There’s a new nanomaterial on the block. A college of Oregon’s scientific experts have figured out how to make carbon-based particles with a one-of-a kind underlying element: interlocking rings.

Like other nanomaterials, these connected particles have intriguing properties that can be “tuned” by changing their size and composition. That makes them possibly valuable for a variety of uses, like specific sensors and new sorts of hardware.

“It’s another geography for carbon nanomaterials, and we’re finding new properties that we haven’t had the option to see previously,” said James May, an alumni understudy in science teacher Ramesh Jasti’s lab and the main author on the paper. May and his partners report their discoveries in a paper distributed in Nature Science.

“It’s a new architecture for carbon nanomaterials, and we’re discovering new features that we hadn’t seen before,”

James May, a graduate student in chemistry professor Ramesh Jasti’s lab

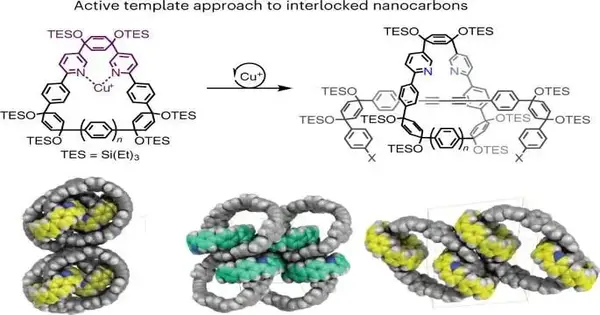

However, different labs have additionally combined different kinds of interlocking particles; the Jasti lab’s strategy permits carbon nanotube-like designs to be connected together. It will permit scientific experts to make various minor departures from the design and all the more completely investigate the properties of the new materials.

“You can make structures that you can’t with different techniques,” Jasti said.

For instance, his group utilized the way to deal with three interlocked rings as well as a bar-like construction with numerous rings that can slide all over. The development outgrew Jasti’s work on nanohoops, which are rings of carbon iotas that are a pared-back variety of long, thin carbon nanotubes.

“Since we’re ready to make these roundabout designs voluntarily, I began thinking: might you at some point make things that simply don’t exist in nature?” Jasti said. “That is where this thought of interlocking rings came in.”

Finding a progression of synthetic responses that could produce the muddled ring structures was an inventive strategy. Their answer relies on adding a decisively positioned metal particle to one ring. That metal launches the synthetic response to make the subsequent ring, constraining it to occur inside the principal ring. When that response occurs, the subsequent ring is caught and locked along with the main ring.

“We’re ready to get science to occur within a space where it very well may never happen,” May said.

If the size of the interlocked atoms changes, or if the rings are organized differently, or if different synthetic components are mixed in with the general mishmash, the interlocked atoms behave differently.By making nanoscale changes, researchers could improve the material to do precisely what they maintain that it should do. Since the class of materials is so new, researchers are still sorting out the potential outcomes as a whole.

However, Jasti’s group is especially keen on their true capacity as sensors, where an adjustment of the place of the rings because of a specific substance could prompt a fluorescent shine.

They could also be used to create adaptable devices or dynamic biomedical materials.

“Common carbon nanomaterials like carbon nanotubes, graphene, or even precious stones are static materials,” he said. “Here, we have made new kinds of carbon nanomaterials that keep up with their captivating electrical and optical properties yet presently have the ability to do things like turn, pack, or stretch.”

More information: James H. May et al, Active template strategy for the preparation of π-conjugated interlocked nanocarbons, Nature Chemistry (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41557-022-01106-9

Journal information: Nature Chemistry