The critically endangered staghorn corals of Florida were surveyed to determine which ones can withstand future heatwaves in the ocean. The study’s findings assist organizations working to restore climate-resilient reefs in Florida and provide a blueprint for the success of restoration projects worldwide.

Florida’s critically endangered staghorn corals were surveyed in a first-of-its-kind study to determine which ones can withstand future heatwaves in the ocean. The study’s findings, led by scientists at Shedd Aquarium and the University of Miami’s (UM) Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, will benefit organizations working to restore climate-resilient reefs in Florida and provide a blueprint for the success of restoration projects worldwide.

“While this study was conducted in Florida, there is growing interest among scientists and managers in surveying heat tolerance in other coral populations around the world,” said Andrew Baker, professor and co-author of the study in the Department of Marine Biology and Ecology at the UM Rosenstiel School.

Our research serves as a model for other efforts to identify heat-tolerant corals, and it comes at a time when this knowledge can help transform approaches to halting coral decline due to climate change.

Andrew Baker

“Our research serves as a model for other efforts to identify heat-tolerant corals, and it comes at a time when this knowledge can help transform approaches to halting coral decline due to climate change. Heat tolerance population censuses are useful not only for scientists trying to understand how and why corals vary in their thermal tolerance, but also for managers and policymakers guiding the future of reef restoration.”

The new study, which was published today in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, may aid in optimizing the human interventions required to help corals survive the effects of climate change.

The research was carried out over two research expeditions in 2020, during which a team used Shedd’s research vessel, the R/V Coral Reef II, to test the heat tolerance of 229 different strains of staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis) that are actively propagated by South Florida’s coral restoration programs, which span Broward County to the lower Florida Keys and are run by Nova Southeastern University, Mote Marine Laboratory, and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

The team used a set of custom-built portable stress tanks to expose fragments of each coral to different temperatures and measure how much heat stress each coral could withstand before showing the same amount of bleaching, the heat stress response in which corals expel the vital symbiotic algae that live within them, before showing the same amount of bleaching. Heat tolerance genetic factors were also investigated using DNA samples. The findings revealed significant variation in the heat tolerance of the 229 corals studied, with some strains showing higher heat tolerance, which could mean better survival in warming oceans.

The study’s lead author, Ross Cunning, a research biologist at Shedd Aquarium and alumnus of the UM Rosenstiel School, said, “Coral reef decline due to climate change is accelerating worldwide, but active reef restoration efforts, which offer the best chance to boost the resilience of reefs through challenging future environments, are accelerating as well. However, in order for future reefs to survive in warmer oceans, restoration and other conservation interventions must be optimized with heat tolerance in mind. We conducted the first large-scale census of coral heat tolerance in this study to identify thermotolerant individuals that can be used for various restoration techniques right away.”

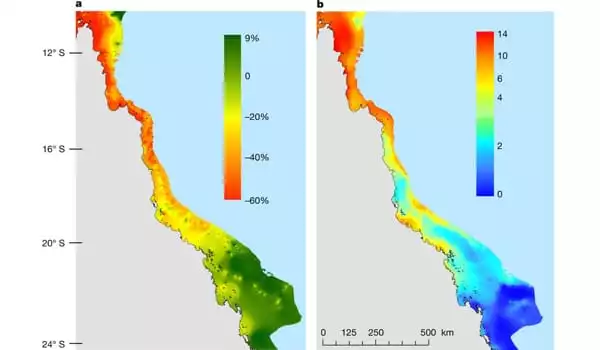

Coral propagation and outplanting, a process in which scientists grow coral fragments in nurseries and then transfer them to reefs, is one restoration approach that can benefit from the study’s findings. More resistant corals could be propagated and transferred to shallow or near-shore reefs that are more likely to experience high temperatures, while more sensitive fragments could be placed on deeper, offshore reefs that are less likely to heat up, according to this method.

As more of these heat-tolerant corals are outplanted to reefs, they will help to increase the climate-resilience of natural populations by increasing the heat tolerance of the next generation of corals. Other applications of the research include speeding up natural processes by selectively breeding high-performing corals to produce heat-resistant offspring, as well as transporting thermotolerant corals from thriving reefs to dying reefs.

Coral reefs are biodiversity hotspots that protect coastal economies and provide essential animal protein to human populations all over the world. Staghorn corals were once common on Caribbean shallow reefs, but have been decimated across their range since the early 1980s, making them a focal species for restoration efforts across the region, including in Florida. Restoration practitioners propagate and outplant tens of thousands of staghorn coral fragments onto Florida’s reefs each year, making Florida’s staghorn corals the world’s largest single-species coral restoration program.