. Their findings were published in the journal Nature Communications today.

Minde An, a Peking University postgraduate student and visiting researcher at the University of Bristol, led the investigation. “China is a big producer and user of substances like dichloromethane,” he said. As a result, we sought to look at data from within the country to calculate its contribution to global emissions.

“According to our calculations, China’s contribution of total world emissions increased from around one-third to two-thirds during the last decade. Since 2011, worldwide emissions have increased at the same rate as Chinese emissions. We believe that dichloromethane emissions from China have increased as a result of its use as a solvent in numerous industrial applications and China’s burgeoning chloromethanes industry.”

In China, current restrictions on the use of dichloromethane are based solely on its toxicity or participation in the polluting of urban air. Dichloromethane levels in consumer products are regulated, and release rates from industrial processes are limited, but there is no limit on the total amount that can be discharged into the atmosphere.

Historically, dichloromethane emissions have been low enough that experts investigating ozone layer regeneration have not been concerned. However, the recent increase must be closely monitored in the future.

Dr. Ryan Hossaini, a co-author of the study from the University of Lancaster, stated: “If current levels of dichloromethane continue, we should expect a few years delay in ozone layer regeneration. However, if they continue to grow at the same rate as they have over the last decade, it might result in a delay of more than a decade, albeit future emissions are highly unclear.”

“The location of the emissions revealed in this investigation is significant. Short-lived chemicals, such as dichloromethane, are partially destroyed in the lower atmosphere before reaching the ozone layer. However, there are areas in Asia where the atmosphere can transport these compounds to the stratosphere very quickly. This means emissions from these regions may pack a bigger punch than those released elsewhere.”

Despite these fears, there are indicators that change is on the way. A draft regulation issued by China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment last month identified dichloromethane as a new contaminant whose usage in a variety of industries, including paint stripping and insulating foam production, might be prohibited.

Professor Matt Rigby, also of the University of Bristol’s School of Chemistry, expressed hope that these findings can be replicated in the future to assess the impact of regulatory modifications for dichloromethane and other substances of concern to the Montreal Protocol.

He continued, saying: “One of the most important outcomes of our work is that it demonstrates what can be accomplished via close collaboration among experts from all over the world. These Chinese measurements are extremely significant for ozone layer and climate researchers and policymakers. We look forward to continue this work in the future to give the Montreal Protocol parties with increasingly accurate information to help ensure that the ozone layer’s recovery remains on track.”