Jimmy Jiang imagines a future where each house is controlled by environmentally friendly power stored in batteries—maybe even those he and his understudies are planning today.

In his science lab, Jiang and his understudies at the College of Cincinnati have made another battery that could have significant ramifications for the huge energy capacity required by wind and solar-based ranches.

Advancements, for example, in UCs will significantly affect efficient power generation, Jiang said. Batteries store environmentally friendly power for when it’s required, not when it’s created. This is essential for benefiting from wind and sun-based power, he said.

“Energy age and energy utilization are constantly befuddled,” he said. “That is the reason it’s vital to have a gadget that can store that energy for a brief time and deliver it when it’s required.”

“Membranes are super expensive, We developed a new type of energy storage material that improves performance at a lower cost.”

Jiang, an associate professor in UC’s College of Arts and Sciences.

They portrayed their clever plan in the diary Nature Correspondences.

Customary vehicle batteries contain a blend of sulfuric acid, corrosive chemicals, and water. And keeping in mind that they are cheap and produced using readily accessible materials, they have extreme downsides for modern or huge-scale use. They have an exceptionally low energy thickness, which isn’t helpful for putting away the megawatts of force expected to drive a city.

What’s more, they have a low limit for electrochemical dependability. Jiang said that implies they can explode.

“Water has a voltage limit. When the voltage of a fluid battery surpasses the soundness window of 1.5 volts, the water can disintegrate or be separated into hydrogen and oxygen, which is touchy,” he said.

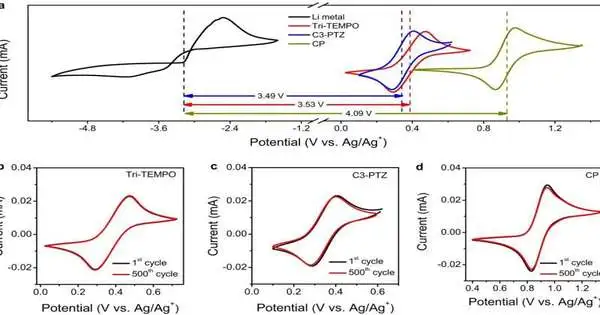

However, Jiang and his understudies have fostered a battery without water that can produce almost 4 volts of force. Jiang’s clever plan does as such without a film separator, which is among the priciest pieces of these sorts of batteries, he said.

“Layers are really costly,” said Jiang, an academic administrator in UC’s School of Expressions and Sciences. “We fostered another sort of energy stockpiling material that further develops execution at a lower cost.”

Moreover, films are wasteful, he said.

“They can’t separate the positive and negative sides totally, so there is generally hybridity,” he said.

The gathering has submitted temporary patent applications, he said.

“There is still far to go,” Jiang said.

In any case, he said we are tearing toward a battery upset in the following 20 years.

“I’m sure about that. There is a great deal of serious exploration going into pushing the limits of battery execution,” he said.

His understudies are similarly energetic. Doctoral understudy and study co-creator Rabin Siwakoti said the battery offers higher energy thickness.

“So even a little battery can give you more energy,” he said.

“We’ve figured out how to take out the film from a battery, which is a colossal part of forthright expenses. It’s essentially as much as 30% of the expense of the battery,” co-creator and doctoral understudy Jack McGrath said.

Co-creator Soumalya Sinha, a meeting teacher at UC, said nations are hustling to foster less expensive, more productive batteries.

“This plan altogether diminishes material expenses,” he said. “We’re attempting to accomplish a similar exhibition at a less expensive expense.”

More information: Rajeev K. Gautam et al, Development of high-voltage and high-energy membrane-free nonaqueous lithium-based organic redox flow batteries, Nature Communications (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-40374-y